Frederick Douglass

- The Liberator, September 22, 1848

- The long and intimate, though by no means friendly relation which unhappily subsisted between you and myself, leads me to hope that you will easily account for the great liberty which I now take in addressing you in this open and public manner. The same fact may possibly remove any disagreeable surprise which you may experience on again finding your name coupled with mine, in any other way than in an advertisement, accurately describing my person, and offering a large sum for my arrest. In thus dragging you again before the public, I am aware that I shall subject myself to no inconsiderable amount of censure. I shall probably be charged with an unwarrantable, if not a wanton and reckless disregard of the rights and proprieties of private life. There are those North as well as South who entertain a much higher respect for rights which are merely conventional, than they do for rights which are personal and essential. Not a few there are in our country, who, while they have no scruples against robbing the laborer of the hard earned results of hispatient industry, will be shocked by the extremely indelicate manner of bringing your name before the public. Believing this to be the case, and wishing to meet every reasonable or plausible objection to my conduct, I will frankly state the ground upon which I justify myself in this instance, as well as on former occasions when I have thought proper to mention your name in public. All will agree that a man guilty of theft, robbery, or murder, has forfeited the right to concealment and private life; that the community have a right to subject such persons to the most complete exposure. However much they may desire retirement, and aim to conceal themselves and their movements from the popular gaze, the public have a right to ferret them out, and bring their conduct before the proper tribunals of the country for investigation. Sir, you will undoubtedly make the proper application of these generally admitted principles, and will easily see the light in which you are regarded by me. I will not therefore manifest ill temper, by calling you hard names. I know you to be a man of some intelligence, and can readily determine the precise estimate which I entertain of your character. I may therefore indulge in language which may seem to others indirect and ambiguous, and yet be quite well understood by yourself.

- I have selected this day on which to address you, because it is the anniversary of my emancipation; and knowing of no better way, I am led to this as the best mode of celebrating that truly important event. Just ten years ago this beautiful September morning, yon bright sun beheld me a slave—a poor, degraded chattel—trembling at the sound of your voice, lamenting that I was a man, and wishing myself a brute. The hopes which I had treasured up for weeks of a safe and successful escape from your grasp, were powerfully confronted at this last hour by dark clouds of doubt and fear, making my person shake and my bosom to heave with the heavy contest between hope and fear. I have no words to describe to you the deep agony of soul which I experienced on that never to be forgotten morning—(for I left by daylight). I was making a leap in the dark. The probabilities, so far as I could by reason determine them, were stoutly against the undertaking. The preliminaries and precautions I had adopted previously, all worked badly. I was like one going to war without weapons—ten chances of defeat to one of victory. One in whom I had confided, and one who had promised me assistance, appalled by fear at the trial hour, deserted me, thus leaving the responsibility of success or failure solely with myself. You, sir, can never know my feelings. As I look back to them, I can scarcely realize that I have passed through a scene so trying. Trying however as they were, and gloomy as was the prospect, thanks be to the Most High, who is ever the God of the oppressed, at the moment which was to determine my whole earthly career. His grace was sufficient, my mind was made up. I embraced the golden opportunity, took the morning tide at the flood, and a free man, young, active and strong, is the result.

- I have often thought I should like to explain to you the grounds upon which I have justified myself in running away from you. I am almost ashamed to do so now, for by this time you may have discovered them yourself. I will, however, glance at them. When yet but a child about six years old, I imbibed the determination to run away. The very first mental effort that I now remember on my part, was an attempt to solve the mystery, Why am I a slave? and with this question my youthful mind was troubled for many days, pressing upon me more heavily at times than others. When I saw the slave-driver whip a slave woman, cut the blood out of her neck, and heard her piteous cries, I went away into the corner of the fence, wept and pondered over the mystery. I had, through some medium, I know not what, got some idea of God, the Creator of all mankind, the black and the white, and that he had made the blacks to serve the whites as slaves. How he could do this and be good, I could not tell. I was not satisfied with this theory, which made God responsible for slavery, for it pained me greatly, and I have wept over it long and often. At one time, your first wife, Mrs. Lucretia, heard me singing and saw me shedding tears, and asked of me the matter, but I was afraid to tell her. I was puzzled with this question, till one night, while sitting in the kitchen, I heard some of the old slaves talking of their parents having been stolen from Africa by white men, and were sold here as slaves. The whole mystery was solved at once. Very soon after this my aunt Jinny and uncle Noah ran away, and the great noise made about it by your father-in-law, made me for the first time acquainted with the fact, that there were free States as well as slave States. From that time, I resolved that I would some day run away. The morality of the act, I dispose as follows: I am myself; you are yourself; we are two distinct persons, equal persons. What you are, I am. You are a man, and so am I. God created both, and made us separate beings. I am not by nature bound to you, or you to me. Nature does not make your existence depend upon me, or mine to depend upon yours. I cannot walk upon your legs, or you upon mine. I cannot breathe for you, or you for me; I must breathe for myself, and you for yourself. We are distinct persons, and are each equally provided with faculties necessary to our individual existence. In leaving you, I took nothing but what belonged to me, and in no way lessened your means for obtaining an honest living. Your faculties remained yours, and mine became useful to their rightful owner. I therefore see no wrong in any part of the transaction. It is true, I went off secretly, but that was more your fault than mine. Had I let you into the secret, you would have defeated the enterprise entirely; but for this, I should have been really glad to have made you acquainted with my intentions to leave.

- You may perhaps want to know how I like my present condition. I am free to say, I greatly prefer it to that which I occupied in Maryland. I am, however, by no means prejudiced against the State as such. Its geography, climate, fertility and products, are such as to make it a very desirable abode for any man; and but for the existence of slavery there, it is not impossible that I might again take up my abode in that State. It is not that I love Maryland less, but freedom more. You will be surprised to learn that people at the North labor under the strange delusion that if the slaves were emancipated at the South, they would flock to the North. So far from this being the case, in that event, you would see many old and familiar faces back again to the South. The fact is, there are few here who would not return to the South in the event of emancipation. We want to live in the land of our birth, and to lay our bones by the side of our fathers'; and nothing short of an intense love of personal freedom keeps us from the South. For the sake of this, most of us would live on a crust of bread and a cup of cold water.

- Since I left you, I have had a rich experience. I have occupied stations which I never dreamed of when a slave. Three out of the ten years since I left you, I spent as a common laborer on the wharves of New Bedford, Massachusetts. It was there I earned my first free dollar. It was mine. I could spend it as I pleased. I could buy hams or herring with it, without asking any odds of any body. That was a precious dollar to me. You remember when I used to make seven or eight, or even nine dollars a week in Baltimore, you would take every cent of it from me every Saturday night, saying that I belonged to you, and my earnings also. I never liked this conduct on your part—to say the best, I thought it a little mean. I would not have served you so. But let that pass. I was a little awkward about counting money in New England fashion when I first landed in New Bedford. I like to have betrayed myself several times. I caught myself saying phip, for fourpence; and at one time a man actually charged me with being a runaway, whereupon I was silly enough to become one by running away from him, for I was greatly afraid he might adopt measures to get me again into slavery, a condition I then dreaded more than death.

- I soon, however, learned to count money, as well as to make it, and got on swimmingly. I married soon after leaving you: in fact, I was engaged to be married before I left you; and instead of finding my companion a burden, she was truly a helpmeet. She went to live at service, and I to work on the wharf, and though we toiled hard the first winter, we never lived more happily. After remaining in New Bedford for three years, I met with Wm. Lloyd Garrison, a person of whom you have possibly heard, as he is pretty generally known among slaveholders. He put it into my head that I might make myself serviceable to the cause of the slave by devoting a portion of my time to telling my own sorrows, and those of other slaves which had come under my observation. This was the commencement of a higher state of existence than any to which I had ever aspired. I was thrown into society the most pure, enlightened and benevolent that the country affords. Among these I have never forgotten you, but have invariably made you the topic of conversation—thus giving you all the notoriety I could do. I need not tell you that the opinion formed of you in these circles, is far from being favorable. They have little respect for your honesty, and less for your religion.

- But I was going on to relate to you something of my interesting experience. I had not long enjoyed the excellent society to which I have referred, before the light of its excellence exerted a beneficial influence on my mind and heart. Much of my early dislike of white persons was removed, and their manners, habits and customs, so entirely unlike what I had been used to in the kitchen-quarters on the plantations of the South, fairly charmed me, and gave me a strong disrelish for the coarse and degrading customs of my former condition. I therefore made an effort so to improve my mind and deportment, as to be somewhat fitted to the station to which I seemed almost providentially called. The transition from degradation to respectability was indeed great, and to get from one to the other without carrying some marks of one's former condition, is truly a difficult matter. I would not have you think that I am now entirely clear of all plantation peculiarities, but my friends here, while they entertain the strongest dislike to them, regard me with that charity to which my past life somewhat entitles me, so that my condition in this respect is exceedingly pleasant. So far as my domestic affairs are concerned, I can boast of as comfortable a dwelling as your own. I have an industrious and neat companion, and four dear children—the oldest a girl of nine years, and three fine boys, the oldest eight, the next six, and the youngest four years old. The three oldest are now going regularly to school—two can read and write, and the other can spell with tolerable correctness words of two syllables: Dear fellows! they are all in comfortable beds, and are sound asleep, perfectly secure under my own roof. There are no slaveholders here to rend my heart by snatching them from my arms, or blast a mother's dearest hopes by tearing them from her bosom. These dear children are ours—not to work up into rice, sugar and tobacco, but to watch over, regard, and protect, and to rear them up in the nurture and admonition of the gospel—to train them up in the paths of wisdom and virtue, and, as far as we can to make them useful to the world and to themselves. Oh! sir, a slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children. It is then that my feelings rise above my control. I meant to have said more with respect to my own prosperity and happiness, but thoughts and feelings which this recital has quickened unfits me to proceed further in that direction. The grim horrors of slavery rise in all their ghastly terror before me, the wails of millions pierce my heart, and chill my blood. I remember the chain, the gag, the bloody whip, the deathlike gloom overshadowing the broken spirit of the fettered bondman, the appalling liability of his being torn away from wife and children, and sold like a beast in the market. Say not that this is a picture of fancy. You well know that I wear stripes on my back inflicted by your direction; and that you, while we were brothers in the same church, caused this right hand, with which I am now penning this letter, to be closely tied to my left, and my person dragged at the pistol's mouth, fifteen miles, from the Bay side to Easton to be sold like a beast in the market, for the alleged crime of intending to escape from your possession. All this and more you remember, and know to be perfectly true, not only of yourself, but of nearly all of the slaveholders around you.

- At this moment, you are probably the guilty holder of at least three of my own dear sisters, and my only brother in bondage. These you regard as your property. They are recorded on your ledger, or perhaps have been sold to human flesh mongers, with a view to filling your own ever-hungry purse. Sir, I desire to know how and where these dear sisters are. Have you sold them? or are they still in your possession? What has become of them? are they living or dead? And my dear old grandmother, whom you turned out like an old horse, to die in the woods—is she still alive? Write and let me know all about them. If my grandmother be still alive, she is of no service to you, for by this time she must be nearly eighty years old—too old to be cared for by one to whom she has ceased to be of service, send her to me at Rochester, or bring her to Philadelphia, and it shall be the crowning happiness of my life to take care of her in her old age. Oh! she was to me a mother, and a father, so far as hard toil for my comfort could make her such. Send me my grandmother! that I may watch over and take care of her in her old age. And my sisters, let me know all about them. I would write to them, and learn all I want to know of them, without disturbing you in any way, but that, through your unrighteous conduct, they have been entirely deprived of the power to read and write. You have kept them in utter ignorance, and have therefore robbed them of the sweet enjoyments of writing or receiving letters from absent friends and relatives. Your wickedness and cruelty committed in this respect on your fellow-creatures, are greater than all the stripes you have laid upon my back, or theirs. It is an outrage upon the soul—a war upon the immortal spirit, and one for which you must give account at the bar of our common Father and Creator.

- The responsibility which you have assumed in this regard is truly awful—and how you could stagger under it these many years is marvellous. Your mind must have become darkened, your heart hardened, your conscience seared and petrified, or you would have long since thrown off the accursed load and sought relief at the hands of a sin-forgiving God. How, let me ask, would you look upon me, were I some dark night in company with a band of hardened villains, to enter the precincts of your elegant dwelling and seize the person of your own lovely daughter Amanda, and carry her off from your family, friends and all the loved ones of her youth—make her my slave—compel her to work, and I take her wages—place her name on my ledger as property—disregard her personal rights—fetter the powers of her immortal soul by denying her the right and privilege of learning to read and write—feed her coarsely—clothe her scantily, and whip her on the naked back occasionally; more and still more horrible, leave her unprotected—a degraded victim to the brutal lust of fiendish overseers, who would pollute, blight, and blast her fair soul—rob her of all dignity—destroy her virtue, and annihilate all in her person the graces that adorn the character of virtuous womanhood? I ask how would you regard me, if such were my conduct? Oh! the vocabulary of the damned would not afford a word sufficiently infernal, to express your idea of my God-provoking wickedness. Yet sir, your treatment of my beloved sisters is in all essential points, precisely like the case I have now supposed. Damning as would be such a deed on my part, it would be no more so than that which you have committed against me and my sisters.

- I will now bring this letter to a close, you shall hear from me again unless you let me hear from you. I intend to make use of you as a weapon with which to assail the system of slavery—as a means of concentrating public attention on the system, and deepening their horror of trafficking in the souls and bodies of men. I shall make use of you as a means of exposing the character of the American church and clergy—and as a means of bringing this guilty nation with yourself to repentance. In doing this I entertain no malice towards you personally. There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege, to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other. I am your fellow man, but not your slave,Frederick DouglassThe Liberator, September 22, 1848

To Thomas Auld

September 3d, 1848

Sir:

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

Chapters VII–VIII

Summary: Chapter VII

Douglass lives in Hugh Auld’s household for about seven years. During this time, he is able to learn how to read and write, though Mrs. Auld is hardened and no longer tutors him. Slavery hurts Mrs. Auld as much as it hurts Douglass himself. The mentality of slavery strips her of her inherent piety and sympathy for others, making her hardened and cruel.

However, Douglass has already learned the alphabet and is determined to learn how to read. He gives bread to poor local boys in exchange for reading lessons. Douglass writes that he is now tempted to thank these boys by name, but he knows that they would suffer for it, as teaching blacks still constitutes an offense. Douglass recalls the boys sympathetically agreeing that he no more deserved to be a slave than they did themselves.

At around the age of twelve, Douglass encounters a book called The Columbian Orator, which contains a philosophical dialogue between a master and a slave. In the dialogue, the master lays out the argument for slavery, and the slave refutes each point, eventually convincing the master to release him. The book also contains a reprint of a speech arguing for the emancipation of Irish Catholics and for human rights generally. The book helps Douglass to fully articulate the case against slavery, but it also makes him hate his masters more and more. This dilemma is difficult position for Douglass and often fills him with regret. As Hugh Auld predicted, Douglass’s discontent is painfully acute now that he understands the injustice of his situation but still has no means by which to escape it. Douglass enters a period of nearly suicidal despair.

During this period, Douglass eagerly listens to anyone discussing slavery. He often hears the word “abolitionist.” In a city newspaper account of a Northern abolitionist petition, Douglass finally discovers that the word means “antislavery.”

One day around this time, Douglass kindly helps two Irish sailors at the wharf without being asked. When they realize that Douglass is doomed to be a slave for life, the sailors encourage him to run away to the North. Douglass does not respond to them, for fear they might be trying to trick him. White men are known to encourage slaves to escape and then recapture them for the reward money. But the idea of escape nonetheless sticks in Douglass’s head.

Meanwhile, Douglass sets out to learn how to write. After watching ships’ carpenters write single letters on lumber, Douglass learns to form several letters. He practices his letters on fences, walls, and the ground around the city. He approaches local boys and starts contests over who can write the best. Douglass writes what he can and learns from what the boys write. Soon, he can copy from the dictionary. When the Aulds leave Douglass alone in the house, he writes in Thomas Auld’s old discarded copybooks. In this painstaking manner, Douglass eventually learns to write.

Summary: Chapter VIII

During Douglass’s first several years in Baltimore, his old master, Captain Anthony, dies. When Douglass is between ten and eleven years old, he is returned to the plantation to be appraised among the other slaves and the livestock, which are to be divided between Captain Anthony’s surviving children, Mrs. Lucretia Auld and Andrew Anthony. Douglass is apprehensive about leaving Baltimore because he knows his life in the city is preferable to the plantation.

The valuation of the slaves is humiliating, as they are inspected alongside the livestock. All the slaves are anxious, knowing they are to be divided regardless of marriages, family, and friendships. Master Andrew is known for his cruelty and drunkenness, so everyone hopes to avoid becoming his property. Since Douglass’s return to the plantation, he has seen Master Andrew kick Douglass’s younger brother in the head until he bled. Master Andrew has threatened to do the same to Douglass.

Luckily, Douglass is assigned to Mrs. Lucretia Auld, who sends him back to Baltimore. Soon after Douglass returns there, Mrs. Lucretia and Master Andrew both die, leaving all the Anthony family property in the hands of strangers. Neither Lucretia nor Andrew frees any of the slaves before dying—not even Douglass’s grandmother, who nurtured Master Andrew from infancy to death. Because Douglass’s grandmother is deemed too old to work in the fields, her new owners abandon her in a small hut in the woods. Douglass bemoans this cruel fate. He imagines that if his grandmother were still alive today, she would be cold and lonely, mourning the loss of her children.

About two years after the death of Lucretia Auld, her husband, Thomas Auld, remarries. Soon after the marriage, Thomas has a falling out with his brother, Hugh, and punishes Hugh by reclaiming Douglass. Douglass is not sorry to leave Hugh and Sophia Auld, as Hugh has become a drunk and Sophia has become cruel. But Douglass is sorry to leave the local boys, who have become his friends and teachers.

While sailing from Baltimore back to the Eastern Shore of -Maryland, Douglass pays particular attention to the route of the ships heading north to Philadelphia. He resolves to escape at the -earliest opportunity.

Analysis: Chapters VII–VIII

In Chapters VII and VIII, Douglass relates events slightly out of chronological order, again disrupting the Narrative’s appearance of -autobiography. His brief return to the plantation, recounted in Chapter VIII, actually takes place before he reads The Colombian Orator, recounted in Chapter VII. Douglass records the events out of order because he favors thematic consistency over strict chronology. As Chapter VI deals with Hugh Auld forbidding Sophia to teach Douglass to read, Chapter VII addresses Douglass’s self-education and the fulfillment of Hugh Auld’s predictions of unhappiness.

Chapter VII elaborates the idea that with education comes enlightenment—specifically, enlightenment about the oppressive and wrong nature of slavery. Douglass’s reading lessons and acts of reading are, therefore, contiguous with his growing understanding of the social injustice of slavery. Douglass gets his first reading lessons from neighborhood boys and also engages in discussions about the institution of slavery with them. These boys not only provide the means of Douglass’s education, but also support his growing political convictions. In this way, Douglass depicts each step in his educational process as a simultaneous step in philosophical and political enlightenment.

Douglass’s encounter with The Columbian Orator represents the main event of Douglass’s educational and philosophical growth. This book features both a Socratic‑style dialogue between an archetypal “master” and “slave” and a speech in favor of Irish Catholic emancipation. Douglass has a sense of the inhumanity of slavery before he reads The Columbian Orator, but the book gives him a clear articulation of the political and philosophical argument against slavery and in favor of human rights. It allows Douglass to formulate his personal thoughts and convictions about slavery. However, the book also causes Douglass to detest his masters. Painfully, he understands the injustice of his position, but has no immediate means of escape. In this regard, Douglass fulfills Hugh Auld’s prediction that educated slaves become unhappy. Douglass’s unhappiness shows that education does not directly bring freedom. His new consciousness of injustice has drawbacks, and intellectual freedom is not the same as physical freedom.

Chapters VII and VIII further develop the Narrative’s motif of the greater freedom of the city compared to the countryside. Chapter VII takes place in Baltimore and features Douglass’s free movements and self-education. Douglass hardly discusses the Aulds or their cruel treatment in Chapter VII. Instead, he focuses on his intellectually fruitful interactions with people around the city, such as neighborhood boys and dock workers. Chapter VIII, however, deals with Douglass’s time in the countryside. First, Douglass discusses his brief trip back to the Eastern Shore around age ten and then his return to Thomas Auld’s plantation three years later. These disparate historical events are out of chronological order with the events of Chapter VII. They are united in one chapter because of their common rural setting. Douglass portrays the oppressive atmosphere of the rural plantation, where slaves are closely watched, harshly punished, and treated as property.

In Chapter VIII, Douglass elaborates on the idea of slave owners treating slaves as property through his depiction of the valuation of Captain Anthony’s slaves. Douglass ironically describes how Captain Anthony’s slaves are lined up alongside the livestock to be valued in the same manner. Douglass’s irony points to the absurdity of treating humans as animals. Douglass further develops this idea by showing how slaves are frequently passed from owner to owner as property. In Chapter VIII alone, Douglass is under the ownership of Captain Anthony, then Lucretia and Thomas Auld, then Hugh Auld, and then Thomas Auld once again. Douglass’s extended description of the Anthony family’s treatment of his grandmother particularly develops this motif of ownership. Though Douglass’s grandmother lovingly tends the Anthony children for her entire life, they do not grant her freedom even in her old age. Because slave owners value slaves only according to the amount labor they can do, Douglass’s grandmother’s new owners abandon the elderly woman.

Several times in his Narrative, Douglass breaks the conventions of his past‑tense autobiography to recreate a scene imaginatively. In his discussion of the treatment of his grandmother, Douglass imagines that she is still alive as he is writing. He creates an image of her stumbling around her small hut, waiting for death. This imagined scene works in the same ways as sentimental fiction. Douglass evokes the conventional scene of the home hearth surrounded by happy children to contrast it with the desolation of his grandmother’s life. Douglass’s grandmother becomes an object of sympathy—a sympathy meant to translate into outrage and political conviction.

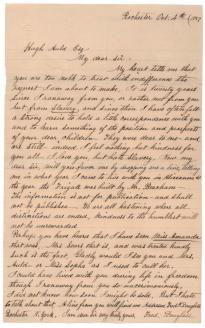

“I love you but hate slavery”: Frederick Douglass to his former owner, Hugh Auld, 1857

by Frederick Douglass

Following his escape from slavery in Maryland to freedom in New York City in 1838, Frederick Douglass became a leader of the abolition movement and its best-known orator. His book Autobiography of an American Slave became a best seller and exposed the horrors of slavery. In this letter dated October 4, 1857, Douglass wrote to his former master expressing the desire to learn more about his own childhood and the children with whom he grew up. This letter also reflects Douglass’s capacity for forgiveness and is part of his lifelong quest, shared by all slaves, to establish his own history and know when his birthday was and who his parents and siblings were.

In an extraordinary display of forgiveness, Douglass writes to Hugh Auld, his former master: “I love you, but hate slavery.”

A full transcript is available.

TRANSCRIPT

Rochester Oct. 4th (1857

Hugh Auld Esq

My dear Sir.

My heart tells me that you are too noble to treat with indifference the request I am about to make, It is twenty years since I ran away from you, or rather not from you but from Slavery, and since then I have often felt a strong desire to hold a little correspondence with you and to learn something of the position and prospects of your dear children. They were dear to me – and are still – indeed I feel nothing but kindness for you all – I love you, but hate Slavery, Now my dear Sir, will you favor me by dropping me a line, telling me in what year I came to live with you in Aliceanna St. the year the Frigate was built by Mr. Beacham. The information is not for publication – and shall not be published. We are all hastening where all distinctions are ended, kindness to the humblest will not be unrewarded

My dear Sir.

My heart tells me that you are too noble to treat with indifference the request I am about to make, It is twenty years since I ran away from you, or rather not from you but from Slavery, and since then I have often felt a strong desire to hold a little correspondence with you and to learn something of the position and prospects of your dear children. They were dear to me – and are still – indeed I feel nothing but kindness for you all – I love you, but hate Slavery, Now my dear Sir, will you favor me by dropping me a line, telling me in what year I came to live with you in Aliceanna St. the year the Frigate was built by Mr. Beacham. The information is not for publication – and shall not be published. We are all hastening where all distinctions are ended, kindness to the humblest will not be unrewarded

Perhaps you have heard that I have seen Miss Amanda that was, Mrs. Sears that is, and was treated kindly such is the fact, Gladly would I see you and Mrs. Auld – or Miss Sopha as I used to call her. I could have lived with you during life in freedom though I ran away from you so unceremoniously, I did not know how soon I might be sold. But I hate to talk about that. A line from you will find me Addressed FredK Douglass Rochester N. York. I am dear sir very truly yours. Fred: Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, c. February 1818[3] – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, orator, writer and statesman. After escaping from slavery, he became a leader of the abolitionist movement, gaining note for his dazzling oratory[4] and incisive antislavery writing. He stood as a living counter-example to slaveholders' arguments that slaves did not have the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.[5][6] Many Northerners also found it hard to believe that such a great orator had been a slave.[7]

Douglass wrote several autobiographies, eloquently describing his experiences in slavery in his 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, which became influential in its support for abolition. He wrote two more autobiographies, with his last, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, published in 1881 and covering events through and after the Civil War. After the Civil War, Douglass remained active in the United States' struggle to reach its potential as a "land of the free". Douglass actively supported women's suffrage. Without his approval, he became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States as the running mate of Victoria Woodhull on the impracticable and small Equal Rights Party ticket.[8]Douglass held multiple public offices.

Douglass was a firm believer in the equality of all people, whether black, female, Native American, or recent immigrant, famously quoted as saying, "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."[9]

Life as a slave

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, who later became known as Frederick Douglass, was born a slave in Talbot County, Maryland, between Hillsboro[10] and Cordova, probably in his grandmother's shack east of Tappers Corner (38.8845°N 75.958°W) and west of Tuckahoe Creek.[11] The exact date of Douglass' birth is unknown. He chose to celebrate it on February 14.[3] The exact year is also unknown (on the first page of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, he stated: "I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it.")[10][12] He spoke of his earliest times with his mother:

- "The opinion was ... whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion I know nothing.... My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant.... It [was] common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age.

"I do not recollect ever seeing my mother by the light of day. ... She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone."[13] - After this separation, he lived with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. His mother died when Douglass was about ten. At age seven, Douglass was separated from his grandmother and moved to the Wye House plantation, where Aaron Anthony worked as overseer.[14] When Anthony died, Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld. She sent Douglass to serve Thomas' brother Hugh Auld in Baltimore.

- When Douglass was about twelve years old, Hugh Auld's wife Sophia started teaching him the alphabet despite the fact that it was against the law to teach slaves to read. Douglass described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman, who treated Douglass the way one human being ought to treat another. When Hugh Auld discovered her activity, he strongly disapproved, saying that if a slave learned to read, he would become dissatisfied with his condition and desire freedom. Douglass later referred to this statement as the "first decidedly antislavery lecture" he had ever heard.[15] As told in his autobiography, Douglass succeeded in learning to read from white children in the neighborhood and by observing the writings of men with whom he worked. Mrs. Auld one day saw Douglass reading a newspaper; she ran over to him and snatched it from him, with a face that said education and slavery were incompatible with each other.

- He continued, secretly, to teach himself how to read and write. Douglass is noted as saying that "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom."[16] As Douglass began to read newspapers, political materials, and books of every description, he was exposed to a new realm of thought that led him to question and condemn the institution of slavery. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator, which he discovered at about age twelve, with clarifying and defining his views on freedom and human rights.

- When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he taught other slaves on the plantation to read the New Testament at a weekly Sunday school. As word spread, the interest among slaves in learning to read was so great that in any week, more than 40 slaves would attend lessons. For about six months, their study went relatively unnoticed. While Freeland was complacent about their activities, other plantation owners became incensed that their slaves were being educated. One Sunday they burst in on the gathering, armed with clubs and stones, to disperse the congregation permanently.

- In 1833, Thomas Auld took Douglass back from Hugh after a dispute ("[a]s a means of punishing Hugh," Douglass wrote). Dissatisfied with Douglass, Thomas Auld sent him to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker." He whipped Douglass regularly. The sixteen-year-old Douglass was nearly broken psychologically by his ordeal under Covey, but he finally rebelled against the beatings and fought back. After losing a physical confrontation with Douglass, Covey never tried to beat him again.[17]

- In 1921, members of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity (the first African-American intercollegiate fraternity) designated Frederick Douglass as an honorary member. And so Douglass is the only man to receive an honorary membership posthumously.[57]

- The Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge, sometimes referred to as the South Capitol Street Bridge, just south of the US Capitol in Washington DC, was built in 1950 and named in his honor.

- In 1962, his home in Anacostia (Washington, DC) became part of the National Park System,[58] and in 1988 was designated the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

- In 1965, the U.S. Postal Service honored Douglass with a stamp in theProminent Americans series.

- In 1999, Yale University established the Frederick Douglass Book Prize for works in the history of slavery and abolition, in his honor. The annual $25,000 prize is administered by the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History and the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Frederick Douglass to his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[59]

- In 2003, Douglass Place, the rental housing units that Douglass built in Baltimore in 1892 for blacks, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Douglass is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on February 20.

- In 2007, the former Troup–Howell bridge which carried Interstate 490 over the Genesee River was redesigned and renamed theFrederick Douglass – Susan B. Anthony Memorial Bridge.

- In 2010, a statue (by Gabriel Koren) and memorial (designed by Algernon Miller) of Douglass[60] were unveiled at Frederick Douglass Circle at the northwest corner of Central Park in New York City.[61]

- On June 12, 2011, Talbot County, Maryland, honored Douglass by installing a seven-foot bronze statue of Douglass on the lawn of the county courthouse in Easton, Maryland.[62]

- Many public schools have been named in his honor.

- A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845)

- "The Heroic Slave". Autographs for Freedom. Ed. Julia Griffiths, Boston: Jewett and Company, 1853. pp. 174–239.

- My Bondage and My Freedom (1855)

- Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised 1892)

- Douglass founded and edited the abolitionist newspaper The North Star from 1847 to 1851. He merged The North Star with another paper to create the Frederick Douglass' Paper.

- In the Words of Frederick Douglass: Quotations from Liberty's Champion. Edited by John R. McKivigan and Heather L. Kaufman. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-8014-4790-7

- "The Church and Prejudice"

- Self-Made Men

- "Speech at National Hall, Philadelphia July 6, 1863 for the Promotion of Colored Enlistments"[63]

- "What to a slave is the 4th of July?"[64]

- The 1989 film Glory featured Frederick Douglass as a friend of Francis George Shaw. He was played by Raymond St. Jacques.

- Douglass is the protagonist of the novel Riversmeet (Richard Bradbury, Muswell Press, 2007), a fictionalized account of his 1845 speaking tour of the British Isles.[65]

- The 2004 mockumentary film, an alternative history called C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America, featured the figure of Douglass.

- The 2008 documentary film called Frederick Douglass and the White Negro tells the story of Frederick Douglass in Ireland and the relationship between African Americans and Irish Americans during the American Civil War.

- Frederick Douglass is a major character in the novel How Few Remain by Harry Turtledove, an alternate history in which the Confederacy won the Civil War and Douglass must continue his anti-slavery campaign into the 1880s.

- Frederick Douglass appears in Flashman and the Angel of the Lord, by George MacDonald Fraser.

- Terry Bisson's 1988 novel Fire on the Mountain is an alternate history in which John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry succeeded and instead of the Civil War the Black slaves emancipated themselves in a massive slave revolt. In this history Frederick Douglass (along with Harriet Tubman) is the revered Founder of a Black state created in the Deep South.

- Frederick Douglass appears as a Great Humanitarian in the 2008 strategy video game Civilization Revolution.[66]

- Douglass, his wife, and his mistress, Ottilie Assing, are the main characters in Jewell Parker Rhodes' Douglass' Women, a novel (New York: Atria Books, 2002).

- African-American literature

- Frederick Douglass and the White Negro

- List of African-American abolitionists

- Slave narrative

- The Columbian Orator

- U.S. Constitution, defender of the Constitution

- ^ "Frederick Douglass". Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ "How Slavery Affected African American Families, Freedom's Story, TeacherServe®, National Humanities Center". Nationalhumanitiescenter.org. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ a b "Frederick Douglass Biography". Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Willard B. Gatewood Jr. (January 1981). "Frederick Doulass and the Building of a "Wall of Anti-Slavery Fire," 1845-1846. An Essay Review". The Florida Historical Quarterly 59 (3): 340–344. JSTOR 30147499.

- ^ Social Studies School Service (2005).Big Ideas in U.S. History. Social Studies. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-56004-206-8. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ Bill E. Lawson; Frank M. Kirkland (January 10, 1999). Frederick Douglass: a critical reader. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-0-631-20578-4. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ "Radical Reform and Antislavery". Retrieved March 17, 2011. "When many Northerners refused to believe that this eloquent orator could have been a slave, he responded by writing an autobiography that identified his previous owners by name."

- ^ a b Trotman, C. James (2011).Frederick Douglass: A Biography. Penguin Books. pp. 118-119.ISBN 978-0-313-35036-8.

- ^ Frederick Douglass (1855). The Anti-Slavery Movement, A Lecture by Frederick Douglass before the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. Retrieved October 6, 2010.From page 33: 'My point here is, first, the Constitution is, according to its reading, an anti-slavery document; and, secondly, to dissolve the Union, as a means to abolish slavery, is about as wise as it would be to burn up this city, in order to get the thieves out of it. But again, we hear the motto, "no union with slave-holders;" and I answer it, as the noble champion of liberty, N. P. Rogers, answered it with a more sensible motto, namely—"No union with slave-holding." I would unite with anybody to do right; and with nobody to do wrong.'

- ^ a b Frederick Douglass (1845).Narrative of the Life of an American Slave. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

Frederick Douglass began his own story thus: "I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland." (Tuckahoe is not a town; it refers to the area west of the creek in Talbot County.) In successive autobiographies, Douglass gave more precise estimates of when he was born, his final estimate being 1817. He adopted February 14 as his birthday because his mother Harriet Bailey used to call him her "little valentine". - ^ Amanda Barker (1996). "The Search for Frederick Douglass' Birthplace". Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ Slaves were punished for learning to read or write and so could not keep records. Based on the records of Douglass' former owner Aaron Anthony, historian Dickson Preston determined that Douglass was born in February 1818. McFeely, 1991, p. 8.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1851). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave. Written by himself.(6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. p. 10.

- ^ ""Frederick Douglass: Talbot County's Native Son", The Historical Society of Talbot County, Maryland".

- ^ Douglass, Frederick. The life and times of Frederick Douglass: his early life as a slave, his escape from bondage, and his complete history, p. 50. Dover Value Editions, Courier Dover Publications, 2003. ISBN 0-486-43170-3

- ^ Jacobs, H. and Appiah, K. (2004).Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave & Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.Mass Market Paperback, pp. xiii, 4.

- ^ Bowers, Jerome. Frederick Douglass. Teachinghistory.org. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Julius Eric Thompson; James L. Conyers (2010). The Frederick Douglass encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-313-31988-4. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ "Anna Murray Douglass".BlackPast.org. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Waldo E. Martin (March 1, 1986). The mind of Frederick Douglass. UNC Press Books. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8078-4148-8. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "Discovering Anna Murray Douglass". South Coast Today. February 17, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1882). Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. p. 170. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1882). Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. pp. 287–288. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1882). Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. p. 205. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ Chaffin, Tom (February 25, 2011)."Frederick Douglass's Irish Liberty".The New York Times. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Marianne Ruuth (1996).Frederick Douglass p.117-118. Holloway House Publishing, 1996

- ^ Frances E. Ruffin (2008). Frederick Douglass: Rising Up from Slavery. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4027-4118-0. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ^ Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution, New York: HarperCollins, 2006 Pbk, pp. 415–421

- ^ a b c Paul Finkelman (2006).Encyclopedia of African American history, 1619–1895: from the colonial period to the age of Frederick Douglass. Oxford University Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-19-516777-1. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "I am your fellow man, but not your slave,". Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Seneca Falls Convention". Virginia Memory. August 18, 1920. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Stanton, 1997, p. 85.

- ^ USConstitution.net. Text of the "Declaration of Sentiments", and the Resolutions. Retrieved on April 24, 2009.

- ^ a b c McMillen, 2008, pp. 93–94.

- ^ National Park Service. Women's Rights. Report of the Woman's Rights Convention, July 19–20, 1848. Retrieved on April 24, 2009.

- ^ University of Rochester Frederick Douglass Project. [1]. Retrieved on November 26, 2010.

- ^ Slaves in Union-held areas were not covered by this war-measures act.

- ^ "The Fight For Emancipation". Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ^ Stauffer (2008), Giants, p. 280

- ^ Frederick Douglass; Robert G. O'Meally (November 30, 2003).Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave. Spark Educational Publishing. p. xi. ISBN 978-1-59308-041-9. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ^ "Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln by Frederick Douglass". Teachingamericanhistory.org. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ Robin Van Auken, Louis E Hunsinger (2003). Williamsport: Boomtown on the Susquehanna. Arcadia Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 0-7385-2438-7.

- ^ This is an early version of the four boxes of liberty concept later used by conservatives opposed to gun control

- ^ George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon",Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, pp.12–13, accessed March 10, 2008

- ^ Olasky, Marvin. "History turned right side up". WORLD magazine. February 13, 2010. p. 22.

- ^ Julius Eric Thompson; James L. Conyers (2010). The Frederick Douglass encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-313-31988-4. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Frederick Douglass biography at winningthevote.org. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

- ^ Julius Eric Thompson; James L. Conyers (2010). The Frederick Douglass encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-313-31988-4. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel "The Warmth of Other Suns" (2010) p. 40

- ^ Richard Reid, "The Gloria Rackley-Blackwell story" The Times and Democrat, (February 22, 2011). Retrieved June 3, 2011

- ^ "Past Convention Highlights." Republican Convention 2000.CNN/AllPolitics.com. Retrieved July 1, 2008.

- ^ National Convention, Republican Party (U.S. : 1854- ) (1903). Official Proceedings of the Republican National Convention Held at Chicago, June 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 and 25, 1888.

- ^ "CNN: Think you know your Democratic convention trivia?". August 26, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2008-04-15.

- ^ "Maryland Historical Trust".Douglass Place, Baltimore City. Maryland Historical Trust. November 21, 2008.

- ^ "Prominent Alpha Men". Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ^ "Frederick Douglass Bill is Approved by President: Bill making F Douglass home, Washington, DC, part of natl pk system signed". The New York Times. September 6, 1962.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ Clines, Francis X. (November 3, 2006). "Summoning Frederick Douglass". The New York Times.

- ^ Dominus, Susan (May 21, 2010). [A Slow Tribute That Might Try the Subject’s Patience "A Slow Tribute That Might Try the Subject’s Patience"]. The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Holt, Dustin (June 12, 2011)."Douglass statue arrives in Easton".The Star Democrat. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ archive.org

- ^ lib.rochester.edu

- ^ "Frederick Douglass and 'Riversmeet': connecting 19th century struggles", Socialist Worker online, December 1, 2007

- ^ Civilization Revolution: Great People "CivFanatics" Retrieved on September 3, 2009

- Scholarship

- Gates, Jr., Henry Louis, ed. Frederick Douglass, Autobiography (Library of America, 1994) ISBN 978-0-940450-79-0

- Foner, Philip Sheldon. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

- Houston A. Baker, Jr., Introduction, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Penguin, 1986 edition.

- Huggins, Nathan Irvin, and Oscar Handlin. Slave and Citizen: The Life of Frederick Douglass. Library of American Biography. Boston: Little, Brown, 1980; Longman (1997). ISBN 0-673-39342-9

- Lampe, Gregory P. Frederick Douglass: Freedom's Voice. Rhetoric and Public Affairs Series. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1998. ISBN-X (alk. paper) ISBN (pbk. alk. paper) (on his oratory)

- Levine, Robert S. Martin Delany, Frederick Douglass, and the Politics of Representative Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN (alk. paper). ISBN (pbk.: alk. paper) (cultural history)

- McFeely, William S. Frederick Douglass. New York: Norton, 1991. ISBN 0-393-31376-X

- McMillen, Sally Gregory. Seneca Falls and the origins of the women's rights movement. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-19-518265-0

- Oakes, James. The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics.New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. 2007. ISBN 0-393-06194-9

- Quarles, Benjamin. Frederick Douglass. Washington: Associated Publishers, 1948.

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; edited by Theodore Stanton and Harriot Stanton Blatch. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, As Revealed in Her Letters, Diary and Reminiscences, Harper & Brothers, 1922.

- Webber, Thomas, Deep Like Rivers: Education in the Slave Quarter Community 1831–1865. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. (1978).

- Woodson, C.G., The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861: A History of the Education of the Colored People of the United States from the Beginning of Slavery to the Civil War. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, (1915); Indy Publ. (2005) ISBN 1-4219-2670-9

- For young readers

- Miller, William. Frederick Douglass: The Last Day of Slavery. Illus. by Cedric Lucas. Lee & Low Books, 1995. ISBN 1-880000-42-3

- Weidt, Maryann N. Voice of Freedom: a Story about Frederick Douglass. Illus. by Jeni Reeves. Lerner Publications, (2001). ISBN 1-57505-553-8

- Documentary films

- Frederick Douglass and the White Negro [videorecording] / Writer/Director John J Doherty, produced by Camel Productions, Ireland. Irish Film Board/TG4/BCI.; 2008

- Frederick Douglass [videorecording] / produced by Greystone Communications, Inc. for A&E Network ; executive producers, Craig Haffner and Donna E. Lusitana.; 1997

- Frederick Douglass: When the Lion Wrote History [videorecording] / a co-production of ROJA Productions and WETA-TV.

- Frederick Douglass, Abolitionist Editor [videorecording]/a production of Schlessinger Video Productions.

- Race to Freedom [videorecording] : the story of the underground railroad / an Atlantis

- The Frederick Douglass Papers Edition : A Critical Edition of Douglass' Complete Works, including speeches, autobiographies, letters, and other writings.

- Works by Frederick Douglass at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions illustrated)

- Works by Frederick Douglass at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Frederick Douglass at Online Books Page

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself.Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

- The Heroic Slave. From Autographs for Freedom, Ed. Julia Griffiths. Boston: John P. Jewett and Company. Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor, and Worthington. London: Low and Company., 1853.

- My Bondage and My Freedom. Part I. Life as a Slave. Part II. Life as a Freeman. New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855.

- Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape from Bondage, and His Complete History to the Present Time. Hartford, Conn.: Park Publishing Co., 1881.

- Frederick Douglass lecture on Haiti – Given at the World's Fair in Chicago, January 1893.

- Fourth of July Speech

- Letter to Thomas Auld (September 3, 1848)

- The Frederick Douglass Diary (1886-87)

- The Liberator Files, Items concerning Frederick Douglass from Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

- What to the Slave is the Fourth of July? July 5, 1852 EDSITEment Launchpad

- Video. In the Words of Frederick Douglass January 27, 2012.

- Frederick Douglass: Online Resources from the Library of Congress

- Frederick Douglass Project at the University of Rochester.

- Frederick Douglass (American Memory, Library of Congress) Includes timeline.

- Timeline of Frederick Douglass and family

- Timeline of "The Life of Frederick Douglass" – Features key political events

- Read more about Frederick Douglass

- Frederick Douglass NHS – Douglass' Life

- Frederick Douglass NHS – Cedar Hill National Park Service site

- Frederick Douglass Western New York Suffragists

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Frederick Douglass

- Mr. Lincoln's White House: Frederick Douglass

- Frederick Douglass at C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site The Washington, DC home of Frederick Douglass

- Frederick Douglass Gardens at Cedar Hill Frederick Douglass Gardens

- Frederick Douglass Circle in Harlem overlooking Central Park has a statue of Frederick Douglass. North of this point, 8th Avenue is referred to as Frederick Douglass Boulevard

- The Frederick Douglass Prize A national book prize

- Lewis N. Douglass as a Sergeant Major in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

- The short film Fighter for Freedom: The Frederick Douglass Story (1984) is available for free download at the Internet Archive[more]

- Combatants

- Theaters

- Campaigns

- Battles

- States

- Related topics

- Categories

From slavery to freedom

Douglass first tried to escape from Freeland, who had hired him out from his owner Colonel Lloyd, but was unsuccessful. In 1836, he tried to escape from his new owner Covey, but failed again. In 1837, Douglass met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman in Baltimore about five years older than he was. Her freedom strengthened his belief in the possibility of gaining his own freedom.[18]

On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped by boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. Dressed in a sailor's uniform, provided to him by Murray, who also gave him part of her savings to cover his travel costs, he carried identification papers which he had obtained from a free black seaman.[18][19][20] He crossed the Susquehanna River byferry at Havre de Grace, then continued by train to Wilmington, Delaware. From there he went by steamboat to "Quaker City" (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), and continued to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York; the whole journey took less than 24 hours.[21]

Frederick Douglass later wrote of his arrival in New York:

I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the 'quick round of blood,' I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: 'I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.' Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.[22]

Once Douglass had arrived, he sent for Murray to follow him to New York; she arrived with the necessary basics for them to set up a home. They were married on September 15, 1838, by a black Presbyterian minister eleven days after his arrival in New York.[18][21] At first, they adopted Johnson as their married name.[18]

Abolitionist activities

The couple settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts. After meeting and staying with Nathan and Mary Johnson, they adopted Douglass as their married name.[18] Douglass joined several organizations, including a black church, and regularly attended abolitionist meetings. He subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison's weekly journal The Liberator. In 1841 he first heard Garrison speak at a meeting of the Bristol Anti-Slavery Society. At one of these meetings, Douglass was unexpectedly invited to speak.

After he told his story, he was encouraged to become an anti-slavery lecturer. Douglass was inspired by Garrison and later stated that "no face and form ever impressed me with such sentiments [of the hatred of slavery] as did those of William Lloyd Garrison." Garrison was likewise impressed with Douglass and wrote of him in The Liberator. Several days later, Douglass delivered his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention in Nantucket. Then 23 years old, Douglass conquered his nervousness and gave an eloquent speech about his rough life as a slave.

In 1843, Douglass participated in the American Anti-Slavery Society's Hundred Conventions project, a six-month tour of meeting halls throughout the Eastern and Midwestern United States. During this tour, he was frequently accosted, and at a lecture in Pendleton, Indiana, was chased and beaten by an angry mob before being rescued by a local Quaker family, the Hardys. His hand was broken in the attack; it healed improperly and bothered him for the rest of his life.[23] A stone marker in Falls Park in the Pendleton Historic District commemorates this event.

Autobiography

Douglass' best-known work is his first autobiography Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, published in 1845. At the time, some skeptics questioned whether a black man could have produced such an eloquent piece of literature. The book received generally positive reviews and became an immediate bestseller. Within three years of its publication, it had been reprinted nine times with 11,000 copies circulating in the United States; it was also translated into French and Dutch and published in Europe.

Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime (and revised the third of these), each time expanding on the previous one. The 1845 Narrative, which was his biggest seller, was followed by My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855. In 1881, after the Civil War, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892.

Travels to Ireland and Britain

Douglass' friends and mentors feared that the publicity would draw the attention of his ex-owner, Hugh Auld, who might try to get his "property" back. They encouraged Douglass to tour Ireland, as many former slaves had done. Douglass set sail on the Cambria for Liverpoolon August 16, 1845, and arrived in Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine was beginning.

"Eleven days and a half gone and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle [Ireland]. I breathe, and lo! the chattel [slave] becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlour—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended... I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, 'We don't allow niggers in here!'" – fromMy Bondage and My Freedom.

He also met and befriended the Irish nationalist Daniel O'Connell[24] who was to prove to be a great inspiration.[25]

Douglass spent two years in Ireland and Britain, where he gave many lectures in churches and chapels. His draw was such that some facilities were "crowded to suffocation"; an example was his hugely popular London Reception Speech, which Douglass delivered atAlexander Fletcher's Finsbury Chapel in May 1846. Douglass remarked that in England he was treated not "as a color, but as a man."[26]

During this trip Douglass became legally free, as British supporters raised funds to purchase his freedom from his American owner Thomas Auld.[26] British sympathizers led by Ellen Richardson of Newcastle upon Tyne collected the money needed.[27] In 1846 Douglass met with Thomas Clarkson, one of the last living British abolitionists, who had persuaded Parliament to abolish slavery in Great Britain and its colonies.[28] Many tried to encourage Douglass to remain in England to be truly free of the fear of chains, but with three million of his black brethren in bondage in the US, he left England in spring of 1847.[26]

Return to the United States

After returning to the US, Douglass produced some abolitionist newspapers: The North Star, Frederick Douglass Weekly, Frederick Douglass' Paper, Douglass' Monthly and New National Era. The motto of The North Star was "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren." The abolitionist newspapers were mainly funded by supporters in England, who had sent him five hundred pounds to use as he chose.[26]

In September 1848, Douglass published a letter addressed to his former master, Thomas Auld, berating him for his conduct, and enquiring after members of his family still held by Auld.[29][30] In a graphic passage, Douglass asked Auld how he would feel if Douglass had come to take away his daughter Amanda as a slave, treating her the way he and members of his family had been treated by Auld.[29][30]

Women's rights

In 1848, Douglass was the only African American to attend the first women's rights convention, theSeneca Falls Convention.[31][32] Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution asking for women's suffrage.[33] Many of those present opposed the idea, including influential Quakers James and Lucretia Mott.[34] Douglass stood and spoke eloquently in favor; he said that he could not accept the right to vote as a black man if women could not also claim that right. He suggested that the world would be a better place if women were involved in the political sphere.

"In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world."[34]

Douglass refines his ideology

In 1851, Douglass merged the North Star with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party Paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper, which was published until 1860. Douglass came to agree with Smith and Lysander Spooner that the United States Constitution was an anti-slavery document.

This reversed his earlier agreement with William Lloyd Garrison that it was pro-slavery. Garrison had publicly expressed his opinion by burning copies of the document. Further contributing to their growing separation, Garrison was worried that the North Star competed with his own National Anti-Slavery Standard and Marius Robinson's Anti-Slavery Bugle. Douglass' change of position on the Constitution was one of the most notable incidents of the division in the abolitionist movement after the publication of Spooner's book The Unconstitutionality of Slavery in 1846. This shift in opinion, and other political differences, created a rift between Douglass and Garrison. Douglass further angered Garrison by saying that the Constitution could and should be used as an instrument in the fight against slavery.

On July 5, 1852, Douglass delivered an address to the Ladies of the Rochester Anti-Slavery Sewing Society, which eventually became known as "What to the slave is the 4th of July?" It was a blistering attack on the hypocrisy of the United States in general and the Christian church in particular.[36]

Douglass believed that education was the key for African Americans to improve their lives. For this reason, he was an early advocate for desegregation of schools. In the 1850s, he was especially outspoken in New York. The facilities and instruction for African-American children were vastly inferior. Douglass criticized the situation and called for court action to open all schools to all children. He stated that inclusion within the educational system was a more pressing need for African Americans than political issues such as suffrage.

Douglass was acquainted with the radical abolitionist John Brown, but disapproved of Brown's plan to start an armed slave rebellion in the South. Brown visited Douglass' home two months before he led the raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry. After the raid, Douglass fled for a time to Canada, fearing guilt by association and arrest as a co-conspirator. Douglass believed that the attack on federal property would enrage the American public. Douglass later shared a stage at a speaking engagement in Harpers Ferry with Andrew Hunter, the prosecutor who successfully convicted Brown.

In March 1860, Douglass' youngest daughter Annie died in Rochester, New York, while he was still in England. Douglass returned from England the following month. He took a route through Canada to avoid detection.

Civil War years

Before the Civil War

By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous black men in the country, known for his orations on the condition of the black race and on other issues such as women's rights. His eloquence gathered crowds at every location. His reception by leaders in England and Ireland added to his stature.

Fight for emancipation and suffrage

Douglass and the abolitionists argued that because the aim of the Civil War was to end slavery, African Americans should be allowed to engage in the fight for their freedom. Douglass publicized this view in his newspapers and several speeches. Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 on the treatment of black soldiers, and with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of black suffrage.

President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of all slaves in Confederate-held territory.[37] (Slaves in Union-held areas and Northern states would become freed with the adoption of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865.) Douglass described the spirit of those awaiting the proclamation: "We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky ... we were watching ... by the dim light of the stars for the dawn of a new day ... we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries."[38]

During the U.S. Presidential Election of 1864, Douglass supported John C. Frémont. Douglass was disappointed that President Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for black freedmen. Douglass believed that since African American men were fighting in the American Civil War, they deserved the right to vote.[39]

With the North no longer obliged to return slaves to their owners in the South, Douglass fought for equality for his people. He made plans with Lincoln to move the liberated slaves out of the South. During the war, Douglass helped the Union by serving as a recruiter for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. His son Frederick Douglass Jr. also served as a recruiter and his other son, Lewis Douglass, fought for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment at the Battle of Fort Wagner.

Slavery everywhere in the United States was outlawed by the post-war (1865) ratification of the 13th Amendment. The 14th Amendmentprovided for citizenship and equal protection under the law. The 15th Amendment protected all citizens from being discriminated against in voting because of race. Douglass' support for the 15th Amendment, which failed to give women the vote, led to a temporary estrangement between him and the women's rights movement.[40]

Lincoln's death

At the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington's Lincoln Park, Douglass was the keynote speaker for the dedication service on April 14, 1876. In his speech, Douglass spoke frankly about Lincoln, noting what he perceived as both the positive and negative attributes of the late President. He called Lincoln "the white man's president" and cited his tardiness in joining the cause of emancipation. He noted that Lincoln initially opposed the expansion of slavery but did not support its elimination. But Douglass also asked, "Can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see if Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word?"[41] At this speech he also said: "Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery...."

The crowd, roused by his speech, gave him a standing ovation. A long-told anecdote claims that the widow Mary Lincoln gave Lincoln's favorite walking stick to Douglass in appreciation. Lincoln's walking stick still rests in Douglass' house known as Cedar Hill.

In his last autobiography, The Life & Times of Frederick Douglass, Douglass referred to Lincoln as America's "greatest President."

Reconstruction era

After the Civil War, Douglass was appointed to several political positions. He served as president of the Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank; and as chargé d'affaires for the Dominican Republic. After two years, he resigned from his ambassadorship because of disagreements with U.S. government policy. In 1872, he moved to Washington, D.C., after his house on South Avenue in Rochester, New York, burned down; arson was suspected. Also lost was a complete issue of The North Star.

In 1868, Douglass supported the presidential campaign of Ulysses S. Grant. President Grant signed into law the Klan Act and the second and third Enforcement Acts. Grant used their provisions vigorously, suspending habeas corpus in South Carolina and sending troops there and into other states; under his leadership over 5,000 arrests were made and the Ku Klux Klan received a serious blow. Grant's vigor in disrupting the Klan made him unpopular among many whites, but Frederick Douglass praised him. An associate of Douglass wrote of Grant that African Americans "will ever cherish a grateful remembrance of his name, fame and great services."

In 1872, Douglass became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States, as Victoria Woodhull's running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket. He was nominated without his knowledge. During the campaign, he neither campaigned for the ticket nor acknowledged that he had been nominated.[8]

Douglass continued his speaking engagements. On the lecture circuit, he spoke at many colleges around the country during the Reconstruction era, including Bates College inLewiston, Maine, in 1873. He continued to emphasize the importance of voting rights and exercise of suffrage. In a speech delivered on November 15, 1867, Douglass said "A man's rights rest in three boxes. The ballot box, jury box and the cartridge box. Let no man be kept from the ballot box because of his color. Let no woman be kept from the ballot box because of her sex".[42][43]

In 1877, Douglass visited Thomas Auld, who was by then on his deathbed, and the two men reconciled. Douglass had met with Auld's daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, some years prior; she had requested the meeting and had subsequently attended and cheered one of Douglass' speeches. Her father told her she had done well in reaching out to Douglass. The visit appears to have brought closure to Douglass, although he received some criticism for making it.[29]

White insurgents had quickly arisen in the South after the war, organizing first as secret vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Through the years, armed insurgency took different forms, the last as powerful paramilitary groups such as the White League and the Red Shirtsduring the 1870s in the Deep South. They operated as "the military arm of the Democratic Party", turning out Republican officeholders and disrupting elections.[44] Their power continued to grow in the South; more than 10 years after the end of the war, Democrats regained political power in every state of the former Confederacy and began to reassert white supremacy. They enforced this by a combination of violence, late 19th-century laws imposing segregation and a concerted effort to disfranchise African Americans. From 1890–1908, Democrats passed new constitutions and statutes in the South that created requirements for voter registration and voting that effectively disfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites.[45] This disfranchisement and segregation was enforced for more than six decades into the 20th century.

Douglass' stump speech for 25 years after the end of the Civil War was to emphasize work to counter the racism that was then prevalent in unions.[46]

Family life

Douglass and Anna had five children: Rosetta Douglass, Lewis Henry Douglass, Frederick Douglass, Jr., Charles Remond Douglass, and Annie Douglass (died at the age of ten). Charles and Rossetta helped produce his newspapers. Anna Douglass remained a loyal supporter of her husband's public work, even though Douglass' relationships with Julia Griffiths and Ottilie Assing, two women he was professionally involved with, caused recurring speculation and scandals.[47]

In 1877, Douglass bought the family's final home in Washington D.C., on a hill above theAnacostia River. He and Anna named it Cedar Hill (also spelled CedarHill). They expanded the house from 14 to 21 rooms, and included a china closet. One year later, Douglass purchased adjoining lots and expanded the property to 15 acres (61,000 m²). The home has been designated the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. Anna Murray-Douglass died in 1882, leaving him with a sense of great loss and depression for a time. He found new meaning from working with activist Ida B. Wells.