Persian Empire

2000-1800 BC, Aryan migration from Southern Russia to Near East

Persia's earliest known kingdom was the proto-Elamite Empire followed by

The Medes

Deioces, 728BC - 675BC

Phraortes (Kashtariti?), 675BC - 653BC

Scythian interregnum

Cyaxares, 625BC - 585BC

Astyages, 585BC - 550BC

628 BC, Birth of Zartosht, Zoroaster, the Persian Prophet

Achaemenid Dynasty

Achaemenes

Teispes

Cyrus I

Cambyses I (Kambiz)

Cyrus the Great, Start of Achaemenid Empire, 559BC -530BC

Kambiz II, 530BC - 522BC

Smerdis (the Magian), 522BC

Darius I the Great, 522BC - 486BC

Xerxes I (Khashyar), 486BC - 465BC

Artaxerxes I , 465BC - 425BC

Xerxes II, 425BC - 424BC (45 days)

Darius II, 423BC - 404BC

Artaxerxes II, 404BC - 359BC

Artaxerxes III, 359BC - 339BC

Arses, 338BC - 336BC

Darius III, 336BC - 330BC

Hellenistic Period

Alexander (III), 330BC - 323BC

Philip III (Arrhidaeus), 323BC - 317BC

Alexander IV, 317BC - 312BC

Seleucids

Seleucus I, 312BC - 281BC

Antiochus I Soter, 281BC - 261BC (coregent)

Seleucus, 280BC - 267BC (coregent)

Antiochus II Theos, 261BC - 246BC

Sleucus II Callinicus, 246BC - 238BC

The early history of man in Iran goes back well beyond the Neolithic period, it begins to get more interesting around 6000 BC, when people began to domesticate animals and plant wheat and barley. The number of settled communities increased, particularly in the eastern Zagros mountains, and handmade painted pottery appears. Throughout the prehistoric period, from the middle of the sixth millennium BC to about 3000 BC, painted pottery is a characteristic feature of many sites in Iran.

The Persian Empire is the name used to refer to a number of historic dynasties that have ruled the country of Persia (Iran). Persia's earliest known kingdom was the proto-Elamite Empire, followed by the Medes; but it is the Achaemenid Empire that emerged under Cyrus the Great that is usually the earliest to be called "Persian." Successive states in Iran before 1935 are collectively called the Persian Empire by Western historians.

The name 'Persia' has long been used by the West to describe the nation of Iran, its people, or its ancient empire. It derives from the ancient Greek name for Iran, Persis. This in turn comes from a province in the south of Iran, called Fars in the modern Persian language and Pars in Middle Persian. Persis is the Hellenized form of Pars, based on which other European nations termed the area Persia. This province was the core of the original Persian Empire. Westerners referred to the state as Persia until March 21, 1935, when Reza Shah Pahlavi formally asked the international community to call the country by its native name. Some Persian scholars protested this decision because changing the name separated the country from its past. It also caused some Westerners to confuse Iran with Iraq; so in 1959 his son Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi announced that both Persia and Iran can be used interchangeably.

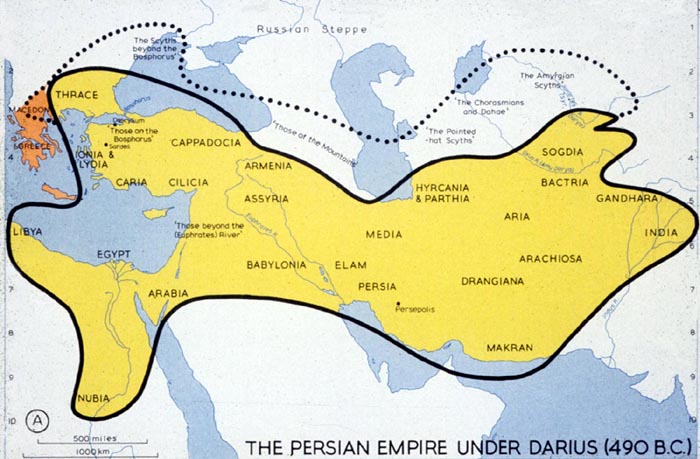

The Persian Empire dominated Mesopotamia from 612-330 BC. The Achaemenid Persians of central Iran ruled an empire which comprised Iran, Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, and parts of Asia Minor and India. Their ceremonial capital was Persepolis in southern Iran founded by King Darius the Great. Persepolis was burned by Alexander the Great in 331 B.C. Only the columns, stairways, and door jambs of its great palaces survived the fire. The stairways, adorned with reliefs representing the king, his court, and delegates of his empire bringing gifts, demonstrate the might of the Persian monarch.

The first record of the Persians comes from an Assyrian inscription from c. 844 BC that calls them the Parsu (Parsuash, Parsumash) and mentions them in the region of Lake Urmia alongside another group, the Madai (Medes). For the next two centuries, the Persians and Medes were at times tributary to the Assyrians. The region of Parsuash was annexed by Sargon of Assyria around 719 BC. Eventually the Medes came to rule an independent Median Empire, and the Persians were subject to them.

The Achaemenids were the first line of Persian rulers, founded by Achaemenes (Hakaimanish), chieftain of the Persians around 700 BC.

Around 653 BC, the Medes came under the domination of the Scythians, and the son of Achaemenes, a certain Teispes, seems to have led the nomadic Persians to settle in southern Iran around this time -- eventually establishing the first organized Persian state in the important region of Anshan as the Elamite kingdom was permanently destroyed by the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal (640 BC).

The kingdom of Anshan and its successors continued to use Elamite as an official language for quite some time after this, although the new dynasts spoke Persian, an Indo-Iranian tongue.

Teispes' descendants branched off into two lines, one line ruling in Anshan, while the other ruled the rest of Persia. Cyrus II the Great united the separate kingdoms around 559 BC.

Cyrus the Great (559-529 BC)

"I am Cyrus, who founded the empire of the Persians.

Grudge me not therefore, this little earth that covers my body."

At this time, the Persians were still tributary to the Median Empire ruled by Astyages.

Cyrus rallied the Persians together, and in 550 BC defeated the forces of Astyages, who was then captured by his own nobles and turned over to the triumphant Cyrus, now Shah of the Persian kingdom.

As Persia assumed control over the rest of Media and their large Middle Eastern empire, Cyrus led the united Medes and Persians to still more conquest. He took Lydia in Asia Minor, and carried his arms eastward into central Asia.

Finally in 539 BC, Cyrus marched triumphantly into the ancient city of Babylon. After this victory, he set the standard of the benevolent conqueror by issuing the Cyrus Cylinder. In this declaration, the king promised not to terrorize Babylon nor destroy its institutions and culture.

- The Cyrus Cylinder is an artifact of the Persian Empire, consisting of a declaration inscribed on a clay barrel. Upon his taking of Babylon, Cyrus the Great issued the declaration, containing an account of his victories and merciful acts, as well as a documentation of his royal lineage. It was discovered in 1879 in Babylon, and today is kept in the British Museum.

The royal history given on the cylinder is as follows: The founder of the dynasty was King Achaemenes (ca. 700 BC) who was succeeded by his son Teispes of Anshan. Inscriptions indicate that when the latter died, two of his sons shared the throne as Cyrus I of Anshan and Ariaramnes of Persia. They were succeeded by their respective sons Cambyses I of Anshan and Arsames of Persia. Cambyses is considered by Herodotus and Ctesias to be of humble origin. But they also consider him as being married to Princess Mandane of Media, a daughter of Astyages, King of the Medes and Princess Aryenis of Lydia. Cyrus II was the result of this union.

Cyrus was killed during a battle against the Massagetae or Sakas.

Cyrus' son, Cambyses II, was next in line to rule. When Cyrus conquered Babylon in 539 BC he was employed in leading religious ceremonies (Chronicle of Nabonidus), and in the cylinder which contains Cyrus's proclamation to the Babylonians his name is joined to that of his father in the prayers to Marduk. On a tablet dated from the first year of Cyrus, Cambyses is called king of Babel. But his authority seems to have been quite ephemeral; it was only in 530 BC, when Cyrus set out on his last expedition into the East, that he associated Cambyses on the throne, and numerous Babylonian tablets of this time are dated from the accession and the first year of Cambyses, when Cyrus was "king of the countries" (i.e. of the world). After the death of his father in the spring of 528 BC, Cambyses became sole king. The tablets dated from his reign in Babylonia run to the end of his eighth year, i.e. March 521 BC. Herodotus (3. 66), who dates his reign from the death of Cyrus, gives him seven years five months, i.e. from 528 to the summer of 521.

It was quite natural that, after Cyrus had conquered Asia, Cambyses should undertake the conquest of Egypt, the only remaining independent state of the Eastern world.

Before he set out on his expedition he killed his brother Bardiya (Smerdis), whom Cyrus had appointed governor of the eastern provinces. The date is given by Darius, whereas the Greek authors narrate the murder after the conquest of Egypt. The war took place in 525, when Amasis had just been succeeded by his son Psammetichus III. Cambyses had prepared for the march through the desert by an alliance with Arabian chieftains, who brought a large supply of water to the stations.

King Amasis had hoped that Egypt would be able to withstand the threatened Persian attack by an alliance with the Greeks.But this hope failed the Cypriot towns and the tyrant Polycrates of Samos, who possessed a large fleet, now preferred to join the Persians, and the commander of the Greek troops, Phanes of Halicarnassus, went over to them. In the decisive battle at Pelusium the Egyptians were beaten, and shortly afterwards Memphis was taken. The captive king Psammetichus was executed, having attempted a rebellion. The Egyptian inscriptions show that Cambyses officially adopted the titles and the costume of the Pharaohs, although we may very well believe that he did not conceal his contempt for the customs and the religion of the Egyptians.

From Egypt Cambyses attempted the conquest of Kush, i.e. the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe, located in the modern Sudan. But his army was not able to cross the deserts after heavy losses he was forced to return. In an inscription from Napata (in the Berlin museum) the Nubian king Nastesen relates that he had beaten the troops of Kembasuden, i.e. Cambyses, and taken all his ships (H. Schafer, Die Aethiopische Königsinschrift des Berliner Museums, 1901).

Another expedition against the Siwa Oasis failed likewise, and the plan of attacking Carthage was frustrated by the refusal of the Phoenicians to operate against their kindred.

Death of Cambyses

Meanwhile in Persia a usurper, the Magian Gaumata, arose in the spring of 522, who pretended to be the murdered Bardiya (Smerdis) and was acknowledged throughout Asia. Cambyses attempted to march against him, but, seeing probably that success was impossible, died by his own hand (March 521). This is the account of Darius, which certainly must be preferred to the traditions of Herodotus and Ctesias, which ascribe his death to an accident. According to Herodotus (3.64) he died in the Syrian Ecbatana, i.e. Hamath; Josephus (Antiquites xi. 2. 2) names Damascus; Ctesias, Babylon, which is absolutely impossible.

According to Herodotus, Cambyses sent an army to threaten the Oracle of Amun at the Siwa Oasis. The army of 50,000 men was halfway across the desert when a massive sandstorm sprung up, burying them all. Although many Egyptologists regard the story as a myth, people have searched for the remains of the soldiers for many years. These have included Count Laszlo de Almasy (on whom the novel The English Patient was based) and modern geologist Tom Brown. Some believe that in recent petroleum excavations, the remains may have be uncovered. A 2002 novel by Paul Sussman The Lost Army Of Cambyses recounts the story of rival archaeological expeditions searching for the remains.

The Stone Tablets of Darius the Great

The Persian Rosetta Stone

Seal of Darius the Great

The empire then reached its greatest extent under Darius I. He led conquering armies into the Indus River valley and into Thrace in Europe. His invasion of Greece was halted at the Battle of Marathon.

Darius I, who ascended the throne in 521 BC, pushed the Persian borders as far eastward as the Indus River, had a canal constructed from the Nile to the Red Sea, and reorganized the entire empire, earning the title 'Darius the Great.'

Darius (Greek form Dareios) is a classicized form of the Old Persian Daraya-Vohumanah, Darayavahush or Darayavaush, which was the name of three kings of the Achaemenid Dynasty of Persia: Darius I (the Great), ruled 522-486 BCE, Darius II (Ochos), ruled 423-405/4 BCE, and Darius III (Kodomannos), ruled 336-330 BCE. In addition to these, the oldest son of Xerxes I was named Darius, but he was murdered before he ever came to the throne, and Darius, the son of Artaxerxes II, was executed for treason against his own father.

According to A. T. Olmstead's book History of the Persian Empire, Darius the Great's father Vishtaspa (Hystaspes) and mother Hutaosa (Atossa) knew the prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster) personally and were converted by him to the new religion he preached, Zoroastrianism.

The empire of Darius the Great extended from Egypt in the west to the Indus River in the east. The major satrapies or provinces of his Empire were connected to the center at Persepolis, in the Fars Province of present-day Iran. The Royal Road connected 111 stations to each other. Messengers riding swift horses informed the king within days of turmoil brewing in lands as distant as Egypt and Sughdiana.

One of the most awe-inspiring monuments of the ancient world, Persepolis was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenian empire. It was built during the reign of Darius I, known as Darius the Great (522-485 BC), and developed further by successive kings. The various temples and monuments are located upon a vast platform, some 450 metres by 300 metres and 20 metres in height. At the head of the ceremonial staircase leading to the terrace is the 'Gateway of All Nations' built by Xerxes I and guarded by two colossal bull-like figures.

Darius was the greatest of all the Persian kings. He extended the empires borders into India and Europe. He also fought two wars with the Greeks which were disastrous.

Darius established a government which became a model for many future governments:

- Established a tax-collection system;

- Allowed locals to keep customs and religions;

- Divided his empire into districts known as Satrapies;

- Built a system of roads still used today;

- Established a complex postal system;

- Established a network of spies he called the "Eyes and Ears of the King."

- Built two new capital cities, one at Susa and one at Persepolis.

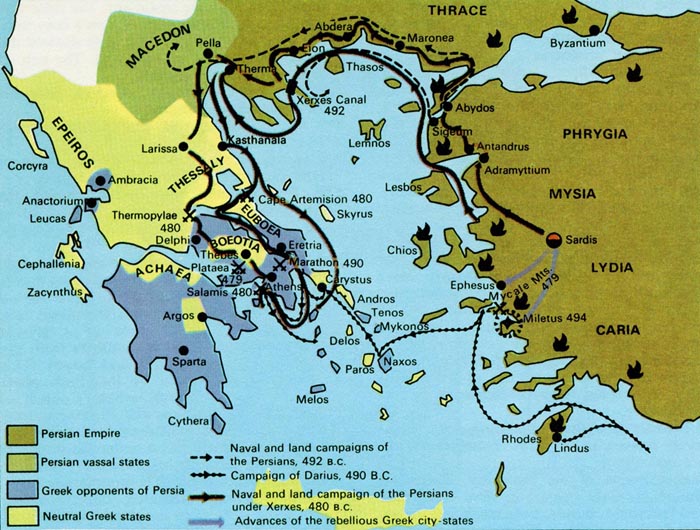

In the 5th century BC the vast Persian Empire attempted to conquer Greece. If the Persians had succeeded, they would have set up local tyrants, called 'satraps', to rule Greece and would have crushed the first stirrings of democracy in Europe. The survival of Greek culture and political ideals depended on the ability of the small, disunited Greek city-states to band together and defend themselves against Persia's overwhelming strength. The struggle, known in Western history as the Persian Wars, or Greco-Persian Wars, lasted 20 years -- from 499 to 479 BC.

Persia already numbered among its conquests the Greek cities of Ionia in Asia Minor, where Greek civilization first flourished. The Persian Wars began when some of these cities revolted against Darius I, Persia's king, in 499 BC.

Athens sent 20 ships to aid the Ionians. Before the Persians crushed the revolt, the Greeks burned Sardis, capital of Lydia. Angered, Darius determined to conquer Athens and extend his empire westward beyond the Aegean Sea.

In 492 BC Darius gathered together a great military force and sent 600 ships across the Hellespont. A sudden storm wrecked half his fleet when it was rounding rocky Mount Athos on the Macedonian coast.

Two years later Darius dispatched a new battle fleet of 600 triremes. This time his powerful galleys crossed the Aegean Sea without mishap and arrived safely off Attica, the part of Greece that surrounds the city of Athens.

The Persians landed on the plain of Marathon, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) from Athens. When the Athenians learned of their arrival, they sent a swift runner, Pheidippides, to ask Sparta for aid, but the Spartans, who were conducting a religious festival, could not march until the moon was full. Meanwhile the small Athenian army encamped in the foothills on the edge of the Marathon Plain.

The Athenian general Miltiades ordered his small force to advance. He had arranged his men so as to have the greatest strength in the wings. As he expected, his center was driven back. The two wings then united behind the enemy. Thus hemmed in, the Persians' bows and arrows were of little use. The stout Greek spears spread death and terror. The invaders rushed in panic to their ships. The Greek historian Herodotus says the Persians lost 6,400 men against only 192 on the Greek side. Thus ended the battle of Marathon (490 BC), one of the decisive battles of the world.

Darius planned another expedition, but he died before preparations were completed. This gave the Greeks a ten-year period to prepare for the next battles. Athens built up its naval supremacy in the Aegean under the guidance of Themistocles.

In 480 BC the Persians returned, led by King Xerxes, the son of Darius. To avoid another shipwreck off Mount Athos, Xerxes had a canal dug behind the promontory. Across the Hellespont he had the Phoenicians and Egyptians place two bridges of ships, held together by cables of flax and papyrus. A storm destroyed the bridges, but Xerxes ordered the workers to replace them. For seven days and nights his soldiers marched across the bridges.

On the way to Athens, Xerxes found a small force of Greek soldiers holding the narrow pass of Thermopylae, which guarded the way to central Greece. The force was led by Leonidas, king of Sparta. Xerxes sent a message ordering the Greeks to deliver their arms. "Come and take them," replied Leonidas.

For two days the Greeks' long spears held the pass. Then a Greek traitor told Xerxes of a roundabout path over the mountains. When Leonidas saw the enemy approaching from the rear, he dismissed his men except the 300 Spartans, who were bound, like himself, to conquer or die. Leonidas was one of the first to fall. Around their leader's body the gallant Spartans fought first with their swords, then with their hands, until they were slain to the last man.

The Persians moved on to Attica and found it deserted. They set fire to Athens with flaming arrows. Xerxes' fleet held the Athenian ships bottled up between the coast of Attica and the island of Salamis. His ships outnumbered the Greek ships three to one. The Persians had expected an easy victory, but one after another their ships were sunk or crippled.

Crowded into the narrow strait, the heavy Persian vessels moved with difficulty. The lighter Greek ships rowed out from a circular formation and rammed their prows into the clumsy enemy vessels. Two hundred Persian ships were sunk, others were captured, and the rest fled. Xerxes and his forces hastened back to Persia.

Soon after, the rest of the Persian army was scattered at Plataea (479 BC). In the same year Xerxes' fleet was defeated at Mycale. Although a treaty was not signed until 30 years later, the threat of Persian domination was ended.

Darius was killed in a coup led by other family members. At the time, he was preparing a new expedition against the Greeks. His son and successor, Xerxes I, attempted to fulfill his plan.

Enthroned in Peresepolis, the magnificent city that he built, Darius I firmly grasps the royal scepter in his right hand. In the left, he is holding a lotus blossom with two buds, the symbol of royalty.

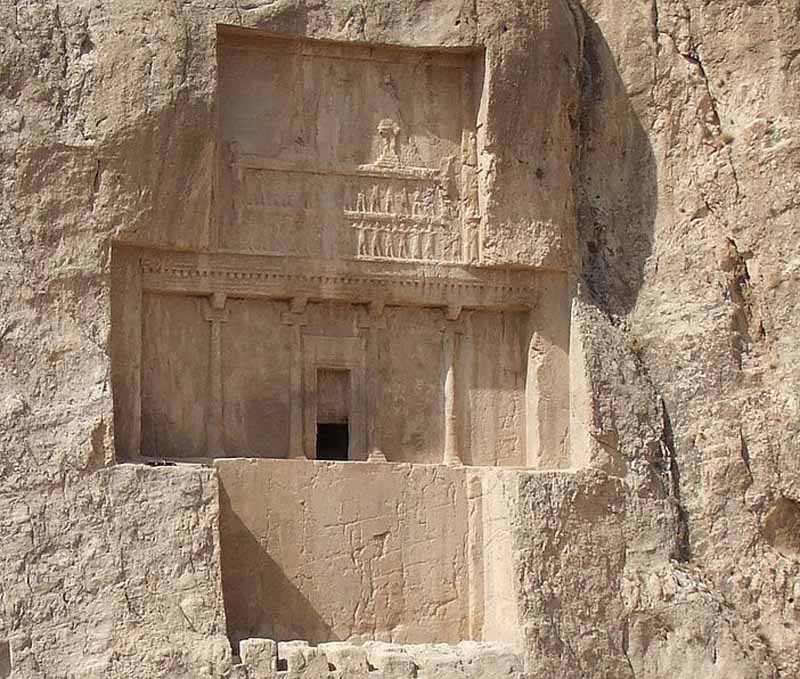

Tomb of Darius

Xerxes

Xerxes was king of Persia from 486-465 BCE. His real name was Ahasuerus. 'X�e�r�x�e�s'� �i�s� �t�h�e� �G�r�e�e�k� �t�r�a�n�s�l�i�t�e�r�a�t�i�o�n� �o�f� �t�h�e� �P�e�r�s�i�a�n� �t�h�r�o�n�e� �n�a�m�e� �'K�h�s�h�a�y�a�r�s�h�a�' �o�r� '�K�h�s�h�a�-�y�a�r�-�s�h�a�n'�,� �m�e�a�n�i�n�g� �'�r�u�l�e�r� �o�f� �h�e�r�o�e�s�'�.� �I�n� �t�h�e� �H�e�b�r�e�w� �B�i�b�l�e�,� �t�h�e� �P�e�r�s�i�a�n� �k�i�n�g� �A�h�a�s�u�e�r�u�s� �i�n� �G�r�e�e�k� �p�r�o�b�a�b�l�y� �c�o�r�r�e�s�p�o�n�d�s� �t�o� �X�e�r�x�e�s� �I�.

Xerxes was king of Persia from 486-465 BCE. His real name was Ahasuerus. 'X�e�r�x�e�s'� �i�s� �t�h�e� �G�r�e�e�k� �t�r�a�n�s�l�i�t�e�r�a�t�i�o�n� �o�f� �t�h�e� �P�e�r�s�i�a�n� �t�h�r�o�n�e� �n�a�m�e� �'K�h�s�h�a�y�a�r�s�h�a�' �o�r� '�K�h�s�h�a�-�y�a�r�-�s�h�a�n'�,� �m�e�a�n�i�n�g� �'�r�u�l�e�r� �o�f� �h�e�r�o�e�s�'�.� �I�n� �t�h�e� �H�e�b�r�e�w� �B�i�b�l�e�,� �t�h�e� �P�e�r�s�i�a�n� �k�i�n�g� �A�h�a�s�u�e�r�u�s� �i�n� �G�r�e�e�k� �p�r�o�b�a�b�l�y� �c�o�r�r�e�s�p�o�n�d�s� �t�o� �X�e�r�x�e�s� �I�.

Xerxes I The Great, was the son of Darius I The Great and Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus the Great. He was appointed successor to his father in preference to his eldest half-brother, who were born before Darius had become king.

After his accession in October 485 BC he suppressed the revolt in Egypt which had broken out in 486 BC, appointed his brother Achaemenes as henchman (or khshathrapavan, satrap) bringing Egypt under a very strict rule.

His predecessors, especially Darius, had not been successful in their attempts to conciliate the ancient civilizations. This probably was the reason why Xerxes in 484 BC abolished the Kingdom of Babel and took away the golden statue of Bel (Marduk, Merodach), the hands of which the legitimate king of Babel had to seize on the first day of each year, and killed the priest who tried to hinder him.

Therefore Xerxes does not bear the title of King of Babel in the Babylonian documents dated from his reign, but King of Persia and Media or simply King of countries (i.e. of the world). This proceeding led to two rebellions, probably in 484 BC and 479 BC.

Darius had left to his son the task of punishing the Greeks for their interference in the Ionian rebellion and the victory of Marathon. From 483 Xerxes prepared his expedition with great care: a channel was dug through the isthmus of the peninsula of Mount Athos; provisions were stored in the stations on the road through Thrace; two bridges were thrown across the Hellespont.

Xerxes concluded an alliance with Carthage, and thus deprived Greece of the support of the powerful monarchs of Syracuse and Agrigentum. Many smaller Greek states, moreover, took the side of the Persians, especially Thessaly, Thebes and Argos.

A large fleet and a numerous army (some have claimed that there were over 2,000,000) were gathered. In the spring of 480 Xerxes set out from Sardis. At first Xerxes was victorious everywhere. The Greek fleet was beaten at Artemisium, Thermopylae stormed, Athens conquered, the Greeks driven back to their last line of defence at the Isthmus of Corinth and in the Saronic Gulf.

But Xerxes was induced by the astute message of Themistocles (against the advice of Artemisia of Halicarnassus) to attack the Greek fleet under unfavourable conditions, instead of sending a part of his ships to the Peloponnesus and awaiting the dissolution of the Greek armament.

The Battle of Salamis (September 28, 480) decided the war. Having lost his communication by sea with Asia, Xerxes was forced to retire to Sardis; the army which he left in Greece under Mardonius was in 479 beaten at Plataea. The defeat of the Persians at Mycale roused the Greek cities of Asia.

Of the later years of Xerxes little is known. He sent out Satapes to attempt the circumnavigation of Africa, but the victory of the Greeks threw the empire into a state of slow apathy, from which it could not rise again. The king himself became involved in intrigues of the harem and was much dependent upon courtiers and eunuchs. He left inscriptions at Persepolis, where he added a new palace to that of Darius, at Van in Armenia, and on Mount Elvend near Ecbatana. In these texts he merely copies the words of his father. In 465 he was murdered by his vizier Artabanus who raised Artaxerxes I to the throne.

In the Bible, in the Book of Ezra, Xerxes I is mentioned by the name 'Ashverosh' (Ahasuerus in Greek). It is noted that, during his reign, as in the reign of his predecessor Darius and his successor Artaxerxes, the Samaritans wrote to the Persian king full of accusations against the Jews.Ahasuerus also appears as the King in the Book of Esther, and is traditionally identified with Xerxes.

In the story told in this Biblical book, Ahasuerus dismisses his Queen consort Vashti and then chooses the Jewess Esther as his queen. The king's minister Haman, feeling insulted by Esther's cousin Mordecai, convinces Ahasuerus to decree the destruction of all the Jews in the Persian Empire, but Mordecai and Esther manage to reverse their fate through their influence with the King.

Neither Vashti nor Esther are known from other sources. According to Herodotus, the Queen consort of Xerxes was actually Amestris, daughter to Otanes. Most historians consider the 'Book of Esther' to be a historical fiction, and assume that the events depicted therein did not actually occur.

Artaxerxes continued building work at Persepolis. It was completed during the reign of Artaxerxes III, around 338 BC. In 334 BC, Alexander the Great defeated the Persian armies of the third Darius. He marched into Iran and, once there, he turned his attention to Persepolis, and that magnificent complex of buildings was burnt down. This act of destruction for revenge of the Acropolis, was surprising from one who prided himself on being a pupil of Aristotle. This was the end of the Persian Empire.

Xerxes's Hall of the 100 Columns is the most impressive building in the complex. It is also the most crowded--a jumble of fallen columns, column heads, and column bases.

The Gate of Xerxes at Perespolis shows that the Winged Lion was placed at the corner of one entrance. When you stood in front of the gate you saw a lion with four legs and when you were inside the gate you also saw a lion with four legs.

No comments:

Post a Comment