Egypt - The Third Dynasty - (2686 - 2575 BC)

The Old Kingdom - The Age of the Pyramids

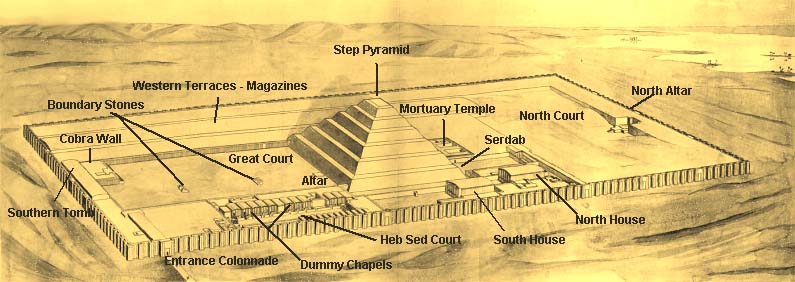

The Pharaohs of the Third Dynasty were the first to have actual pyramids constructed as shrines to their deaths. Although crude, these step pyramids were the predecessors to the later Pyramids of Giza and others. The first of these pyramids was designed by Imhotep for Dzoser. Prior to, and during the construction of the step pyramids, rulers were buried in a structure called a Mastaba.

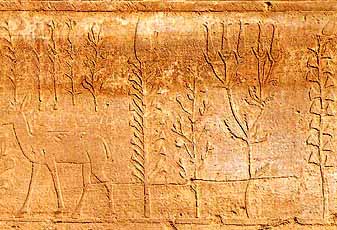

- A mastaba was a flatroofed, mudbrick, rectangular building with sloping sides that marked the burial site of many eminent Egyptians of the Egypt's ancient period.

Mastaba comes from the Arabic for bench, because they look like a mud bench when seen from a distance. In a mastaba, a deep chamber was dug out and lined with stone, mud bricks or wood. Above ground, the mud was piled up to mark the grave, oblong in a shape with a length approximately 4 times its width. Although this provided a much grander tomb, it was also a much cooler tomb. This upset the early priests as it allowed the bodies to decompose due to the fact that water no longer evaporated, preventing desiccation of the bodies.

The Mastaba were the standard tomb type in early Egypt (the predynastic and early dynastic periods.

While Manetho names one Necherophes, and the Turin King List names Nebka, as the first pharaoh of the Third Dynasty of Egypt, some contemporary Egyptologists believe Djoser was the first king of this dynasty, pointing out that the order in which some predecessors of Khufu are mentioned in the Papyrus Westcar suggests that Nebka should be placed between Djoser and Huni, and not before Djoser. That the Turin King List has noted Djoser's name in red may also be significant.

In any case, Djoser is the best known king of this dynasty, for commissioning his vizier Imhotep to build the earliest surviving pyramids, the Step Pyramid. Some authorities believe that Imhotep lived into the reign of the Pharaoh Huni.

Little is known for certain of Sekhemkhet. However, it is believed that Khaba possibly built the Layer Pyramid at Zawyet el'Aryan. Huni, the last king of this dynasty, like Djoser had a renowned vizier, named Khagemni. In the Ramassid period, a text named the Instructions was ascribed to Kagemni.

- The Layer Pyramid (known locally in Arabic as Haram el-Meduwara, or Round Pyramid) is located in the necropolis of Zawyet el'Aryan. It is thought to be the tomb of Khaba, of the Third Dynasty, but this is based upon excavations in a tomb inside the pyramid complex, and is disputed.

Uncertainty swirls around the placement, and also the events of the 3rd Dynasty king known as Sanakhte (Sanakht). He may have been Nebka, who was known to manetho, and listed on both the Turin Cannon and the Abydos king list as the first king of this dynasty. However, this is problematic to say the least, for we base our belief that he was Nebka on a source that lists his Horus name, Sanakhte, together with a second name that ends with the element "ka" Most of the information we have on this king refers to him as Nebka. In fact, some sources list the two as separate kings, with Nebka founding the 3rd Dynasty and Sanakhte ruling later, perhaps after Khaba.

However, despite this, mud seal impressions bearing the name of Nethery-khet Djoser from the Abydos tomb of the last king of the 2nd Dynasty Khasekhemuy and connected with the burial seem to suggest that Khasekhemuy's widow and her already ruling son Djoser were in charge of the king's burial. On the basis of sealing from the tomb of Khasekhemwy, which name her as "Mother of the King's Children," the wife of the last ruler of the 2nd Dynasty seems to have been one Nimaethap. The latter name was also found, with the title of "King's Mother", upon seal impressions from Mastaba K1 at Beit Khallaf, a gigantic monument dated to the reign of Djoser. Hence, on the basis that Djoser was succeeded by Sekhemkhet and of indications pointing to Khaba as the third in line, Nebka may have been the fourth king of the dynasty, to be equated with the Nebkara following Djoser-teti and preceding Huni in the Saqqara king list.

Many theories regarding the rule of Sanakhte have been advanced, including the possibility that Sanakhte, as a member of a former ruling family, usurped the throne from the ruling family at the beginning of the dynasty. Hence, Djoser could have indeed buried his father, Khasekhemuy, and won back the throne from the usurper, Sanakhte. However, we are told that today, most Egyptologists do believe that he was a latter king of the Dynasty, even though most current documentary resources continue to equate Sanakhte with Nebka, as the 1st King of Egypt's noteworthy 3rd Dynasty who probably ruled from This near Abydos.

Little is known of this king, despite a reign of some 18 or 19 years (others might attribute a much shorter reign of from five to seven years, which would allow a better fit for him ruling before Djoser), for his reign is missing from the Palermo Stone, and important source of information on this period of Egyptian history. However, Nebka is mentioned in Papyrus Westcar. The only large scale monumental building that can possibly be attributed to him is at Beit Khallaf (mastaba K2).

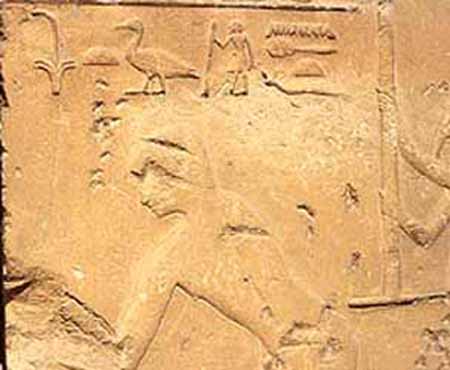

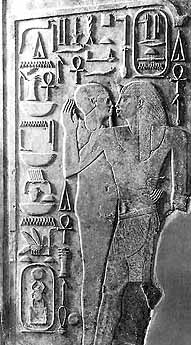

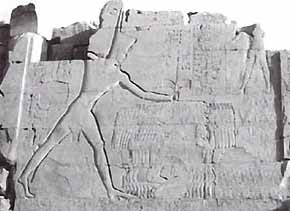

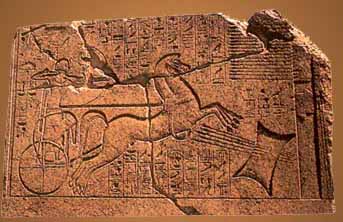

His name also appears on the island of Elephantine in southern Egypt near Aswan on a small pyramid. Another of the few sources we have evidencing this king is a fragment of a sandstone relief from Wadi Maghara in the Sinai. It would seem that he, along with Djoser, began the exploitation in earnest of the mineral wealth of the Sinai peninsula, with its rich deposits of turquoise and copper. It shows the king's name in a serekh before his face.

The relief depicts Sanakhte, who is about to smite an enemy, wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. We also know of a priest of Nebka's mortuary cult who appears to have lived in the reign of Djoser.

Some Egyptologists continue to believe that he may have been the brother of his famous successor, Djoser (or Zoser), or if not, perhaps his father, but apparently current thought among Egyptologists leans against this. It has been suggested that his tomb at Saqqara was incorporated into the Step Pyramid of Djoser, though little real evidence for this exists, but it has also been suggested that his is a little known monument that seems to nicely fill the typological lacuna between the Shunet el Zebib and the Step Pyramid at Saqqara.

Other spellings of his name include: Zoser, Dzoser, Zozer (or Zozzer), Dsr, Djeser, Zoser, Zosar, Djéser, Djeser, Horus-Netjerikhet, Horus-Netjerichet.

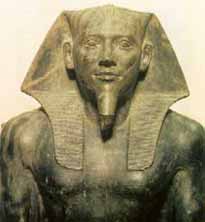

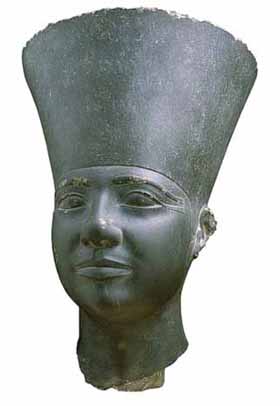

Netjerikhet Djoser (Turin King List "Dsr-it"; Manetho "Tosarthros") is the best-known pharaoh of the Third Dynasty of Egypt, for commissioning his vizier Imhotep to build his Step Pyramid at Saqqara.

In contemporary inscriptions, he is called Netjerikhet, meaning body of the gods. Later sources, which include a New Kingdom reference to his Step Pyramid, help confirm that Netjerikhet and Djoser are the same person.

While Manetho names one Necherophes, and the Turin King List names Nebka, as the first ruler of the Third dynasty, some contemporary Egyptologists believe Djoser was the first king of this dynasty, pointing out that the order in which some predecessors of Khufu are mentioned in the Papyrus Westcar suggests that Nebka should be placed between Djoser and Huni, and not before Djoser.

Westcar Papyrus is a document about Khufu, a 4th-Dynasty Egyptian leader, and contains a cycle of five stories about marvels performed by priests. Each of these tales is being told at the court of Khufu by his sons.

Manetho also states Djoser ruled for 29 years, while the Turin King List states it was for 19. It is possible that Manetho's number is a mistake for the earlier Turin King List; and it is also possible that the author of the Turin King List confused the bi-annual cattle censuses as years, and that Djoser actually reigned for 37 or 38 years. Because of his many building projects, particularly at Saqqara, some scholars argue that Djoser must have ruled for at least 29 years.

Because Queen Nimaethap, the wife of Khasekhemwy, the last king of the Second dynasty of Egypt, appears to have held the title of "Mother of the King", some writers argue that she was Djoser's mother and Khasekhemwy was his father. Three royal women are known from during his reign: Inetkawes, Hetephernebti and a third, whose name is destroyed. One of them might have been his wife, and the one whose name is lost may have been Nimaethap. The relationship between Djoser and his successor, Sekhemkhet, is not known.

Djoser sent several military expeditions to the Sinai Peninsula, during which the local inhabitants were subdued. He also sent expeditions to the Sinai where they mined for valuable minerals like turquoise and copper. It was also strategically important as a buffer between Asia and the Nile valley. He also may have fixed the southern boundary of his kingdom at the First Cataract.

Some fragmentary reliefs found at Heliopolis and Gebelein mention Djoser's name and suggest that he had commissioned construction projects in those cities. An inscription claiming to date to the reign of Djoser, but actually created during the Ptolemaic Dynasty, relates how Djoser rebuilt the temple of the god Khnum on the island of Elephantine at the First Cataract, thus ending a famine in Egypt. While this inscription is but a legend, it does show that more than two millennia after his reign, Djoser was still remembered.

Sekhemkhet was Pharaoh in Egypt during the Third dynasty. According to Manethonian tradition, a king known as "Djoserty" reigned a relatively brief seven years, and modern scholars believe Djoserty and Sekhemkhet to be the same person. His reign would thought to have been from about 2649 BC until 2643 BC.

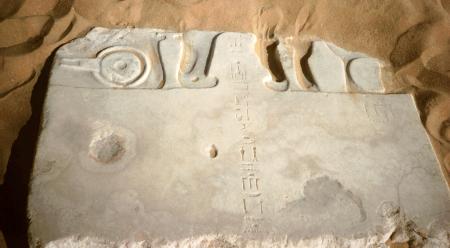

While there was a known successor to Djoser, Sekhemkhet's name was unknown until 1951, when the leveled foundation and vestiges of an unfinished Step Pyramid were discovered at Saqqara by Zakaria Goneim. Only the lowest step of the pyramid had been constructed at the time of his death.

Jar seals found on the site were inscribed with this king's name. From its design and an inscription from his pyramid at Saqqara, it is thought that Djoser's famous architect Imhotep had a hand in the design of this pyramid.

Archaeologists believe that Sekhemket's pyramid would have been larger than Djoser's had it been completed. Today, the site, which lies southwest of Djoser's complex, is mostly concealed beneath sand dunes and is known as the Buried Pyramid.

Khaba was the fourth king during the 3rd Dynasty. He is believed to have reigned a relatively brief four years between 2603 BC to 2599 BC, although these dates are highly conjectural, based on what scant evidence exists of this early king.

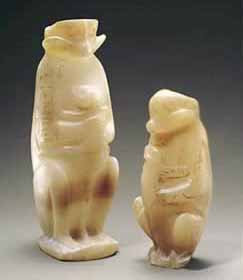

Khaba is commonly associated with the Layer Pyramid, located at Zawyet el'Aryan, about 4 km south of Giza. It is an unfinished pyramid whose construction is typical of Third Dynasty masonry and would have originally risen about 42-45m in height (it is now about 20m). While there were no inscriptions directly relating the pyramid to this king, a number of alabaster vessels inscribed with this king¹s name were discovered nearby in Mastaba Z-500 located just north of the pyramid.

Khaba is mentioned in the Turin King List as "erased", which may imply that there were dynastic problems during his reign, or that the scribe working on this list was unable to fully decipher the name from the more ancient records being copied from. It has also been suggested that Khaba may be the Horus name of the last king of the Third Dynasty, Huni, and that the two kings are the same person.

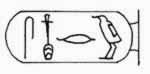

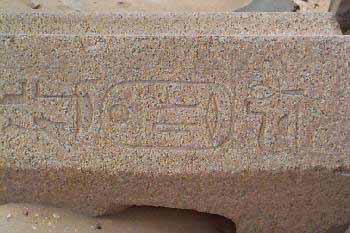

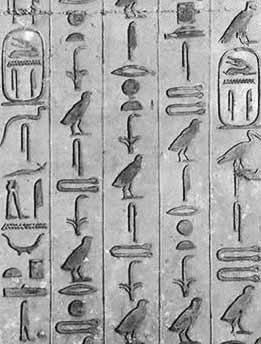

Khaba's name, typically displayed within a serekh rather than the more typical cartouche form established by the end of this dynasty, was written using the sign of a rising sun that had the sound value of kha, and a Saddle-billed Stork that had the sound value of ba.

Huni was the last Pharaoh of Egypt of the Third Dynasty.

Huni's wife Queen Meresankh I was the mother of Snefru. Huni was probably the father of Hetepheres, queen of the next king, Snofru.

While there is some confusion over kings and their order of rule near the end of the 3rd Dynasty, it is fairly clear who terminates the period and who also stood on the threshold between ancient Egypt's formative period and the grand courts of the Old Kingdom to follow. Huni paved the way for the great pyramid builders of the 4th Dynasty with his substantial construction projects and the possible restructuring of regional administration.

Yet, we really know very little about this king who ruled during a pivotal point in Egyptian history. The name Huni may be translated as "The Smiter". He is attested on monuments of his time by his nswt-bity name, written in a cartouche. Alternative readings have been suggested for his name, but none have been agreed upon, so he is typically called Huni even though it probably represents a corruption of his original name. He may also be one and the same as Horus Qahedjet, though this is uncertain.

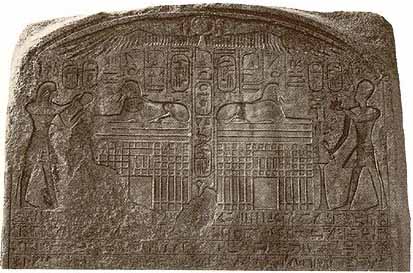

In the late 1960s, a limestone stela of unknown provenance was purchased by the Louvre museum. It was inscribed with the previously unknown Horus name, Qahedjet. The stela was important to Egyptian art historians because it depicts the earliest representation of a god (Horus) embracing the king. Therefore, it received considerable attention.

Though the stela is very similar in style to the relief panels of the Step Pyramid of Djoser, the execution of the carving is superior, and the iconography is more developed. Hence, Egyptologists tend to favor a date for the stela at the end of the 3rd Dynasty. Furthermore, the Horus name for the kings who Huni succeeded have been tentatively identified. Therefore, though with no certainty, some scholars believe Qahedjet to be the Huni's Horus name

The Turin Canon provides a reign for Huni of twenty-four years, and a shorter reign than this would appear unlikely given the scale of his completed building projects. His position as the last king of the 3rd Dynasty and Sneferu's immediate predecessor is confirmed by both the Papyrus Prisse and by the autobiographical inscription in the tomb of Metjen at Saqqara.

Actually, the most impressive monument which can be relatively clearly attributed to Huni is a small granite step pyramid on the island of Elephantine. It is now thought that a granite cone, bearing the inscription ssd Hwni, meaning "Diadem of Huni", and with the determinative of a palace originally came from Elephantine. It would seem therefore that Huni built either a palace or a building associated with the royal cult on this island.

This small pyramid, together with others of similar size and construction located at Seila in the Fayoum, Zawiyet el-Meitin in Middle Egypt, South Abydos, Tukh near Naqada, el-Kula near Hierakonpolis and in south Edfu, appear to be unique, both in their size and purpose. Many Egyptologists believe that, based on the monument at Elephantine, all but the Seila pyramid may be dated to the reign of Huni. Excavations have shown that his successor, Sneferu, was responsible for the pyramid at Seila.

Elephantine is an island in the River Nile, It measures some 1.2 km from north to south, and is about 400 m across at its widest. It is a part of the modern Egyptian city of Aswan.

There has been no small amount of debate about the purpose of these pyramids. Almost all of the major pyramids in Egypt, before and after Huni, were royal tombs of some nature. However, these small step pyramids appear to have little to do with funerary practices. Many scholars have suggested, though there is little proof, that they were constructed as cult places of the king or marked royal estates.

There was, for example, an administrative building attached to the pyramid at Elephantine. Their locations suggest that there could have been one such pyramid for each nome (ancient Egyptian province), at least in southern Upper Egypt. Some have even suggested that their construction might have been associated with the reorganization of regional government during Huni's reign. Irregardless, their purpose remains unclear without further evidence for their use.

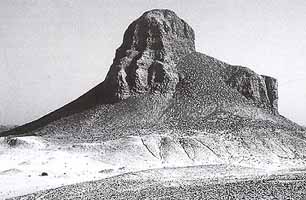

No one is certain about Huni's burial. It has been suggested that the pyramid at Maidum may have been his, and many Egyptologists seem certain that it was at least begun by him, though Middle and New Kingdom graffiti from the site credits Sneferu with its construction.

However, if Sneferu had a hand in this project, it is probable that he only finished the monument and converted it into a true pyramid. After all, Sneferu built at least two other large pyramids and was buried in one of these. Otherwise, Huni's burial remains a mystery. If he was not buried in the Maidum pyramid, than he may have been buried at Saqqara, though the only obvious location at that site, the unexcavated Ptahhotep enclosure to the west of the Djoser's complex, has no substructure. Hence, it is unlikely to be an unfinished step pyramid complex.

Some scholars theorize that the small step pyramids built by Huni somehow lessened the importance attached to the royal tomb. According to this view, Huni may never have constructed a pyramid tomb complex at all.

However, the general consensus seem to be that the Maidum Pyramid was indeed his, even though there is no evidence of there ever having been a stone sarcophagus in the subterranean burial chamber and therefore no clear evidence he was ever buried in this pyramid. Another theory suggests that he was actually buried in an unidentified mastaba number 17 on the northeast side of the pyramid, where there is a typical Old Kingdom, uninscribed granite sarcophagus.

Though we traditionally end the 3rd Dynasty with Huni, he was probably the father of the next King. It is though that the mother of Sneferu was probably Meresankh, who was either a lesser wife or concubine of Huni's. If so, Sneferu would have married his half sister, Hetepheres I, who was Huni's daughter. Little else is known about Huni's family relationships.

Huni's memory lived on for some time after his death, for the Palermo Stone lists an estate belonging to his cult during the reign of the 5th Dynasty King Neferirkara some 150 years after his death. This is really no surprise, for the achievements of Huni's reign are impressive, and he clearly ushered in the great culture of Egypt's Old Kingdom.

The structure of provincial government recorded in the tomb of Metjen probably signals a definitive break from the Early Dynastic past, and set the stage for the absolute central control of manpower and resources needed for the massive pyramid building of the 4th Dynasty.

The Fourth Dynasty

The Fourth Dynasty of Egypt was the second of the four dynasties considered forming the Old Kingdom. The pharaohs of this dynasty include some of the best-known kings of ancient Egypt known for constructing pyramids, perhaps the hallmark of Egypt. All of the kings of this dynasty commissioned at least one pyramid to serve as a tomb or cenotaph.

Like the Third Dynasty, these kings maintained their capital at Memphis.Sneferu, the dynasty's founder, is known to have commissioned three pyramids, and some believe he was responsible for a fourth. So although Khufu, his successor and son by Hetepheres I, erected the largest pyramid in Egypt, Sneferu had more stone and brick moved than any other pharaoh.

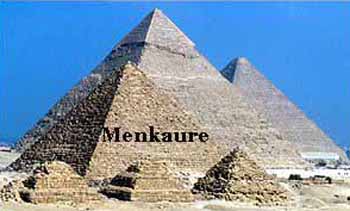

Khufu (Greek Cheops), his son Khafra (Greek Chephren), and his grandson Menkaura (Greek Mycerinus) all achieved lasting fame in the construction of their pyramids. To organize and feed the manpower needed to create these pyramids required a centralized government with extensive powers, and Egyptologists believe the Old Kingdom at this time demonstrated this level of sophistication.

Although it was once believed that slaves built these monuments, study of the pyramids and their environs have shown that they were built by a corvée of peasants drawn from across Egypt, who apparently worked while the annual Nile flood covered their fields.

While the pyramids suggest that Egypt enjoyed unparalleled prosperity during the Fourth Dynasty, they survived as a reminder to the inhabitants of the forced labor that created them, and these kings - Khufu in particular - were remembered as tyrants: first in the Papyrus Westcar, and millennia later in legends recorded by Herodotus (Histories, 2.124-133).

The archetype of the Turin King List, which otherwise records all of the names of the kings of this dynasty, has two names missing, which the scribe indicated with the Egyptian word wsf ("missing").

Sextus Julius Africanus reports Manetho had the names Bikheris and Tamphthis in those positions, while Eusebius does not mention either. Some authorities (such as K.S.B. Ryholt) follow Africanus in adding a possible Egyptian version of these names to the list; others omit them entirely.

The earliest known records of Egypt's contact with her neighbors are dated to this dynasty. The Palermo stone records the arrival of 40 ships laden with timber from an unnamed foreign land in the reign of Sneferu.

The names of Khufu and Djedefra were inscribed in gneiss quarries in the Western Desert 65 km. to the northwest of Abu Simbel; objects dated to the reigns of Khufu, Khafra, and Menkaura have been uncovered at Byblos and to the reign of Khafra even further away at Ebla, evidence of diplomatic gifts or trade.

It is unclear how this dynasty came to an end. Our only clue is that a number of Fourth Dynasty administrators are attested as remaining in office in the Fifth Dynasty under Userkaf.

Egyptian Fourth Dynasty Family Tree

First king of the 4th Dynasty

Sneferu, also spelt as Snefru or Snofru (in Greek known as Soris), was the founder of the fourth dynasty of Egypt, reigning from around 2613 BC to 2589 BC. While the Turin Cannon records the length of his reign as 24 years, graffiti in his northern (Red, and later) pyramid at Dahshur may suggest a longer reign.

His name, Snefer, means "To make beautiful" in Egyptian.

His Horus name was Nebmaat, but his royal titulary was the first to have his other name, Snefru, enclosed within a cartouche.

It was by this "cartouche name" that he and subsequent kings were best known. He enjoyed a very good reputation by later generations of ancient Egyptians. Considered a benign ruler (highly unusual), the Egyptian term, snefer can be translated as "to make beautiful".

Snefru was most likely the son of Huni, his predecessor, though there seems some controversy to this, considering the break in Dynasties. However, his mother may have been Meresankh I, who was probably a lessor wife or concubine and therefore not of royal blood. Hence, this may explain what prompted the ancient historian, Manetho (here, Snefru is known by his Greek name, Soris), to begin a new dynasty with Snefru. However, it should be noted that both the royal canon of Turin and the later Saqqara List both end the previous dynasty with Huni.

Snefru was almost certainly married to Hetepheres I, who would have been at least his half sister, probably by a more senior queen, in order to legitimize his rule. She was the mother of his son, Khufu, who became Egypt's best known pyramid builder, responsible for the Great Pyramid at Giza.

It is believed he had at least three other wives who bore him a number of other sons, including his eldest son, Nefermaet, who became a vizier. He probably did not outlive his father, so was denied the Egyptian throne. Other sons include Kanefer, another vizier who apparently continued in this capacity under Khufu (Cheops). We also believe he fathered several other sons, and at least several daughters.

In reality, Snefru may probably be credited with developing the pyramid into its true form. He apparently began by build what was probably a step pyramid at Maidum (Madum), which was later converted into a true pyramid. But this effort met with disaster (though probably not a quick one), because of the pyramid's mass and steep slope.

He also built the Red Pyramid and Bent Pyramid at Dahshur. The Bent Pyramid was the first true pyramid planned from the outset, while the Red Pyramid is the first successful true pyramid built in Egypt. The Red and Bent Pyramids are, respectively, the third and fourth largest pyramids known to have been built in Egypt.

In addition, Snefru is credited with at least one of a series of "regional" or provincial pyramids, at Seila. This is a small, step pyramid with no substructure. A number of other similar pyramids dot the Egyptian landscape, as far south as Elephantine Island, and some Egyptologists believe Snefru (or his father) may be responsible for all, or at least some of these. No one is very certain of the purpose of these small pyramids, but they were likely either associated with provincial cult worship of the king, or may have been located near to the king's "rural" palaces.

In many respects, including the combined scale of building projects and the evolutionary architectural achievements, Snefru must be ranked as one of Egypt's most renowned pyramid builders. In fact, the sheer volume of building work was greater than any other ruler in the Old Kingdom.

However, his achievements in pyramid building extended beyond the pyramid structure itself, and obviously incorporated evolving religious beliefs. During his reign, we see the first real elements of the sun worship that was to follow and reach a culmination over a thousand years later in the reign of Akhenaten.

For the first time in the orientation of the building plan the main axis was oriented from east to west rather than north to south, as were earlier pyramids. This was apparently a move away from the astronomical "star" oriented beliefs, toward the east-west passage of the sun and the worship of Ra. Now, with Snefru, the mortuary temple is on the east rather than than on the north side like in the Djoser Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara. Furthermore, we see the first of the small satellite pyramids placed near the southern face of the main pyramid, a structure that we still do not completely understand today. Furthermore, the pyramid and mortuary temple elements were now linked by a causeway to a valley temple located on the edge of the cultivation closer to the Nile. It is believed the valley temple operated as a monumental gateway to the whole of the pyramid complex.

While the growing importance of the sun worship is obvious in Snefru's reign, the worship of Osiris was probably also beginning to influence Egyptian religion, though little in the way of documented evidence can be supplied. With all of Snefru's building activities, it is not surprising that he was very active in the quarries. His name has been found attested to in rock inscriptions at the turquoise and copper mines of the Wadi Maghara in the Sinai peninsula, as well as other quarries.

Snefru is also credited with keeping the administrative power of the country within the royal family, As stated above, two of his sons became viziers and it is likely that many other royal children held important posts. By the end of the 6th Dynasty, administrative power within Egypt would be greatly decentralized which is considered at least one of the reasons Egypt fell into the chaos of the First Intermediate Period. Generally, Egypt was most powerful and prosperous when Egyptian rulers maintained a strong central government, like that of Snefru's. In order to further facilitate this centralized power base, he also apparently reorganized land ownership among his nobles, presumably to prevent them from becoming too powerful, but also to stimulate the cultivation of marshlands.

According to the Palermo Stone, he campaigned militarily against the Nubians and Libyans. The expedition to Nubia was a very large campaign. The Palemo Stone records a booty of 7,000 captives and 200,000 head of cattle. The population of Nubia was never very great, so this was perhaps a rather substantial depopulation of the area. Not only were these campaigns against Nubia initiated to obtain raw material and goods, but also to protect Egypt's southern borders as well as the all important African trade routes. The campaign in Libya records 11,000 captives and 13,100 head of cattle.

The Palermo Stone also provides a record of forty ships that brought wood (probably cedar) from an unnamed region, but perhaps Lebanon. Among other building uses, Snefru is credited as has having used some of this wood to build Nile river boats up to about 50 meters (about 170 ft.) in length.

It is interesting to note that Snefru's later deification was perhaps partially due to his status as an "ideal" king, who's deeds were emulated by later kings to justify their legitimacy to the throne. His reputation was no doubt enhanced by the Westcar Papyrus (now in Berlin), probably written during the Hyksos period. Yet, even though considered a warlike king by many, his worship in the Middle Kingdom was just as much fueled by the admiration of common Egyptians (according to traditional history).

Ancient literature repeatedly depicts him as a ruler who would address common Egyptians as "my friend", or "my brother". It is also not surprising that during the Middle Kingdom, his cult was particularly strong among the Sinai miners. Because of his massive building projects, considerable resources from Snefru's reign were employed to develop those quarries.

Therefore, Snefru became especially associated with this quarry district. Certainly Snefru had a number of choices for his burial, but we believe he was actually interred in the Red Pyramid at Dahshure. There, in the 1950s, the remains of a mummy were found of a man past middle age, but not much so, suggesting that the king may have come to rule Egypt at a fairly early age.

Some Egyptologists continue to attribute the Madium Pyramid to Huni (or more properly, Nysuteh), as well as possibly to Horus Qahedjet (2637-2613 BC). However, even these scholars appear to believe that Snefru finished this pyramid, but it would have been highly unusual for a ruler of Egypt to have made such a substantial contribution to his predecessor's mortuary complex. Still the question of who actually started the construction of this pyramid is a mater for future discovery.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

Second king of the 4th Dynasty

He was allegedly the builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza - the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing - and founder of the Giza Plateau near modern Cairo and Memphis. He reigned from around 2589 BC to 2566 BC.

Unlike his grandfather Huni, and his father Sneferu, both of whom were remembered as benevolent and compassionate rulers, Khufu was reported by Herodotus to have been a cruel despot.

KhufuÐs Horus name was Medjedu, and his full birth-name was Khnum-Khufu, meaning, "the god Khnum protects me." Khnum was considered the local god of Elephantine, near the first Nile cataract, who created mankind on his "potterÐs wheel" and was also responsible for the proper flooding of the Nile.

Khufu may have been already on in years when he took the throne. His kinsman and vizier, Hemiunu, was also the architect of the Great Pyramid. KhufuÐs senior wife was named Merityotes, and she and his other two wives were each buried in one of the three smaller subsidiary pyramids that lie just south of the mortuary temple of the main pyramid.

Khufu may have been already on in years when he took the throne. His kinsman and vizier, Hemiunu, was also the architect of the Great Pyramid. KhufuÐs senior wife was named Merityotes, and she and his other two wives were each buried in one of the three smaller subsidiary pyramids that lie just south of the mortuary temple of the main pyramid.

Khufu had several sons, among them Kawab, who would have been his heir, Khufukhaf, Minkhaf, and Djedefhor, Djedefre and Khephren or Khafre. The so-called Papyrus Westcar contains tales of some of these sons.

Though the Great Pyramid somehow represents the very essence of "ancient Egypt," the King for whom it was built as a tomb has left little recorded information of his actual reign. Khufu probably reigned for 23 or 24 years. There is evidence that he sent expeditions to the Sinai, and worked the diorite stone quarries deep in the Nubian desert, north-west ofAbu Simbel.

Inscriptions on the rocks at Wadi Maghara record the presence of his troops there to exploit the turquoise mines, and a very faint inscription at Elephantine indicates that he probably mined the red granite of Aswan as well.

Herodotus, who wrote his histories and commentaries on Egypt around 450 BCE, centuries after Khufu had reigned around 2585 BCE, recorded this about the King: Kheops brought the country into all kinds of misery. He closed the temples, forbade his subjects to offer sacrifices, and compelled them without exception to labor upon his works the Egyptians can hardly bring themselves to mention Kheops so great is their hatred.

It was even said that Khufu set one of his daughters into a brothel so that she could raise revenue to build the pyramid, also asking each client for a block of stone so she could build her own pyramid. No evidence exists for such a story, though there are smaller pyramids which probably belonged to half-sister/wives of Khufu, and he did have at least three daughters of record.

Even prior to Herodotus, the author of the document now known as the Papyrus Westcar depicts Khufu as cruel. The text was inscribed in the Hyksos period prior to the 18th Dynasty, though its composition seems to date from the 12th Dynasty. One story, Kheops and the Magicians, relates that a magician named Djedi who can reputedly bring back the dead to life. He is presented to Khufu, who orders a prisoner brought to him, so that he  may see a demonstration of the magician's talents.

may see a demonstration of the magician's talents.

Khufu further orders that the prisoner should be killed, and then Djedi can bring him back to life. When Djedi objects, the King relents his initial decision, and Djedi then demonstrates his talent on a goose.

It should be noted that while Khufu has acquired this reputation, accurate or not, the years and labor that went into building his Pyramid tomb was surpassed by the three pyramids built by his father Sneferu, who was contrarily remembered as an amiable ruler.

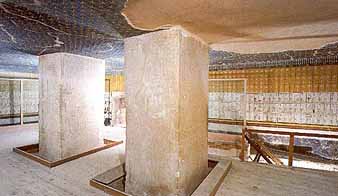

The Great Pyramid originally stood 481 feet high complete with its original casing, but since it lost its top 30 feet, it stands only 451 feet now. It covers about 13 acres. The exterior casing was shining white limestone, laid from the top downwards. It was largely robbed in the Middle Ages to build medieval Cairo. Nothing now remains of the limestone mortuary temple, which was 171 feet by 132 feet, except its black basalt floor. The complexÐs valley temple has disappeared under the Arab village, though traces of this temple could be seen when new sewer systems were being laid down.

Along with the pyramid itself, the remains of a magnificent 141-foot long ship of cedar wood had also been found in a rock-cut pit close to the south side of the Great Pyramid. A second ship may also rest in a second sealed pit, though not in as good condition as this first. The ship was restored over many years, and now lies in a special museum built near the pyramid itself. The ship may have symbolized the solar journey of the deceased king with the gods, particularly the sun-god Ra.

Along with the pyramid itself, the remains of a magnificent 141-foot long ship of cedar wood had also been found in a rock-cut pit close to the south side of the Great Pyramid. A second ship may also rest in a second sealed pit, though not in as good condition as this first. The ship was restored over many years, and now lies in a special museum built near the pyramid itself. The ship may have symbolized the solar journey of the deceased king with the gods, particularly the sun-god Ra.

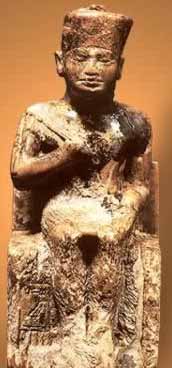

It is ironic indeed that for all the magnificence of his pyramid, his funeral boat, and the wonders of the funerary furnishings that were discovered belonging to his mother, Queen Hetepheres, wife to Sneferu, the only portrait we have of Khufu is a tiny 3-inch high statue sculpted in ivory.

I t may have been once easy to contemplate the builder of such a monument as the Great Pyramid to have virtually enslaved his people to accomplish it, and to order a royal princess to prostitute herself. Sneferu, Khufu's father, had three separate pyramids built during his reign. Surely the workmen or nobles would have left some evidence of their dissatisfaction at least at the whimsicality of their sovereign if not his despotism. Yet Sneferu is remembered as amiable and pleasure-loving.

And Khafre, Khufus son, left not only a pyramid but quite possibly a Sphinx as well. And history, or at least, historians, do not record Khafre is being a despot.

Continuing work at Giza is further showing that the men responsible for the building of the pyramids led normal lives. They baked bread, ate fish, made offerings to their blessed dead and the gods, and cared for their families.

They left funerary stelae and tombs behind to give us an indication of how they considered their lot. It is more likely that the Greeks could less easily conceive of such a project of long-term labor as being anything but forced. Perhaps some archaeologist millennia in our own future may find rusted iron skeletons of some of our finest skyscrapers and wonder to what cruel overlords we owed the sweat of our own forced labor.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

Third king of the 4th Dynasty

The Egyptian pharaoh Djedefra was the successor and son of Khufu. The mother of Djedefra is unknown.

He married his (half-) sister Hetepheres II, which may have been necessary to legitimize his claims to the throne if his mother was one of Khufu¹s lesser wives.

He also had another wife, Khentet-en-ka with whom he had (at least) three sons, Setka, Baka and Hernet and one daughter, Neferhetepes.

The Turin King List credits him with a rule of eight years, but the highest known year referenced to during this reign was the year of the 11th cattle count. This would mean that Djedefra ruled for at least eleven years, if the cattle counts were annual, or 21 years if the cattle counts were biennial.

He was the first king to use the title Son of Ra as part of his royal titulary, which is seen as an indication of the growing popularity of the cult of the solar god Ra.He continued the move north by building his (now ruined) pyramid at Abu Rawash, some 8 km to the North of Giza.

It is the northernmost part of the Memphite necropolis.

In 2004, evidence that Djedefra may have been responsible for the building of the Sphinx in the image of his father was reported by French Egyptologist Vassil Dobrev.

Chephren - Suphis II - Appearing Like Re - (2558 BC - 2532 BC)

Fourth king of the 4th Dynasty.

His birth name was Khafre, which means "Appearing like Re". He is also sometimes refereed to as Khafra, Rakhaef, Khephren or Chephren by the Greeks, and Suphis II by Manetho. He was possibly a younger son of Khufu (Cheops) by his consort, Henutsen, so he was required to wait out the reign of Djedefre, his older brother, prior to ascending to the throne of Egypt. However, there is disagreement on this matter. There is no agreement on the date of his reign; some authors saying it was between 2558 BC and 2532 BC; this dynasty is commonly dated ca. 2650 BC2480 BC.

Identifying him with Suphis II, Manetho gives his reign as lasting 66 years, but this certainly cannot be substantiated. Modern Egyptologists believe he may have ruled Egypt for a relatively long period, however, of between the 24 years ascribed to him by the Turin Royal Cannon papyrus (which was apparently confirmed by an inscription in the mastaba tomb of Prince Nekure), and 26 years. He is thought to have ruled Egypt from about 2520 to 2494 BC.

There are rumors of a problem with the succession of Khafre. Some authorities maintain that Djedefre may have even stole the throne, perhaps as a younger brother of Khafre, and that Khafre may have even murdered him.

Much of this speculation originates from the fact that Djedefre broke with the Giza burial tradition, electing instead to locate his tomb (pyramid) at Abu Rawash. However, there is little real evidence to support such a conclusion, and in fact, Khafre continued Djedefre's promotion of the cult of the sun god Re by using the title the 'Son of the Sun' for himself and by incorporating the name of the god in his own.

It is clearly evident from the fine mastaba tombs of the nobles in his court that Egypt was prosperous while Khafre held the throne. Carved on the walls of the tomb of Prince Nekure, a "king's son", was a will to his heirs. It is the only one of its kind known from this period, and in it he leaves 14 towns to his heirs, of which at least eleven are named after his father, Khafre.

Though his legacy was divided up among his five heirs, 12 of the towns were earmarked to endow the prince's mortuary cult.We do know that Khafre participated in some foreign trade, or at least diplomacy, for objects dating from his reign have been found at Byblos, north of Beirut, as well as at Tell Mardikh (Ebla) in Syria. He apparently also had diorite quarried at Tashka in Nubia and probably sent expeditions into the Sinai.

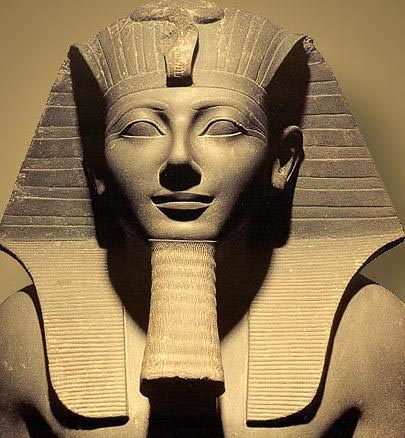

Though there are few inscriptions left for us to completely understand the era of Khafre's rule, he did leave behind some of the most important treasures ancient Egypt has to offer.

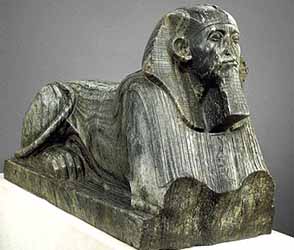

Besides his pyramid complex at Giza, most Egyptologists believe he also built the Great Sphinx and that it is his face that adorns this huge statue, which sits just beside his valley temple.

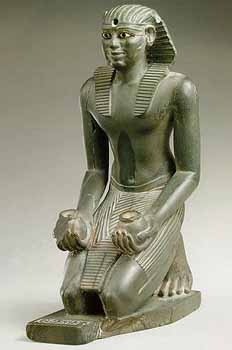

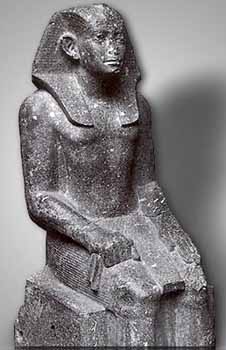

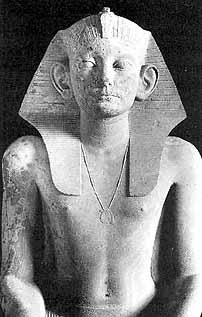

In addition, the life size diorite statue of Khafre found in his valley temple and now located in the Egyptian Antiquities Museum is one of the most magnificent artifacts ever discovered.

Like his father Khufu, Khafre was depicted in fold tradition as a harsh, despotic ruler. Though as late as the New Kingdom, Ramesses II seems to have had no qualms about taking some of the casing from his pyramid at Giza for use in a temple at Heliopolis, by Egypt's Late Period, the cults of the fourth dynasty kings had been revived, and Giza became a focus of pilgrimage.

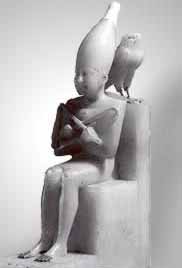

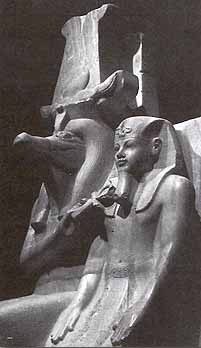

Khafre's mummy has been lost, but his mortuary temple at Giza yielded one of the finest extant Old Kingdom statues an almost undamaged life-size seated diorite figure of the king enjoying the protection of the god Horus. A statue of Khafre under the protective shadow of a falcon is in the Cairo Museum.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

Fifth king of the 4th Dynasty

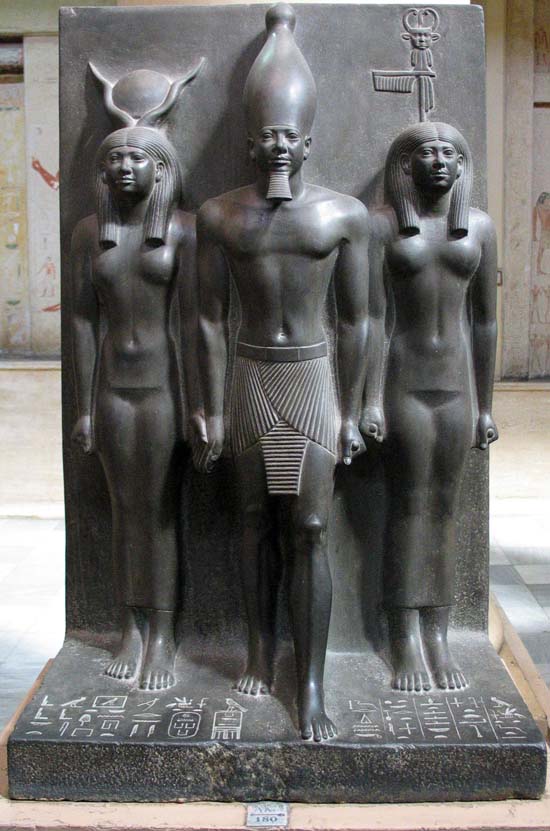

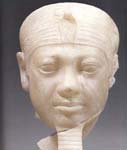

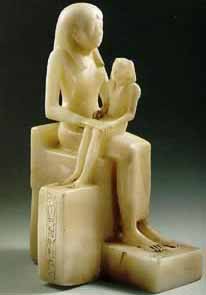

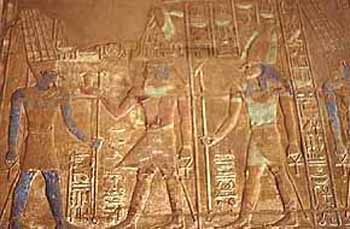

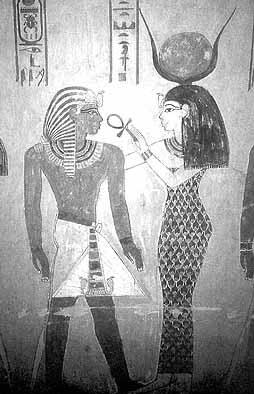

Menkaure with his wife Khamerernebty II

appearing as Hathor (left) and the goddess

of the seventeenth nome of Egypt (right)

Menkaure is the son of Khafre and the grandson of Khufu of Dynasty IV. He bore the titles Kakhet and Hornub. There are doubts that Menkaure could be the son of Khafre, because the Turin Papyrus mentioned a name of a king between Menkaure and Khafre, but the name was smashed. A Middle Kingdom text written on a rock at Wadi Hamamat includes the names of the kings: Khufu, Djedefre, Khafre, Hordedef and Bauefre. This text indicates to some that Hordedef and Bauefre ruled after Khafre. But it seems that their names were not written as kings because Menkaure's names were not mentioned. It has been suggested that Hordedef's name was mentioned because was a wise educated man in this period and perhaps Bauefre was a vizier.

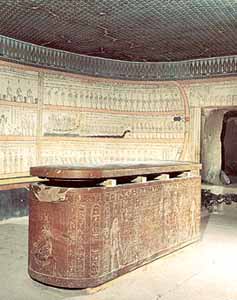

He built the smallest pyramid at the Giza plateau, and is called Menkaure is Divine. Menkaure's pyramid is two-tone in color: the top half covered with bright white limestone casing, while red Aswan granite was used for the casing on the bottom. E1-Makrizi, the Arab historian named Menkaure's pyramid as the colored pyramid because of the red granite casing. The pyramid stands 66.5m high, which is much smaller than the other two pyramids at Giza. The pyramid is remarkable because it is the only pyramid in Dynasty IV that was cased in 16 layers of granite, Menkaure planned to cover the surface with granite but he could not because of his sudden death.

The pyramid complex of Menkaure was completed by his son and successor Shepseskaf but the temples has architectural additions which were made during Dynasties V and VI. This suggests that the cult of Menkaure was very important and perhaps differed from the cults of Khufu and Khafre. Shepseskaf completed the pyramid complex with mudbrick and left an inscription inside the Valley Temple indicating that he built the temple for the memory of his father.

At the pyramid's entrance, there is an inscription records that Menkaure died on the twenty-third day of the fourth month of the summer and that he built the pyramid. It is thought that this inscription dates to the reign of Khaemwas, son of Ramsses II. The name of Menkaure found written in red ochre on the ceiling of the burial chamber in one of the subsidiary pyramids.

When pyramid was explored in the 1830's, a lidless basalt sarcophagus was found in the burial chamber. Inside it was a wooden mummiform coffin inscribed with Menkaure's name. This is curious because mummiform coffins weren't made until much later. Best guess is that the coffin was provided in an attempted restoration during the 26th dynasty (that's 2000 years later!) when there was a renewed interest in the culture of the Old Kingdom.

The wooden coffin and basalt sarcophagus were sent on separate ships to England to end up on display in the British Museum, but a storm at sea sank the boat that was transporting the sarcophagus. It sank to the bottom of the sea and was never recovered.

The sarcophagus was allegedly lost in the Mediterranean between ports of Cartagena and Malta when the ship 'Beatrice' sank after setting sail on October 13, 1838. There still exists the wooden anthropoid coffin found inside the pyramid which bears the name and titles of Menkaure.

Menkaure's main queen was Khamerernebty II, who is portrayed with him in a group statue found in the Valley Temple. It is believed that she is buried in Giza.

Menkaure ruled for 18 years. There are two inscriptions found in his pyramid complex. The first was a decree bearing the Horus name of Merenre of Dynasty VI. The decree stated that the Valley Temple was in use until the end of the Old Kingdom. The objects found in some of the storage rooms of the temples show that the king's cult was maintained and that the temple had a dual function as a temple and a palace.

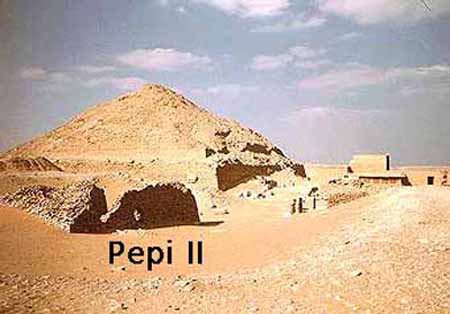

The second decree of Pepi II was found on the lower temple vestibule, awarding privileges to the priests of the pyramid city. In the adjacent open court and in the area just east of the temple lie the remains of the Old Kingdom houses. Pepi II's decree indicates that these houses belonged to the pyramid city of Menkaure. Here lived the personnel responsible for maintaining the cult of the deceased king.

The statuary program found inside the complex displays the superb quality of arts and crafts. The triads in Menkaure's valley temple suggest that his pyramid complex was dedicated to Re, Hathor, and Horus. In addition, they show the king's relationship with the gods and are essential to his kingship, indicating both a temple and palace function.

The textual evidence indicates that the high officials had more privileges in his reign that in any other period. They had many statues in their tombs; the inscriptions and the scenes increased and were set on rock-cut tombs. In the tomb of Debhen an inscription was found describing the kindness of Menkaure.

When Debhen came to visit the king's pyramid, he asked the king for permission to build his tomb near the pyramid. The king agreed and even ordered that stones from the royal quarry in Tura should be used in building his tomb. The text also mentions that the king stood on the road by the Hr pyramid inspecting the other pyramid. The name "Hr" was also found written in the tomb of Urkhuu at Giza, who was the keeper of a place belonging to the Hr pyramid. It is not clear what the Hr pyramid is. Is it a name of a subsidiary pyramid, or the name of the plateau? The Debhen texts is a revelation of how the king tried to inspire loyalty by his people giving them gifts.

Menkaure also had a new policy - he opened his palace to the children of his high officials. They were educated and raised with the king's own children. Shepsesbah is one of those children. The textual and archaeological evidence of the Old Kingdom indicates that the palace of the king was located near his pyramid and not at Memphis. Menkaure explored granite from Aswan and he sent expeditions to Sinai. Excavations under the author revealed a pari of statues of Ramses II on the south side of Menkaure's pyramid. The statues were made of granite, and one represents Ramses as king while the other as Atum-Re.

The name of Menkaure was found written on scarabs dated to the 26th Dynasty, which may imply that he was worshipped in this period.

Herodotus mentioned that Menkaure died suddenly and added that there was an oracle from the Buto statue that foretold that he would live for 6 years. Menkaure started to drink, and enjoy every moment of his remaining years. However, Menkaure lived for 12 years, thus disproving the prophecy. Herodotus also said that his daughter committed suicide.

The Greek historian also wrote that the Egyptians loved Menkaure more than his father and grandfather. The Late Period tales were based on Menkaure's reputation during the Old Kingdom. He ruled with justice, gave freedom to his officials to carve statues and make offerings, and stopped the firm rules.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

Shepseskaf was the sixth king of the 4th Dynasty.

Pharaoh Menkaure has died after a 28 year long reign. His son and heir by queen Khamerernebty II, the young Prince Khuenre, has tragically died before he could take to the throne. Menkaure is therefore succeeded by Shepseskaf, a son of Menkaure by an unknown minor wife. Although a half brother to Prince Khuenre, he was not an ideal choice for the role of Pharaoh, as he is not of complete royal blood.ð

His major wife was Bunefer. He has no known sons and one daughter, Khamaat.

He was in power for just a short period of time. This was another difficult political period, during which there were many confrontations with various priests. Many desired independence and rebelled against Shepseskaf's authority.

Shepseskaf completed his father Menkaure's Pyramid. He chose not to be buried in a Pyramid and as he returned to Saqqara after most of his 4th Dynasty predecessors had either preferred Dashur in the South (Snofru) or Abu Rawash (Djedefre) and Giza (Kheops, Khefren and Mykerinos) in the North to build their funerary monuments. This return to Saqqara has often been interpreted more as a distancing of Giza and of the supposedly oppressive politic followed by Kheops and Khefren, but there are, in fact, no valid arguments that support this theory.

Whatever Shepseskaf's motivations for returning to Saqqara may have been, it is perhaps also telling that he moved to an area in Saqqara that does not appear to have been used before: Saqqara-South. In fact, his tomb is the southern-most royal tomb of Saqqara.

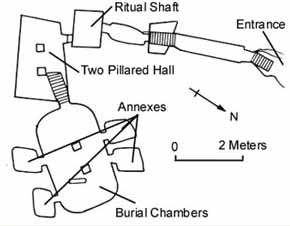

Even in the choice of his funerary monument, Shepseskaf chose not to follow the standard established by his ancestors. His tomb consists of a mastaba-shaped superstructure with a small mortuary temple to the east. No satellite or queen's pyramids appear to have been built.

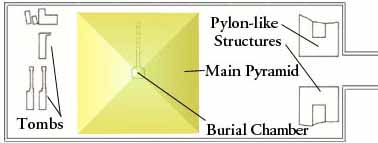

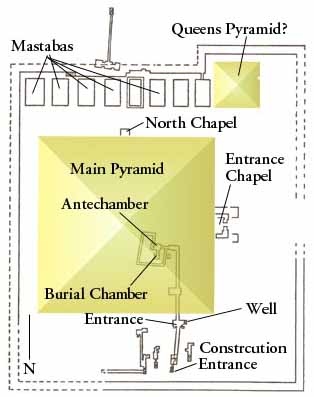

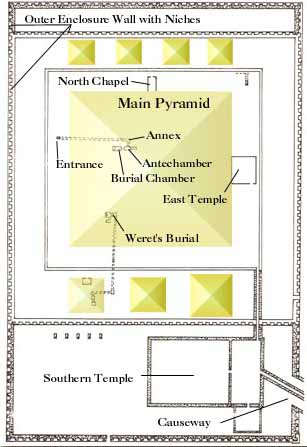

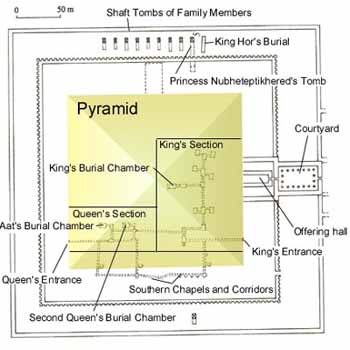

Map of the tomb and temple of Shepseskaf.

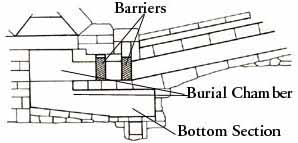

The mastaba, which has earned this monument the name Mastabat el-Fara'un, was 99.6 metres long and 74.4 metres broad. It was originally encased in limestone, except for its base course, which was in granite. It had a slope of 70 E and certainly was shaped like a shrine: a rounded top flanked by two almost vertical walls.

Cut-away of the Mastabat el-Fara'un showing

the original shape of this rather unique royal tomb.

Source: Lehner, Complete Pyramids, p. 139

The mastaba is entered from the north side, from where a corridor descends for 20.95 metres with a slope of 23É30'. At the end of the passage is a horizontal corridor passage followed by a second passage blocked by three portcullises and an antechamber. A short passage to the west goes down into the vaulted burial chamber that measures 7.79 by 3.85 metres and has a height of 4.9 metres. Fragments of the sarcophagus indicate that it was made of a hard dark stone and decorated like Mykerinos'. To the south of the antechamber a corridor extends with 6 niches to the east, again similar to the niches found in the pyramid of Mykerinos.

The mastaba is enclosed within two mudbrick walls: the first also incorporates a small mortuary temple that had some open courts, an offering hall and a false door, flanked by 5 magazines. The long causeway that extended towards the east has not (yet) been excavated.

After Shepseskaf died, Khentkawes, another child of Menkaure by a minor wife and Shepseskaf's half-sister, married a nobleman named Userkaf, who was the great grandson of Pharaoh Khufu. Upon his marriage to Pharaoh Shepseskaf's half sister Khentkawes, Userkaf was in a strong enough position to be crowned Pharaoh over all Egypt, and begin the 5th Dynasty of Kings.

Userkaf returned to the more traditional pyramid-tomb. From then on, the dimensions and shape of the pyramid, and the temple connected to it, would become more and more standardized.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

Djedefptah is a shadowy figure, and his existence is questionable. It is usual to consider Shepseskaf to be the last pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty. Manetho however lists a king Tamphthis (this may probably a corrupted form of ptah-djedef), and notes that he reigned for 9 years.

The Turin Canon has an unnamed pharaoh after Shepseskaf who ruled for about two years, and this ruler may be Djedefptah. Very little else is known about him, although he may have been a son of Shepseskaf.

The Fifth Dynasty

The Fifth Dynasty of Egypt is considered part of the Old Kingdom of ancient Egypt. Manetho writes that these kings ruled from Elephantine, but archeologists have found evidence clearly showing that their palaces were still located at Ineb-hedj ("White Walls").

How Pharaoh Userkaf founded this dynasty is not known for certain.

The Papyrus Westcar, which was written during the Middle Kingdom, tells a story of how king Khufu of the Fourth Dynasty was given a prophecy that triplets born to the wife of the priest of Ra in Sakhbu would overthrow him and his heirs, and how he attempted to put these children - named Userkaf, Sahura, and Neferirkara - to death; however in recent years, scholars have recognized this story to be at best a legend, and admit their ignorance over how the transition from one dynasty to another transpired.

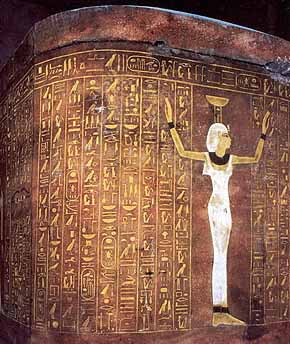

During this dynasty, Egyptian religion made several important changes. The earliest known copies of funerary prayers inscribed on royal tombs (known as the Pyramid Texts) appear.

The cult of the god Ra gains added importance, as kings from Userkaf through Menkauhor built temples dedicated to Ra at or near Abusir.

Then late in this dynasty, the cult of Osiris assumes importance, most notably in the inscriptions found in the tomb of Unas.

Amongst non-royal Egyptians of this time, Ptahhotep, vizier to Djedkare Isesi, won fame for his wisdom; The Maxims of Ptahhotep was ascribed to him by its later copyists.

Non-royal tombs were also decorated with inscriptions, like the royal ones, but instead of prayers or incantations, biographies of the deceased were written on the walls.

As before, expeditions were sent to Wadi Maghara and Wadi Kharit in the Sinai to mine for turquoise and copper, and to quarries northwest of Abu Simbel for gneiss.

Trade expeditions were sent south to Punt to obtain malachite, myrrh, and electrum, and archeological finds at Byblos attest to diplomatic expeditions sent to that Phoenician city.

Finds bearing the names of a several Fifth Dynasty kings at the site of Dorak, near the Sea of Marmara, may be evidence of trade but remain a mystery.

Userkaf was the founder and first king of the 5th Dynasty.

It is believed that he was father of two pharaohs, Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai, who both succeeded him to the throne. Another less common view, in concordance with a story of the Westcar Papyrus, is that first three rulers of the Fifth dynasty were all brothers, the sons of queen Khentkaus I. He is given a reign of 7 Years by both the Turin King List and Manetho.

His pyramid complex at Saqqara introduced several new changes from the previous dynasty. In comparison with the tombs of the Fourth dynasty, his pyramid was rather small. Instead, increased focus was put on the mortuary temple, which were more richly decorated than in the previous Fourth dynasty. In the temple courtyard, a colossal statue of the king was raised. The mortuary temple was to the south of the pyramid, not to the east, as was traditional. This is now seen as being due to the increasing importance of the sun god in the south, the temple would be bathed in the sun's rays throughout the day.

Userkaf, as the originator of the fifth dynasty, clearly felt he should associate himself with one of his great predecessors. To achieve this, he build his pyramid complex at Saqqara, as close as possible to that of Djoser. When completed, the pyramid was 161 ft (49 m) high and encased in limestone, though the core was sloppily built and therefore crumbled when this casing was removed by robbers. Although the complex is now ruined and largely inaccessible, limited excavations there have produced a huge pink granite head of Userkaf. Userkaf also built the first of the Solar Temples of Abu-Gurob.

Reference: The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt Ian Shaw, 2000

The second king of the 5th Dynasty.

Sahure was a son of queen Khentkaus I, who, in her tomb at Giza, is said to have been the "mother of two kings". His father probably was Userkaf.

There are no wives or children known to him and at least no children of his seem to have outlived him, since he was succeeded by his brother, Neferirkare, the first king known to have used separate names.

His Horus name was Nebkhau.

It is believed he ruled Egypt from around 2487 BC to 2475 BC. The Turin King List gives him a reign of twelve years. The Palermo stone notes seven cattle counts, which would indicate a reign of at least 13 years if the cattle counts were held biannualy (every two years) as this Annal document indicates for the early Fifth Dynasty period.

It is probable that Khentkaus I was the character of Redjedet in the Papyrus Westcar, who according to the magician Djedi, was destined to give birth to the children of Ra and the first kings of the 5th Dynasty. But if Khentkaus I was his mother, a scene in her tomb at Giza showing her with the royal uraeus and beard might indicate that she may have acted as a regent for Sahure.

Most foreign relations during the reign of Sahure were economic, rather than combative. In one scene in his pyramid, we find great ships with Egyptians and Asiatics on board. It is believed they are returning from the port of Byblos in Lebanon with huge cedar trees. For this, we have corraborating evidence in the form of his name on a piece of thin gold stamped to a chair, as well as other evidence of Fifth dynasty king's cartouches found in Lebanon on stone vessels. Other scenes in his temple depict what we are told are Syrian bears.

We also have the first documented expedition to the land of Punt, which apparently yielded a quantity of myrrh, along with malachite and electrum, and because of this, Sahure is often credited with establishing an Egyptian navy. There are also scenes of a raid into Libya which yielded various livestock and showed the king smiting the local chieftains. The Palermo stone also corroborates some of these events and also mentions expeditions to the Sinai and to the exotic land of Punt, as well as to the diorite quarries northwest of Abu Simbel, thus, far into Nubia.

However, this same scene of the Libyan attack was used two thousand years later in the mortuary temple of Pepi II and in a Kawa temple of Taharqa. The same names are quoted for the local chieftain. Therefore, we become somewhat suspicious of the possibility that Sahure was also copying an even earlier representation of this scene.

He apparently built a sun temple, as did most of the 5th Dynasty kings. Its name was Sekhet-re, meaning "the Field of Re", but so far its location is unknown. We know of his palace, called Uetjesneferusahure ("Sahure's splendor soars up to heaven"), from an inscription on tallow containers recently discovered in Neferefre's mortuary temple. It may have been located at Abusir as well. We also know that under Sahure, the turquoise quarries in the Sinai were worked (probably at Wadi Maghara and Wadi Kharit), along with the diorite quarries in Nubia.

Sahure is further attested by a statue now located in New York's Museum of Modern Art, in a biography found in the tombs of Perisen at Saqqara and on a false door of Niankhsakhment at Saqqara, and is also mentioned in the tombs of Sekhemkare and Nisutpunetjer, kings of the Twelfth dynasty at their tombs in Giza.

His pyramid complex was the first built at the new royal burial ground at Abusir a few kilometres north of Saqqara (though Userkaf had probably already built his solar temple there) and marks the decline of pyramid building, both in the size and quality, though many of the reliefs are very well done.

His pyramid provides us most of the information we know of this king. The reliefs in his mortuary and valley temple depict a counting of foreigners by or in front of the goddess Seshat and the return of a fleet from Asia, perhaps Byblos. This may indicate a military interest in the Near East, but the contacts may have been diplomatic and commercial as well. As part of the contacts with the Near East, the reliefs from his funerary monuments also hold the oldest known representation of a Syrian bear.

When it was excavated in the first years of the 1900s, a great amount of fine reliefs were found to an extent and quality superior to those from the dynasty before. Some of the low relief-cuttings in red granite are masterpieces of their kind and still in place at the site. The construction of the pyramid was on the other hand (like the others from this dynasty) made with an inner core of roughly hewn stones in a step construction held together in many sections with a mortar of mud.

While this was under construction a corridor was left into the shaft where the grave chamber was erected separately and later covered by leftover stone blocks and debris. This working strategy is clearly visible from two unfinished pyramids and was the old style from the Third dynasty now coming back after being temporary abandoned by the builders of the five great pyramids at Dahshur and Giza during the Fourth dynasty.

Few depictions of the king are known, but in a sculpture he is shown sitting on his throne with a local nome deity by his side.

Today only the inner construction remains partly visible in a pile of rubble originating from the crude filling of debris and mortar behind the casing stones taken away a thousand years ago. The whole inner construction is badly damaged and not possible to access today.

The entrance at the north side is a short descending corridor lined with red granite followed by a passageway ending at the burial chamber. It has a gabled roof made of big limestone layers and fragments of the sarcophagus were found here when it was entered in the early 1800s.

Sahure established the Egyptian navy and sent a fleet to Punt and traded with Palestine. His pyramid at Abusir has colonnaded courts and reliefs of his naval fleet, but his military career consisted mostly of campaigns against the Libyans in the western desert. Reliefs on the walls show evidence for trading expeditions outside Egypt Ÿ ships are shown with both Egyptians and Asiatics on board. These ships are part of an expedition to the Lebanon, searching for cedar logs. This is corroborated by inscriptions found in the Lebanon testifying to an expedition there under Sahure. As part of the contacts with the Near-East, the reliefs from his funerary monuments also hold the oldest known representation of a Syrian bear.

A relief showing a war against Libya is believed by some to be historical and by others to be merely ritual. The Palermo-stone also mentions expeditions the the Sinai and to the exotic land of Punt, as well as to the diorite quarries North-West of Abu Simbel, thus far into Nubia.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

He was the third king of the 5th Dynasty.

Neferirkare was the second son of Khentkaus I to have ruled Egypt. As with his brother Sahure, it is not known whether Userkaf was his father. Neferirkare was married to a name-sake of his mother's, Khentkaus II. It is not unlikely that Khentkaus II too was related to Khentkaus I. At least two children are believed to have been born of this marriage: Neferefre and Niuserre. Other wives and children are not known.

The length of his reign is unfortunately lost on the Turin King-list and the Palermo-stone breaks of after having recorded a 5th counting, which, if the counting occurred every two years, would mean that Neferirkare at least ruled for 10 years. According to Manetho, his rule lasted for 20 years, a number which appears to be generally accepted.

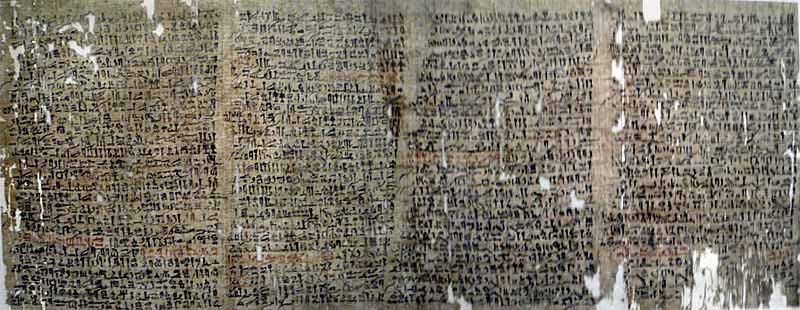

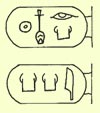

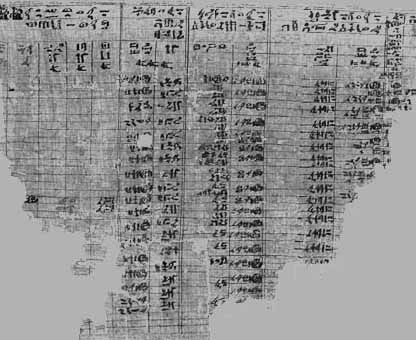

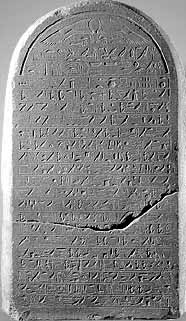

The Turin Canon, also known as the Turin Royal Canon is a unique papyrus, written in hieratic currently in the Egyptian Museum at Turin, to which it owes its modern name.

The Turin Canon is broken into over 160 often very small fragments, many of which have been lost. When it was discovered in the Theban necropolis by the Italian traveller Bernardino Drovetti in 1822, it seems to have been largely intact, but by the time it became part of the collection of the Egyptian Museum in Turin, its condition had severely deteriorated.

The importance of this papyrus was first recognised by the French Egyptologist Jean-Francois Champollion, who, later followed by Gustavus Seyffarth took up its reconstruction and restoration. Although they succeeded in placing most of the fragments in the correct order, the diligent intervention of these two men came too late and many lacunae still remain.

Written during the long reign of Ramesses II, the papyrus, now 1.7m long and 0.41m, comprises on the recto an unknown number of pages that hold a list of names of persons and institutions, along with what appears to be the tax-assessment of each.

It is, however, the verso of the papyrus that has attracted the most attention, as it contains a list of gods, demi-gods, spirits, mythical and human kings who ruled Egypt from the beginning of time presumably until the composition of this valuable document.

The beginning and ending of the list are now lost, which means that we are missing both the introduction of the list -if ever there was such an introduction- and the enumeration of the kings following the 17th Dynasty. We therefore do not know for certain when after the composition of the tax-list on the recto an unknown scribe used the verso to write down this list of kings. This may have occurred during the reign of Ramesses II, but a date as late as the Dynasty can not be excluded. The fact that the list was scribbled on the back of an older papyrus may indicate that it was of no great importance to the writer.

Neferirkare was the first king to have his birth-name made part of the official titulary, thus adding a second cartouche. He was the first king to have employed both a prenomen and nomen (two names and two cartouches),a custom that later kings would follow.

The hieratic papyrus found at his pyramid complex are probably his most notable contributions to Egyptology. They were originally discovered in 1893 by local farmers and consist of 300 papyrus fragments. They remained unpublished for some seventy-five years, even as the first archaeologists were excavating Abusir. Only later did a Czech mission, which explored the site in 1976, take full advantage of these documents.

The Neferirkara archive reveals a world of detailed and very professional administration. Elaborate tables provide monthly rosters of duty: for guarding the temple, for fetching the daily income (or 'offerings') and for performing ceremonies including those on the statues, with a special roster for the important Feast of Seker.

Similar tables list the temple equipment, item by item and grouped by materials, with details of damage noted at a monthly inspection. Other records of inspection relate to doors and rooms in the temple building. The presentation of monthly income is broken down by substance, source and daily amount. The commodities are primarily types of bread and beer, meat and fowl, corn and fruit. They also mention a mortuary temple of a little-known king, Raneferef, who's tomb was yet to be discovered but thanks to these papyrus, is now known and has yielded significant discoveries.

He also completed (or modified) the solar-temple built by Userkaf in Abusir. His own solar-temple, called Set-ib-Re, has yet to be located.

He was also the second king to erect his funerary monument at Abusir. The seals and papyri discovered in his mortuary temple give some insights into the functioning of this temple. The documents are dated to the end of the 6th Dynasty, which indicates that the cult for the deceased Neferirkare at least lasted until the end of the Old Kingdom.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

He was the fourth king of the 5th Dynasty.

Little to nothing is known about Shepseskare nor his relationship to the other kings of the 5th Dynasty. Shepseskare Isi, also spelt Shepseskare, (in Greek known as Sisiris), was Pharaoh of Egypt during the Fifth dynasty, and is thought to have reigned from around 2426 BC 2419 BC. Both the Turin King List and Manetho suggest that he ruled Egypt for seven years.

Several clay seals dated to his reign have been found at Abusir, and these are about the only witnesses of Shepseskare's reign. It is not known whether he built a pyramid or a solar-temple, although the unfinished pyramid located at Abusir between the pyramid of Sahure and the solar-temple of Userkaf, has, by some, been credited to him.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

He was the fifth king of the 5th Dynasty.

Neferefre was the first son of Neferirkare and Khentkaus II to come to the throne. The Turin King-list is too fragmentary to provide us with the length of Neferefre's reign.

He built a solar-temple named Hetep-Re, which has not yet been discovered, and, at Abusir, started with the building of his own pyramid complex which was left unfinished.

Because of the premature death of Neferefre, his successor hastily completed work on Neferefre's pyramid at Abusir, which acquired the form of a mastaba. Although it may share the same resemblance to a mastaba tomb, it is not situated north-south, and it is not rectangular in shape, but square on all sides.

Known as the "Unfinished Pyramid", it stands just seven meters high, but from the constructed portions, the walls slope at a 64º angle. Similarly to other sites of other Ancient Egyptian pyramids, the burial site of Neferefre contains more than one pyramid, and his lines up the three pyramids, similarly to the Great Pyramids.

Artifacts found at the sight show that the name of his pyramid is "Divine is Neferefre's Power." All the other buildings of Neferefre's mortuary complex were erected under the reign of his brother, Nyuserre Ini. While exploring ruins of the mortuary complex, a Czech archaeological expedition discovered papyri of temple accounts, statues of the king, decorated plates and many seal prints.

Pieces of mummy wrappings and bones were also found, which were discovered to be the remains of Neferefre. The anthropological analysis of his mummy reveals him to have died in his early twenties, between 20 and 23 Years, according to Verner. This evidence accords well for a king who died relatively soon into his reign.

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

He was the sixth king of the Fifth Dynasty.

Niuserre was the second son of Neferirkare and Khentkaus II to have ascended to the throne. He was married to a woman named Reputneb, of whom a statue was discovered in the valley-temple connected to his and Neferirkare's pyramid complex. It is not known whether he had any children (that out-lived him).

The Turin King-list is somewhat damaged at the point where Niuserre's name is mentioned, and only allows us to state that he ruled for more than 10 years. The 44 years credited to him by Manetho is considered unreliable. The representation of a Sed-festival found in his solar-temple may indicate that he ruled at least for 30 years.

An inscription found in the Sinai shown Niuserre triumphant over his enemies. It is debatable whether this inscription refers to an actual victory of Niuserre, or whether it was merely symbolic. It does, however, show that Niuserre was active in the Sinai.

He built a solar-temple, named Shesepu-ib-re, in Abu Gurab, a kilometre or more to the North of Abusir. Not only is this the biggest and most complete solar-temple, it is also the only one that was constructed completely of stone. The many finely carved reliefs that remain show the king during a Sed-festival and the world as created by the solar god, with representations of the seasons and the provinces of Egypt. With the reign of Niuserre, the solar-cult appears to have come to its summit.

The sanctuary consisted of an entrance hall that was leading to a court of 100x75 m / 330x250 ft. in size which was surrounded by a stone wall. In the middle of the courtyard stood a huge obelisk, a stone that looked like the modern-day Washington Monument. The obelisk was the cultic symbol for Re, the sun-god.

The pyramid-complex of Niuserre is located at Abusir, between the pyramids of Sahure and Neferirkare. Instead of building his own valley temple, he had his pyramid complex connected to the valley temple of Neferirkare. His two wives, Reputneb and Khentikus, were buried near him at Abusir.

His Cartouche

Astronomical Triangulations of Aries, Equinoxes,

Solstices and the Duat of Pharaonic Egypt

Reference: Monarchs of the Nile Aidan Dodson, 1995

Menkauhor was the seventh king of the 5th Dynasty.

His birth name was Kalu. According to the Turin King-list he ruled for some eight years. References fairly consistently give his reign as lasting from about 2421 or 2422 until 2414. He never achieved the level of fame of the other kings of the 5th dynasty. His reign is attested by an inscription in the Sinai and a seal from Abusir.

The relationship of Menkauhor with his predecessors or successors is not known. However, it is likely that he was either the brother or son of Niuserre, his predecessor. If he was Niuserre's son, it would probably have been by Niuserre's chief queen, Neput-Nebu. It is also likely that he was the father of Djedkare, who followed him to the throne. If not, he was almost certainly Djedkare's brother, with Niuserre being both king's father, or Djedkare's cousin, with Djedkare being the son of Neferefre, and Menkauhor being the son of Niuserre.

He is reputed as having sent his troops to Sinai in order to acquire materials for the construction of his tomb.

He was the last pharaoh to build a sun temple. His solar-temple, called Akhet-Re, and his pyramid are mentioned in texts from private tombs. This dynasty was famous for their solar temples, and Menkauhor's temple is probably located at either Abusir or Saqqara. It would have probably been the last such temple built, however, because his successors appear to have drifted away somewhat from the solar cult.

Menkauhor's pyramid has not been positively identified, but if the assumption that his pyramid is to be located at Dashur is correct, this would imply a departure from Abusir. However, some Egyptologists seem to strongly believe that his pyramid is the "Headless Pyramid", located in North Saqqara east of Teti's complex. There is mounting evidence to support this conclusion. B. G. Ockinga, for example argues that during the 18th Dynasty the Teti complex may have been associated with a cult belonging to a deified Menkauhor. Wherever it is located, his pyramid was called "Divine are the (cult) places of Menkauhor".

His reign is attested by an inscription in the Sinai at Magharah, indicating that he continued to quarry stone in that location as did his predecessors and successors. Given the lack of information on this king, we can also probably make some assumptions based on the activities of those predecessors and successors. For example, while he have no inscriptions as evidence, both Niuserre and Djedkare quarried stone northwest of Aswan, so it is likely that Menkauhor did as well.

It is also highly likely that he continued commercial and diplomatic relations with Byblos, as did both Niuserre and Djedkare, and in fact we do find a few objects in the area near Dorak bearing his name. It is also likely that he had some sort of dealings with Nubia, but whether he sent expeditions to Punt, as did Niuserre and Djedkare, is unknown.

Otherwise, Menkauhor is also attested to by a small alabaster statue that is now located in the Egyptian museum in Cairo and by a relief of Tjutju adoring King Menkauhor and other divinities. This relief, owned by the Louvre, has been on loan to the Cleveland Museum of Art.

There is also have a seal bearing his name that was found at Abusir.

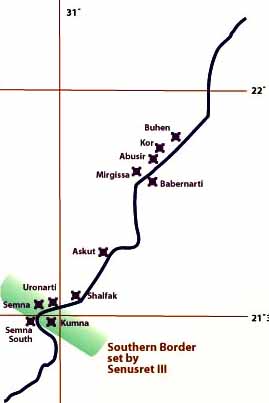

Djedkare was the eighth king of the 5th Dynasty.