Uhuru Sasa Shule and The East (Brooklyn)

In my youth I had the privilege & honor to experience some of what the all Black, Afro-Centric Schools & Summer Camps of Uhuru Sasa a part of a pan-African cultural center called The East which was based in Brooklyn, NY. This is where my undying love for my Black/African roots and people became a vital part of who I am to this day. Self pride as a Black is so important to me because of my experience with Uhuru Sasa... ~Malik ShabazzFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The East was a community education and arts organization in Brooklyn, New York focused on black nationalism founded in 1969.

Founding and Activities

Founded in 1969 in Brooklyn, New York by a group including students from the African American Student Association (ASA) and Jitu Weusi (Les Campbell), The East was a community education and arts organization based on principles of self-determination, nation building, and Black consciousness.[1][2] It served as a branch of Amiri Baraka’s Congress of African People (CAP)[3] until 1974, when The East pulled out of CAP due to CAP's ideological shift towards increased Marxism.[2]

Originally located at 10 Claver Place in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, The East served as a hive of many activities. It provided day care for children and evening classes for adults, and served as home for Black News, a bookstore, restaurant, catering service, food co-op, and a bi-weekly national Black nationalist news publication.[2][3] The East functioned as home to an independent African-centered school named Uhuru Sasa Shule (whose name translates to "Freedom Now" in Kiswahili, that emerged in response to the 1968 Ocean-Hill Brownsville school crisis.[4]

The East was also an important art center in Brooklyn, serving as a weekend jazz club, salon, and concert venue for Black musicians[2] and rivaling the popular clubs and theaters of Harlem.[1] It hosted performers including the Last Poets, Freddie Hubbard, Betty Carter, McCoy Tyner, Max Roach, Sun Ra, Lee Morgan, and Roy Ayers. Its name was included in the album title of Pharoah Sanders' "Live from the East."[3]

An offshoot of The East named Far-East was opened in Queens and, until 1974, hosted jazz, drama, dance, and poetry, as well as evening classes and a Uhuru Sasa preschool.[2] One major legacy of The East is its African Street Festival, now operating as an annual event in Bedford-Styuvesant known as the International African Arts Festival.[3]

See also

New York City teachers' strike of 1968

References

The Cambridge History of African American Literature. Graham, Maryemma., Ward, Jerry Washington. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. 2011. p. 433. ISBN 9780521872171. OCLC 527702733.

Kwasi., Konadu, (2009). A view from the East : black cultural nationalism and education in New York City. Brown, Scot, 1966-, Konadu, Kwasi. (2nd ed.). Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815632061. OCLC 759158744.

"Jitu Weusi Got Mad Soul | Black Star News". www.blackstarnews.com. Retrieved 2018-01-10.

Rickford, Russell. "“Our Nation Becoming”: Uhuru Sasa Shule and the Dual Power function of “Black Independent Institutions” in the Black Power Era." Dartmouth College: Avery Center Black Power Conference, 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2017 from http://avery.cofc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/rickford21.pdf

External links

https://www.mixcloud.com/OJBK/103-memories-of-the-east/

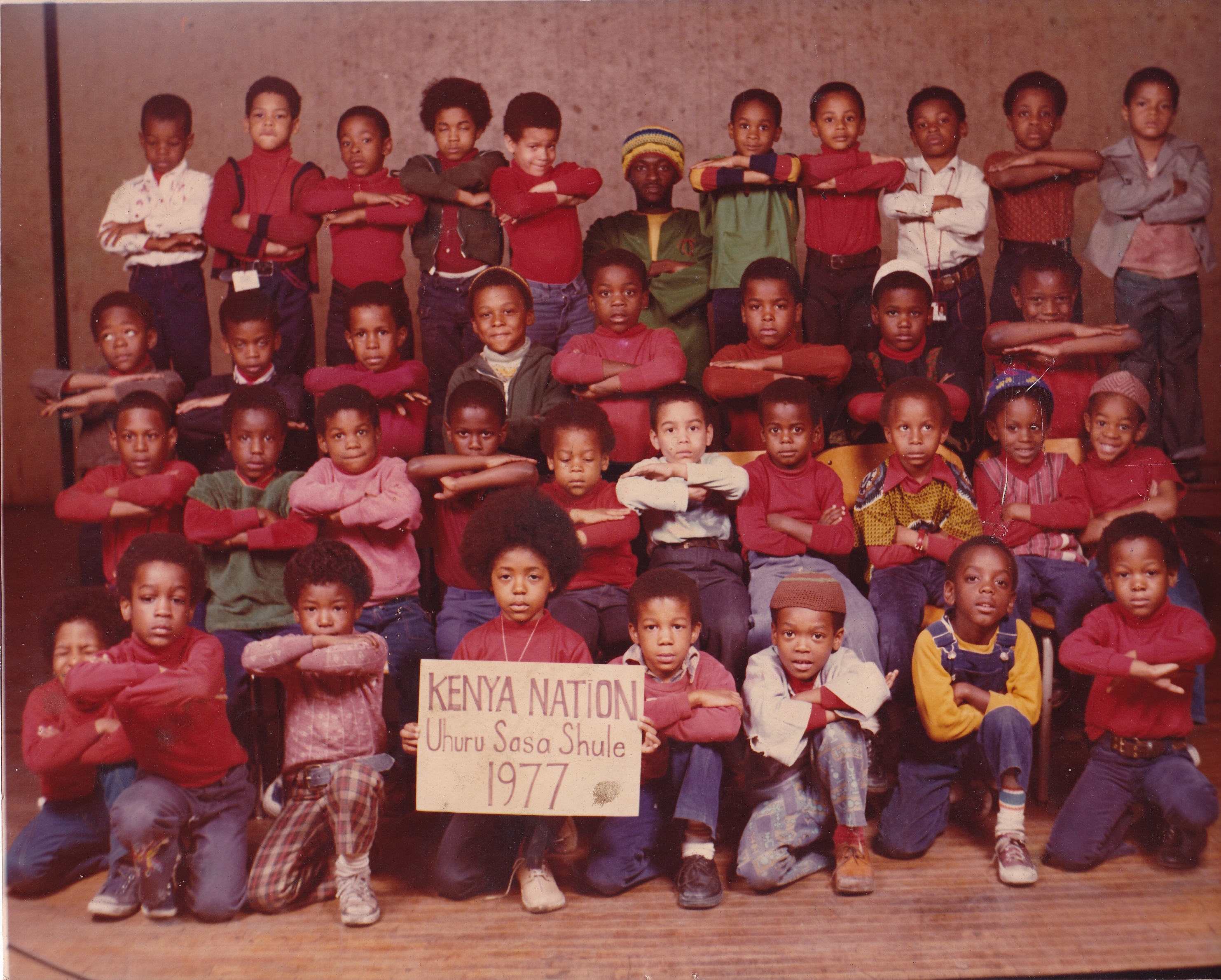

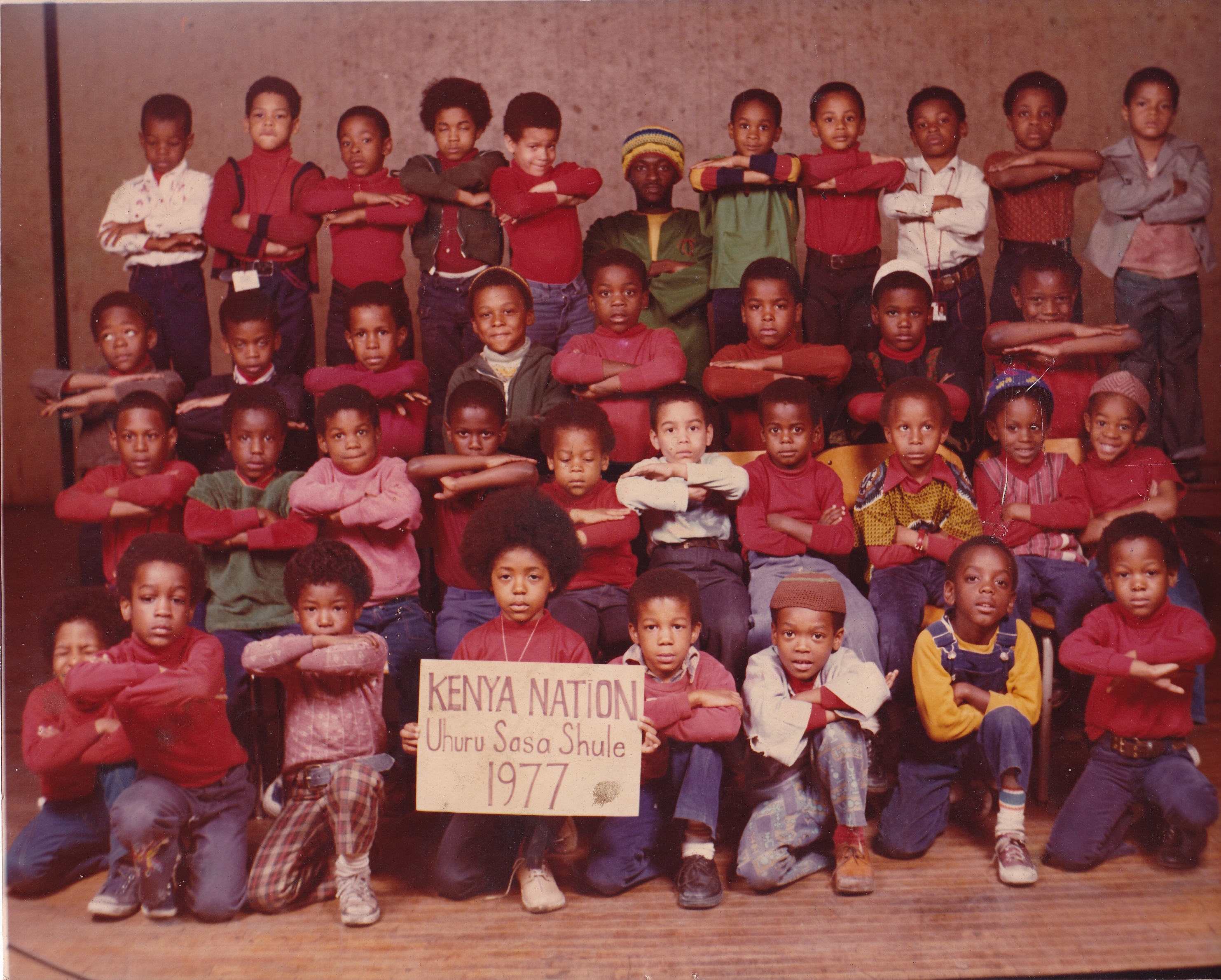

He’s been a lot of places, seen and done a lot of things, this 26-year-old Baraka Smith. All the proof is right here in his first apartment, a renovated flat in Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights. There is the huge wooden mask from Ghana he purchased on his second trip to Africa. The beautiful wall hanging of Chinese characters which translates into “peaceful mind, peaceful home,” from the nine months he studied in Taiwan. And then, over on the wall above his bookshelf, is the flimsily framed, aging class photo of 23 little brown boys in tight red turtlenecks.

“Oh, that?” he blushes. “Yeah, that was us. 1977. Uhuru Sasa Shule.”

Smith was seven years old then and in the equivalent of the second grade at Bedford-Stuyvesant’s Uhura Sasa Shule (“Freedom Now School” in Swahili). Yet to date, of all the different comings and goings in his relatively young life, attending Uhuru Sasa is the experience Smith says he remembers, cherishes and calls upon the most. “I am a teacher today because of what I witnessed,” he says. “The love, the discipline, and the real sense of community.”

While many adults say the memories of primary school years conjure warm feelings, for Smith those recollections also provide something else: rules to live by. “We knew that Uhuru Sasa meant ‘Freedom Now,’” adds Smith, who is now in his fifth year teaching seventh and eighth grade social studies at a public school, Brooklyn’s Satellite West Junior High School. “Even as kids, we knew we were each other’s keepers and that we were building a nation. We knew we were promoting the idea of self-determination.”

I see that look of surprise in your eyes yeah, yeah

I know you wonder yeah, yeah

from where that thunder

you see us now we’re black and we’re proud I said Uhuru Sasa

Freedom now, Freedom Now!

–Uhuru Sasa song

Founded in 1971, Smith’s prized school was also the first documented black, “Afrocentric” independent–that is to say, private–school in New York City. Its founders were a group of teachers who had taken leadership roles in the highly politicized Ocean-Hill Brownsville struggle for community empowerment in public education in the late 1960s.

In many ways, the realization of the dreams of Ocean-Hill Brownsville was not the 1971 decentra!ization plan that created 32 politically-connected community school boards to manage the city’s public schools; it was Uhuru Sasa. For those first parents and teachers, the school

provided true local control of curriculum, hiring, and every other element of their children’s education. And, inspired by the cultural nationalism of Kwanzaa architect and black studies pioneer Maulana Karenga, it was a solid move toward Afrikan~centered education and institution-building. Along with the school came a cultural organization, The East, which had under its umbrella a newspaper, a food co-op and a bookstore.

Over the following 13 years, Uhuru Sasa charted a trajectory away from the public school system until it closed its doors in 1984, a result of constant political and financial struggles.

“The institution folded,” says Uhuru Sasa founder Jitu Weusi, formerly known as Leslie Campbell. “But the concept and ideas put forth have never been extinguished.” In fact, what Uhuru Sasa left in its wake was a unique “how-to” model for high quality, cul-turally specific black independent education in New York City. And perhaps more important, say many who were affiliated with the school, the experiment proved black parents and their children did not have to be held hostage by the city’s notoriously poor pub-lic school system. Indeed, they had options.

Today, even as community control reaches its nadir in the public schools with last month’s return to near-total centralized authority, a new generation of black independent schools has become more popular than ever. There are nearly 80 of them in New York City, reports Dr. Gail Foster of the Toussaint Institute Fund, a New York-based nonprofit research organization that provides student scholarships to black independents. These institutions are recognized by the State of New York as qualified to formally teach and instruct children, yet they operate with complete autonomy. There are more than 400 similar schools nationwide.

The number of these schools has nearly doubled since 1984 and has been increasing steadily, according to the Washington-based Institute for Independent Education (lIE), another research organization that monitors school performance and assesses who chooses them and why. More and more black parents across the country are going the independent school route in an effort to avoid burdened and bureaucratic public school systems and to help build Afrocentric cultural understanding in the minds of their children, explains TIE director, Dr. Joan Davis Ratteray. Parents now have a broader choice of institutions than ever before, ranging .from nonsectarian schools to Christian academies. The schools themselves are generally small, with student populations ranging from as low as 50 to as high as 400.

This trend is, in many ways, a blast back to the past, says Dr. Ratteray. Until 1916, one of the few ways black people could get an education was to attend either church schools or schools that blacks them-selves had started. The earliest recorded example of a black independent school dates back to the 1790s, when Prince Hall, a black Revolutionary War veteran, decided he’d had enough of inferior schools for black children. “He was so incensed at how African children were mistreated, be started a separate school for them in his son’s basement,” Ratteray notes. “If you look at the cycles of integration and segregation in the country, you’ll find that whenever it’s gotten rough for our children, we’ve always pulled back into alternatives. It’s a wonderful legacy.”

_______

As the political and economic climate changes, how-ever, so does the spectrum of possibilities and problems for these institutions. Ironically, the question of options, which Uhuru Sasa set out to provide a living black answer to, is at the crux of the current school reform debate swirling around vouchers, charters and private versus public education. It’s the hot button that sends educators and administrators, conservatives and liberals into a frenzy. It touches home because it is a debate about money and power and, ultimately, the future of children.

And it is an extraordinarily complicated debate, one that divides even those who agree on the importance of black inde-pendent schools.

As former Uhuru Sasa administrator Adeyemi Bandele puts it, “There’s always going to be a linkage between public and private education in New York City. It was a public school’s African American teachers’ association that helped trigger the movement which became a black independent school.”

More than half a million black children in New York City attend public school. As a group, blacks are the largest single ethnic cohort in the city’s public school system, comprising nearly 40 percent of all the students. The problem is, many of them are performing at abysmally low levels. Nearly half of the special education population in the city is made up of black children. And citywide, only 43 percent of black students can read at grade level, compared to 70 percent of white students.

At one public school in Downtown Brooklyn, for instance, administrators report that nearly 30 percent of their third graders were held over last year. “Many of these children are reading much below grade level, if at all,” says the school’s assistant principal.

Academic experts blame social circumstances, racism and poverty for the racial disparity. But these are often exacerbated by other conditions. “One of the biggest problems is overcrowding,” says a Harlem public school teacher. “It’s no secret, but many of my students don’t even have books. Sometimes there are so many [stu-dents], it takes half the year to remember all their names.” Class sizes in many public schools are as high as 40 or more students in a room.

This is not the case at Brooklyn’s Cush Campus Schools on Kingston Avenue, its classrooms occupying the small study rooms of a former Jewish temple. Teachers here know the names of almost every student in the school. Founded in 1972, Cush Campus boasts a record of students routinely out-performing their counterparts in the public school system on state and standardized tests, says Principal Ora Abdur Ra.zzaq. One reason is that Cush, like other black independents, has an average class size of 15 or less. “We try to make sure that students here are at least two years ahead of where the public schools are,” she says.

Indeed, the 70,000 students who attend black independent schools across the country score 64 percent above the national norm for American students on standardized tests in math, and 62 percent better in reading, according to the TIE. New York mirrors the national figures.

_______

Ja! Le! Tu san ge!” A dozen children in a first and second grade class at Johnson Preparatory School on New York Avenue in Brooklyn, stand at attention and shout “Ready, set, go!” in Swahili at the top of their lungs before greeting their headmaster with a proud chorus of “Good afternoon, Mr. Akinyele and guest.”

Wearing a dark suit and round gold-wire spectacles, Nigerian-born Olusegun Akinyele is a stately and noticeably proper man. It is not at all surprising that, towering before the group of 5, 6, and 7-year-olds, he commands quite a presence. However, what has captured the hearts and minds of these students–as well as the 70 other students in kindergarten through eighth grade–has little to do with physical stature. “The teachers, they respect us,” explains eighth grader Karen Raghunanan. “And we respect them.”

The Johnson Preparatory School, formerly Weusi Shule (“Black School”), was founded over 23 years ago by a woman known as Queen Mother Ayanna Johnson. The school is housed in a small, two-story former doctor’s office. From the outside it is nondescript. But inside it is active, bustling and colorful.

“I remember the day before this school opened” in 1972, says kindergarten teacher “Sister” Natelege Conner. “Parents were on their hands and knees scraping and painting, doing anything necessary to get the school going.” Today, in Conner’s classroom, half of one wall is covered in big block letters with the school pledge, “We Are the Children of the Great Ancient Africans: We are the children of the Great Ancient Africans. We are an African People. We are brave. We are strong. We are beautiful and determined. We know no limits in education. We will continue to grow in strength and numbers and we will always love each other.”

On another wall hangs the red, black and green nationalist flag. On another, a poster that says Celebrate Africa. There are numbers and letters, too, as well as colors and shapes and sizes. But it is impossible to ignore the cultural messages that bombard the children throughout the day: love yourself, know your history. In an impromptu performance, the kindergarteners stand and excitedly recite a poem they performed at the school’s annual Kwanzaa production; it was titled Saga of the Afrikan Slave.

“This poem is also a reading lesson,” says Conner. “We have books where they practice writing it. For some of them I do dotted outlines of the letters.”

Immersing children in cultural messages and information alongside their academic instruction is central to Johnson Prep’s method, explains Headmaster Akinyele. In morning assemblies, for example, students sing both the black national and South African anthems. Akinyele says understanding the history and legacy behind these songs is a good civics lesson. Culture is not fluff, he insists, but instead the key to meaningful world citizenship. And he believes that for black children, these lessons must come from black people.

“We understand here, as controversial as this may seem, that it is not in the best interest of white people to teach our children. That’s the bottom line. Once you understand that, you understand also that this is not a luxury here. This is a crusade,” he says. “The [educational] philosophy is entirely nationalistic, African. Every thing is couched in [the premise] that if these children don’t know [their history] then nothing else you teach them matters. They walk away from us, even at these ages, almost fulfilled in terms of self. They know who they are. They know how not to let anyone else diminish their ego because someone else has a different skin color or hair texture.”

“That’s very necessary, especially at this level before they encounter the rest of the world. Because then, lies about you will not matter.”

Ratteray believes this philosophy works for many black parents “because social and cultural needs are very critical, and are often not being met elsewhere.”

Many black parents agree. “You can’t get away from the subtle to blatant racism shown to children in public schools,” says Gina Patrick, whose 6-year-old son, Shomari, is in the second grade at Johnson Prep. “II ranges from something as subtle as ‘fleshtone’ crayons to children not seeing themselves reflected anywhere–especially not in their teachers.”

Patrick represents a growing sentiment among black parents with school age children: a fear that their children will not thrive in public school environments. Though she is hardly wealthy, she is willing to pay approximately $355 a month for her son to be privately educated, and this year her daughter Salama will follow in his footsteps. “My son’s nickname is the Energizer Bunny because he has so much energy. If he were in public school, I know I would be fighting with the ‘Special Ed’ people because if he’s bored, you’re going to have a behavioral problem,” she says.

Akinyele believes large class sizes and a lack of academic rigor and discipline are the reasons why many children cannot succeed in public school. “If you’ve never taught just 12 people [in a classroom] then you don’t know the luxury. They can’t hide from me. There’s no sleeping in the class. When someone doesn’t understand something, you can tell immediately,” he says. “It’s remarkable. We’re teaching seventh and eigth grade classes like they were graduate seminars.”

“Rhetoric is the art of conversation,” says 13-year-old Karen Raghunanan.

“Logic is the art of thinking about how to think,” chimes in her friend and sixth grader Amanda Welch.

The girls are studying both topics in courses at Johnson Prep.

“We are challenging them to think,” says Akinyele. “When you have discipline, the sky itself is no limit. They can do anything and go anywhere. You show me a school that teaches people well and I’ll show you a school that has great discipline.”

For many educators, parents and students, these independent institutions are not only valid–they are the hope and cornerstone of a new black nation.

“These schools are part of a national movement to rebuild community infrastructures,” says Ratteray. Many of them are in some of the most blighted communities in the nation. In New York they can be found in struggling neighborhoods from Harlem to Bedford-Stuyvesant. Ratteray says they represent a self-determined revolution with a social, cultural and economic dimension. “You have to remember with these schools come 2,000 to 3,000 teachers, bus drivers, janitors and trustees. The [schools] provide jobs and training on one of the most important efforts. possible–how to run and maintain an institution. What better example for children to see?” she says.

_______

But black independent schools are not without their r fair share of problems, and children see and feel these as well, Financial problems plague many of the institutions. Unlike many mainstream white private schools that build large endowments and raise substantial foundation grant support, black schools survive almost solely on tuition income. “But that’s not enough,” admits Abdur Razzaq. “To do what we want to do with our children, we would need about $10,000 per child. Our communities cannot afford that.” Interestingly, $10,000 per year is at the low end of what many white private institutions cost; they often cost as much as $17,000.

As a result, there are compromises and concessions. “When you choose black independent schools, you know they might not have all the best things,” acknowledges Gina Patrick.

Patrick displays a pragmatism typical of the working class par-ents that traditionally send their children to these schools. According to TIE, the only organization to have done a compre-hensive analysis of families with children in black independents, the majority of these families have four to five members; 87 percent earn less than $49,000 a year; 57 percent earn less than $30,000; and a surprising 22 percent earn less than $15,000. Some of those at the low end receive scholarships, but because of funding constraints the amounts tend to be small.

“A lot of the people who say they can’t afford private school indeed can, it’s just not a priority for them. Many people pay more money for clothing and sneakers than parents [at this school] pay for tuition,” theorizes Akinyele, whose school offers a handful of scholarships to very poor children.

Jitu Weusi remembers that in the early days of Uhuru Sasa, no one was barred for inability to pay. But he adds, “We were also saddled with a deficit.” Currently, few if any of the schools will allow a student to simply not pay, but almost all of them work on sliding scale fees. “It’s a struggle. Our parents and teachers work very hard to keep this thing going,” says Akinyele.

Like most private schools, teachers at black independents often make significantly less than their counterparts at public schools. Isoke Nia, now a doctoral student at Columbia University’s Teachers College and a staff member at the Writing Project, a think tank and educator-training organization, was Baraka Smith’s teacher 20 years ago at Uhuru Sasa. “I think when

I started working there, I was making $55 a month and that $55 basically went to buy things in the classroom,” she recalls. Today, young teachers at black independents make as little as $16,000 a year, in some instances half as much as some first-year teachers make in the New York public schools.

_______

The debate about school reform and vouchers, more than the discussions about Afrocentrism, religion or academics, has proponents of the historically “do-for-self’ schools deeply divided. Those same activists and educators so much in agreement on

issues surrounding the fundamental need for black independent schools, fall on different sides of the school reform fence. The voucher proposal–an idea hailed by Governor George Pataki and other political conservatives–would allow parents to keep a certain amount of their tax dollars specifically to pay for the private education of their children. This would likely boost enrollment at black independents and would add to their revenue stream.

Thousands of public school teachers and other public school champions are virulently opposed to the idea–and, interestingly, some black independent school supporters agree with them. They argue that the deep class schisms that already characterize American education will be further exaggerated if vouchers come into play.

“Children in private schools are the ones that have support systems. They’re gonna make it anyway,” says Isoke Nia, explaining that the simple act of placing a child in an independent school indicates the parent is concerned about education–and is doing what it takes to help their child get ahead. The same is not always true for children from low-income families languishing in the worst public schools. “It’s the other ones we have to really worry about. I cannot tell you the degree of educational disparity money and parental action bring. I can take you fifteen minutes on the other side of the GW bridge and fifteen minutes to Long Island…. It’s unbelievable, the size of the classrooms, the materials. It’s vicious. If you don’t make noise, your children get nothing.”

Weusi, now a staff developer at Community School Board 23 in Brownsville, also suggests that the same communal concern behind the expansion of black independent schools should display itself in popular concern for the majority of black students still in the public school system. For these children, he says, vouchers will create a “very drastic situation.” The conservative political climate [will] wean monies from public education for private and parochials to better educate other children. Independent black schools are being used as the bait,” he charges. “Black schools have to realize the situation they’re in and not play into the hands of those who are trying to do away with public education, because those are our children.”

Ratteray from lIE calls such arguments “political shortsightedness.” She says that vouchers would improve the quality of independents, while forcing public schools to become more competitive and responsive. “Our children have been terribly ignored. Vouchers say why not let the parents take their tax money where they feel they can get a better education. Right now, poor parents are dealing with a monopoly.”

Besides, adds Akinyele, vouchers would give poor parents who really want to take their kids out of the public school system the boost they need to make it happen. “Public schools are not going anywhere, they’re going to be there,” he says. “Vouchers would help a few more people who thought they couldn’t afford private school find a way that they can.”

Black independent school administrators agree a major key to their success is the level of parental involvement. Nia, who has spent her career split between both worlds, says that if a voucher system were put in place, “you would have to do a serious education of parents. Essentially, vouchers are no more powerful than your voice, which, for too many parents, goes completely unheard.”

She and many of her colleagues argue that because so many parents are completely uninvolved in the education of their children now, they are no more likely to be involved if they had a voucher.

Mwalimu Shujaa, director of the Center for Independent Black Institutions, an organization started by teachers and administrators in the 1970s to promote Afrocentric schools, says he believes the voucher system would simply create another level of dependency. “We have to be clear,” he says bluntly. “These schools are about self-determination. We have to prove to the masses of people in the community that they are worth investing in.

_______

Mr. Baraka” as he is known to his 13- and 14-year-old students, says he really hasn’t give too much thought to the subject of vouchers. He teaches in public schools, yes. But, his heart, he admits, is with the independents. “I care about our children.

Attending Uhuru Sasa laid the foundation for my consciousness, where I learned the value of teaching your own. I mean, once, Mama Isoke brought the whole class of us home and we spent the night at her house, and played baseball at Prospect Park. At Sasa, your parents knew exactly who your teacher was and where she lived. We were family.”

Glancing across his living room at all those young faces in the 1977 class photo makes Baraka Smith smile. It’s like looking at an old family picture.

“The philosophy that I go by is rooted in my Sasa experience,” says Smith. “As a history teacher, I like my students to walk away with an understanding that history is today. And because of that, you have to realize the struggles of your ancestors. I’m never removed from my people. The fate of my people is my fate. My students know this. The fate of my family is mine.”

Many black nationalists replace the “c” in Africa with a in a symbolic effort to “reclaim” the continent.

dope... I'm the cat who wrote "Jitu Weusi, Got Mad Soul"... nuff respect!

ReplyDeletePeace!!!!

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI have a picture of my brother , Michael-Amonra with his class in 1977. He has passed this December 15, 2023 . Please get in contact with me

ReplyDelete