Spanish Flu

Period: January 1918 – December 1920 Trending

Virus strain: H1N1

First outbreak: Disputed

Confirmed cases: 500 million (estimate)

Disease: Influenza

Number of deaths: 50,000,000

An influenza ward at a U.S. Army Camp Hospital in France during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. (Image: © Shutterstock)

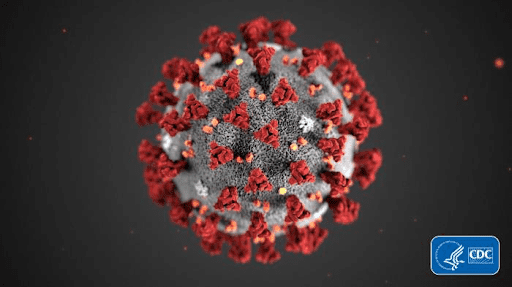

COVID-19 2019-2020 (Photo by Malik Shabazz)

20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

By Owen Jarus - Live Science Contributor, All About History March 20, 2020Plagues and epidemics have ravaged humanity throughout its existence, often changing the course of history.

Throughout the course of history, disease outbreaks have ravaged humanity, sometimes changing the course of history and, at times, signaling the end of entire civilizations. Here are 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics, dating from prehistoric to modern times.

1. Prehistoric epidemic: Circa 3000 B.C.

The discovery of a 5,000-year-old house in China filled with skeletons is evidence of a deadly epidemic. (Image credit: Photo courtesy Chinese Archaeology)

About 5,000 years ago, an epidemic wiped out a prehistoric village in China. The bodies of the dead were stuffed inside a house that was later burned down. No age group was spared, as the skeletons of juveniles, young adults and middle-age people were found inside the house. The archaeological site is now called "Hamin Mangha" and is one of the best-preserved prehistoric sites in northeastern China. Archaeological and anthropological study indicates that the epidemic happened quickly enough that there was no time for proper burials, and the site was not inhabited again.

Before the discovery of Hamin Mangha, another prehistoric mass burial that dates to roughly the same time period was found at a site called Miaozigou, in northeastern China. Together, these discoveries suggest that an epidemic ravaged the entire region.

Remains of the Parthenon, one of the buildings on the acropolis of Athens. The city experienced a five year pandemic around 430 B.C. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

What exactly this epidemic was has long been a source of debate among scientists; a number of diseases have been put forward as possibilities, including typhoid fever and Ebola. Many scholars believe that overcrowding caused by the war exacerbated the epidemic. Sparta's army was stronger, forcing the Athenians to take refuge behind a series of fortifications called the "long walls" that protected their city. Despite the epidemic, the war continued on, not ending until 404 B.C., when Athens was forced to capitulate to Sparta.

3. Antonine Plague: A.D. 165-180

Roman soldiers likely brought smallpox home with them, giving rise to the Antonine Plague. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

Many historians believe that the epidemic was first brought into the Roman Empire by soldiers returning home after a war against Parthia. The epidemic contributed to the end of the Pax Romana (the Roman Peace), a period from 27 B.C. to A.D. 180, when Rome was at the height of its power. After A.D. 180, instability grew throughout the Roman Empire, as it experienced more civil wars and invasions by "barbarian" groups. Christianity became increasingly popular in the time after the plague occurred.

4. Plague of Cyprian: A.D. 250-271

The remains found where a bonfire incinerated many of the victims of an ancient epidemic in the city of Thebes in Egypt. (Image credit: N.Cijan/Associazione Culturale per lo Studio dell'Egitto e del Sudan ONLUS)

Named after St. Cyprian, a bishop of Carthage (a city in Tunisia) who described the epidemic as signaling the end of the world, the Plague of Cyprian is estimated to have killed 5,000 people a day in Rome alone. In 2014, archaeologists in Luxor found what appears to be a mass burial site of plague victims. Their bodies were covered with a thick layer of lime (historically used as a disinfectant). Archaeologists found three kilns used to manufacture lime and the remains of plague victims burned in a giant bonfire.

5. Plague of Justinian: A.D. 541-542

A mosaic of Emperor Justinian and his supporters. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

The plague is named after the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (reigned A.D. 527-565). Under his reign, the Byzantine Empire reached its greatest extent, controlling territory that stretched from the Middle East to Western Europe. Justinian constructed a great cathedral known as Hagia Sophia ("Holy Wisdom") in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), the empire's capital. Justinian also got sick with the plague and survived; however, his empire gradually lost territory in the time after the plague struck.

6. The Black Death: 1346-1353

Illustration from Liber chronicarum, 1. CCLXIIII; Skeletons are rising from the dead for the dance of death. (Image credit: Anton Koberger, 1493/Public domain)

The Black Death traveled from Asia to Europe, leaving devastation in its wake. Some estimates suggest that it wiped out over half of Europe's population. It was caused by a strain of the bacterium Yersinia pestis that is likely extinct today and was spread by fleas on infected rodents. The bodies of victims were buried in mass graves.

The plague changed the course of Europe's history. With so many dead, labor became harder to find, bringing about better pay for workers and the end of Europe's system of serfdom. Studies suggest that surviving workers had better access to meat and higher-quality bread. The lack of cheap labor may also have contributed to technological innovation.

7. Cocoliztli epidemic: 1545-1548

Aztec Ruins National Monument. (Image credit: USGS)

A recent study that examined DNA from the skeletons of victims found that they were infected with a subspecies of Salmonella known as S. paratyphi C, which causes enteric fever, a category of fever that includes typhoid. Enteric fever can cause high fever, dehydration and gastrointestinal problems and is still a major health threat today.

8. American Plagues: 16th century

Painting by O. Graeff (1892) of Hernán Cortéz and his troops. The Spanish conqueror was able to capture Aztec cities left devastated by smallpox. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

The diseases helped a Spanish force led by Hernán Cortés conquer the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519 and another Spanish force led by Francisco Pizarro conquer the Incas in 1532. The Spanish took over the territories of both empires. In both cases, the Aztec and Incan armies had been ravaged by disease and were unable to withstand the Spanish forces. When citizens of Britain, France, Portugal and the Netherlands began exploring, conquering and settling the Western Hemisphere, they were also helped by the fact that disease had vastly reduced the size of any indigenous groups that opposed them.

9. Great Plague of London: 1665-1666

A model re-enactment of the 1666 Great Fire of London. The fire occured right after the city suffered through a devastating plague. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

10. Great Plague of Marseille: 1720-1723

Present day view of Saint Jean Castle and Cathedral de la Major and the Vieux port in Marseille, France. Up to 30% of the population of Marseille died as a result of a three-year plague epidemic in the 1720s. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

Plague spread quickly, and over the next three years, as many as 100,000 people may have died in Marseille and surrounding areas. It's estimated that up to 30% of the population of Marseille may have perished.

11. Russian plague: 1770-1772

Portrait of Catherine II by Vigilius Erichsen (ca. 1757-1772). Even Catherine the Great couldn't bring Russia back from the devastation caused by the 1770 plague. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

The empress of Russia, Catherine II (also called Catherine the Great), was so desperate to contain the plague and restore public order that she issued a hasty decree ordering that all factories be moved from Moscow. By the time the plague ended, as many as 100,000 people may have died. Even after the plague ended, Catherine struggled to restore order. In 1773, Yemelyan Pugachev, a man who claimed to be Peter III (Catherine's executed husband), led an insurrection that resulted in the deaths of thousands more.

12. Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic: 1793

Painting of George Washington's second inauguration at Congress Hall in Philadelphia, March 4, 1793. An epidemic of yellow fever hit Philadelphia hard in the first half of 1793. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

The disease is carried and transmitted by mosquitoes, which experienced a population boom during the particularly hot and humid summer weather in Philadelphia that year. It wasn't until winter arrived — and the mosquitoes died out — that the epidemic finally stopped. By then, more than 5,000 people had died.

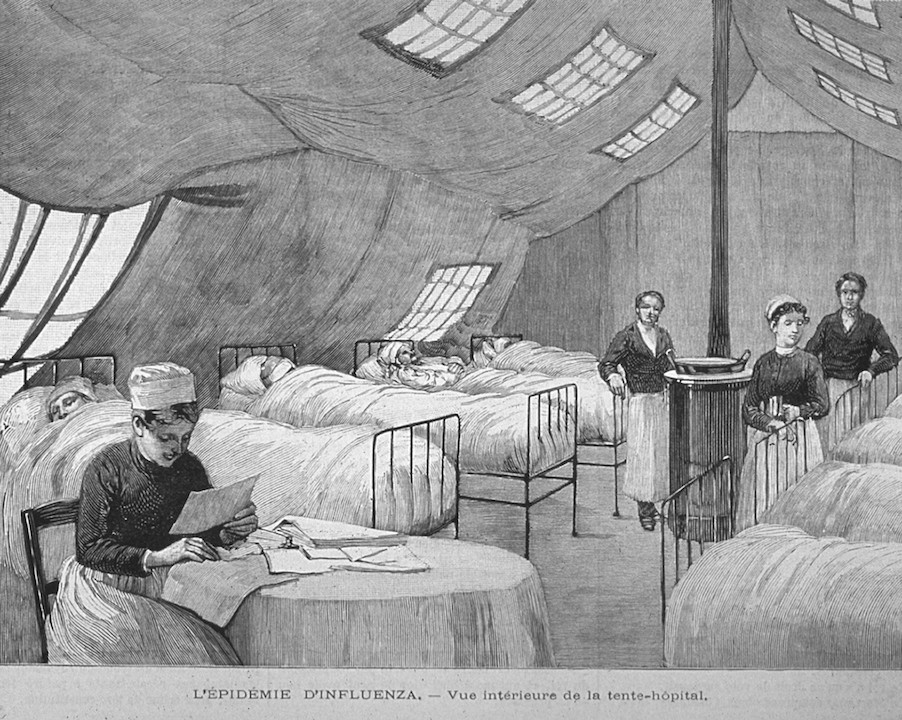

13. Flu pandemic: 1889-1890

Wood engraving showing nurses attending to patients in Paris during the 1889-90 flu pandemic. The pandemic killed an estimated 1 million people. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

The earliest cases were reported in Russia. The virus spread rapidly throughout St. Petersburg before it quickly made its way throughout Europe and the rest of the world, despite the fact that air travel didn't exist yet.

14. American polio epidemic: 1916

Franklin D. Roosevelt memorial in Washington, D.C. President Roosevelt was diagnosed with polio in 1921, at the age of 39. Polio killed thousands until the development of the Salk vaccine in 1954. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

Polio epidemics occurred sporadically in the United States until the Salk vaccine was developed in 1954. As the vaccine became widely available, cases in the United States declined. The last polio case in the United States was reported in 1979. Worldwide vaccination efforts have greatly reduced the disease, although it is not yet completely eradicated.

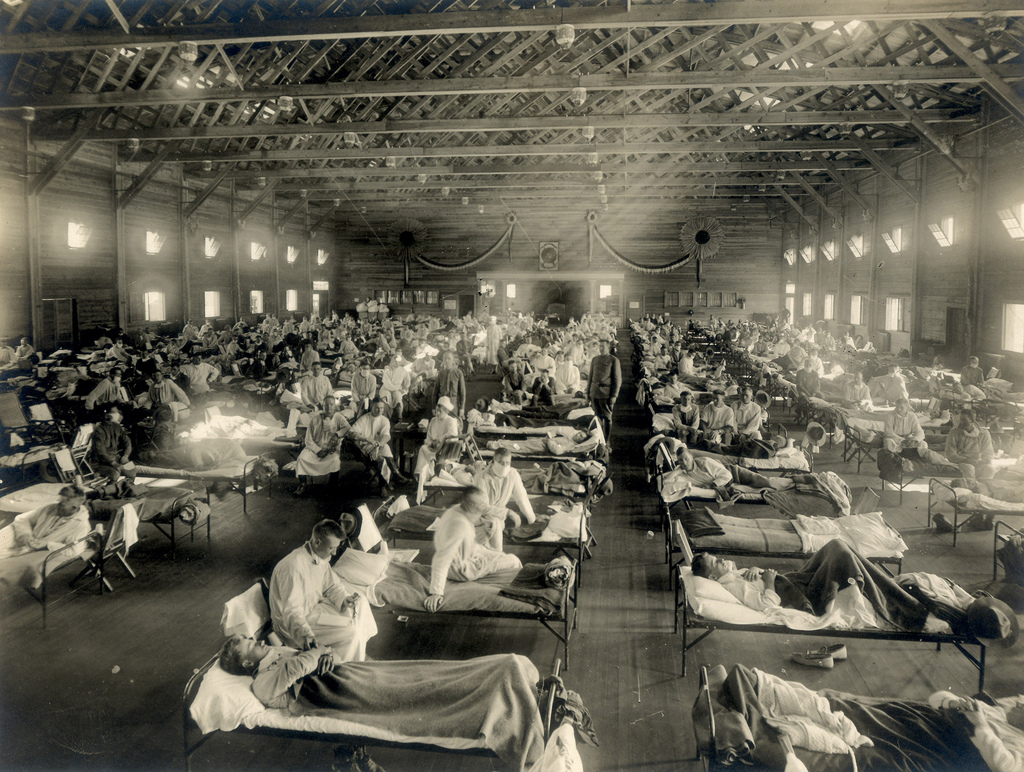

15. Spanish Flu: 1918-1920

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas. (Image credit: Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine)

Despite the name Spanish Flu, the disease likely did not start in Spain. Spain was a neutral nation during the war and did not enforce strict censorship of its press, which could therefore freely publish early accounts of the illness. As a result, people falsely believed the illness was specific to Spain, and the name Spanish Flu stuck.

{1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus) The 1918 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. It was caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. Although there is not universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, it spread worldwide during 1918-1919.}

{The Spanish flu, also known as the 1918 flu pandemic, was an unusually deadly influenza pandemic. Lasting from January 1918 to December 1920, it infected 500 million people – about a third of the world's population at the time.}

16. Asian Flu: 1957-1958

Chickens being tested for the avian flu. An outbreak of the avian flu killed 1 million people in the late 1950s. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that the disease spread rapidly and was reported in Singapore in February 1957, Hong Kong in April 1957, and the coastal cities of the United States in the summer of 1957. The total death toll was more than 1.1 million worldwide, with 116,000 deaths occurring in the United States.

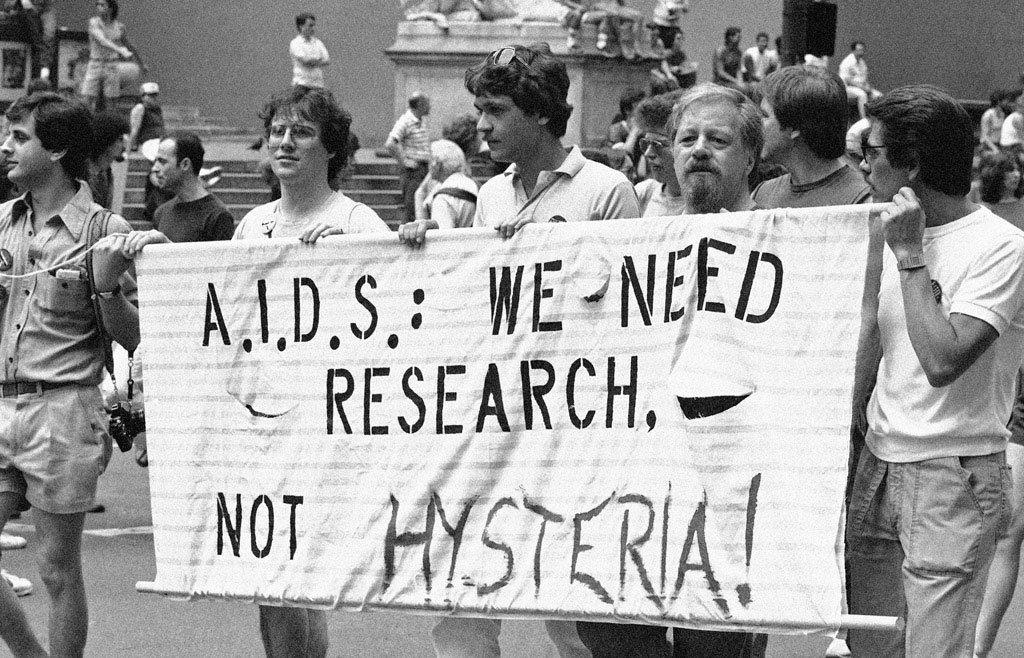

17. AIDS pandemic and epidemic: 1981-present day

AIDS became a global pandemic in the 1980s and continues as an epidemic in certain parts of the world. (Image credit: Mario Suriani/Associated Press, via the New York Historical Society)

For decades, the disease had no known cure, but medication developed in the 1990s now allows people with the disease to experience a normal life span with regular treatment. Even more encouraging, two people have been cured of HIV as of early 2020.

18. H1N1 Swine Flu pandemic: 2009-2010

A nurse walking by a triage tent set up outside of the emergency room at Sutter Delta Medical Center in Antioch, California on April 30, 2009. The hospital was preparing for a potential flood of patients worried they might have swine flu. (Image credit: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

The 2009 flu pandemic primarily affected children and young adults, and 80% of the deaths were in people younger than 65, the CDC reported. That was unusual, considering that most strains of flu viruses, including those that cause seasonal flu, cause the highest percentage of deaths in people ages 65 and older. But in the case of the swine flu, older people seemed to have already built up enough immunity to the group of viruses that H1N1 belongs to, so weren't affected as much. A vaccine for the H1N1 virus that caused the swine flu is now included in the annual flu vaccine.

19. West African Ebola epidemic: 2014-2016

Health care workers put on protective gear before entering an Ebola treatment unit in Liberia during the 2014 Ebola outbreak. (Image credit: CDC/Sally Ezra/Athalia Christie (Public Domain))

Ebola ravaged West Africa between 2014 and 2016, with 28,600 reported cases and 11,325 deaths. The first case to be reported was in Guinea in December 2013, then the disease quickly spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone. The bulk of the cases and deaths occurred in those three countries. A smaller number of cases occurred in Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, the United States and Europe, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

There is no cure for Ebola, although efforts at finding a vaccine are ongoing. The first known cases of Ebola occurred in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1976, and the virus may have originated in bats.

20. Zika Virus epidemic: 2015-present day

A worker sprays pesticide to kill mosquitoes that carry the Zika virus. Zika is most prevalent in the tropics. (Image credit: Shutterstock)

The impact of the recent Zika epidemic in South America and Central America won't be known for several years. In the meantime, scientists face a race against time to bring the virus under control. The Zika virus is usually spread through mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, although it can also be sexually transmitted in humans.

While Zika is usually not harmful to adults or children, it can attack infants who are still in the womb and cause birth defects. The type of mosquitoes that carry Zika flourish best in warm, humid climates, making South America, Central America and parts of the southern United States prime areas for the virus to flourish.

Additional resources:

- Learn what a pandemic is.

- Discover what the coronavirus outbreak can teach us about bringing samples back from Mars.

- Learn about how the spread of COVID-19 is fueled through stealth transmission.