Frederick Douglass, original name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, (born February? 1818, Tuckahoe, Maryland, U.S.—died February 20, 1895, Washington, D.C.), African American who was one of the most eminent human rights leaders of the 19th century. His oratorical and literary brilliance thrust him into the forefront of the U.S. abolition movement, and he became the first black citizen to hold high rank in the U.S. government. WRITTEN BY: The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica LAST UPDATED: Feb 16, 2020 See Article History

Frederick Douglass’s Vision for a Reborn America

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, he dreamed of a pluralist utopia.

DAVID W. BLIGHT

DECEMBER 2019 ISSUE

“We are a country of all extremes, ends and opposites; the most conspicuous example of composite nationality in the world … In races we range all the way from black to white, with intermediate shades which, as in the apocalyptic vision, no man can name or number.”

— Frederick Douglass, 1869

In the late 1860s, Frederick Douglass, the fugitive slave turned prose poet of American democracy, toured the country spreading his most sanguine vision of a pluralist future of human equality in the recently re-United States. It is a vision worth revisiting at a time when the country seems once again to be a house divided over ethnicity and race, and over how to interpret our foundational creeds.

The Thirteenth Amendment (ending slavery) had been ratified, Congress had approved the Fourteenth Amendment (introducing birthright citizenship and the equal-protection clause), and Douglass was anticipating the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment (granting black men the right to vote) when he began delivering a speech titled “Our Composite Nationality” in 1869. He kept it in his oratorical repertoire at least through 1870. What the war-weary nation needed, he felt, was a powerful tribute to a cosmopolitan America—not just a repudiation of a divided and oppressive past but a commitment to a future union forged in emancipation and the Civil War. This nation would hold true to universal values and to the recognition that “a smile or a tear has no nationality. Joy and sorrow speak alike in all nations, and they above all the confusion of tongues proclaim the brotherhood of man.”

From December 1866: Frederick Douglass’s ‘Reconstruction’

Douglass, like many other former abolitionists, watched with high hopes as Radical Reconstruction gained traction in Washington, D.C., placing the ex–Confederate states under military rule and establishing civil and political rights for the formerly enslaved. The United States, he believed, had launched a new founding in the aftermath of the Civil War, and had begun to shape a new Constitution rooted in the three great amendments spawned by the war’s results. Practically overnight, Douglass even became a proponent of U.S. expansion to the Caribbean and elsewhere: Americans could now invent a nation whose egalitarian values were worth exporting to societies that were still either officially pro-slavery or riddled with inequality.

The aspiration that a postwar United States might slough off its own past identity as a pro-slavery nation and become the dream of millions who had been enslaved, as well as many of those who had freed them, was hardly a modest one. Underlying it was a hope that history itself had fundamentally shifted, aligning with a multiethnic, multiracial, multireligious country born of the war’s massive blood sacrifice. Somehow the tremendous resistance of the white South and former Confederates, which Douglass himself predicted would take ever more virulent forms, would be blunted. A vision of “composite” nationhood would prevail, separating Church and state, giving allegiance to a single new Constitution, federalizing the Bill of Rights, and spreading liberty more broadly than any civilization had ever attempted.

Was this a utopian vision, or was it grounded in a fledgling reality? That question, a version of which has never gone away, takes on an added dimension in the case of Douglass. One might well wonder how a man who, before and during the war, had delivered some of the most embittered attacks on American racism and hypocrisy ever heard could dare nurse the optimism evident from the very start of the speech. How could Douglass now believe that his reinvented country was, as he declared, “the most fortunate of nations” and “at the beginning of our ascent”?

From December 2018: Randall Kennedy on the confounding truth about Frederick Douglass

Few americans denounced the tyranny and tragedy at the heart of America’s institutions more fiercely than Douglass did in the first quarter century of his public life. In 1845, seven years after his escape to freedom, Douglass’s first autobiography was published to great acclaim, and he set off on an extraordinary 19-month trip to the British Isles, where he experienced a degree of equality unimaginable in America. Upon his return, in 1847, he let his profound ambivalence about the concepts of home and country be known. “I have no love for America, as such,” he announced in a speech he delivered that year. “I have no patriotism. I have no country.” Douglass let his righteous anger flow in metaphors of degradation, chains, and blood. “The institutions of this country do not know me, do not recognize me as a man,” he declared, “except as a piece of property.” All that attached him to his native land were his family and his deeply felt ties to the “three millions of my fellow-creatures, groaning beneath the iron rod … with … stripes upon their backs.” Such a country, Douglass said, he could not love. “I desire to see its overthrow as speedily as possible, and its Constitution shivered in a thousand fragments.”

Frederick Douglass, original name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, (born February? 1818, Tuckahoe, Maryland, U.S.—died February 20, 1895, Washington, D.C.), African American who was one of the most eminent human rights leaders of the 19th century. His oratorical and literary brilliance thrust him into the forefront of the U.S. abolition movement, and he became the first black citizen to hold high rank in the U.S. government.

Douglass was born in 1818, though the month and day are uncertain; he later opted to celebrate his birthday on February 14. Separated as an infant from his slave mother (he never knew his white father), Frederick lived with his grandmother on a Maryland plantation until he was eight years old, when his owner sent him to Baltimore to live as a house servant with the family of Hugh Auld, whose wife defied state law by teaching the boy to read. Auld, however, declared that learning would make him unfit for slavery, and Frederick was forced to continue his education surreptitiously with the aid of schoolboys in the street. Upon the death of his master, he was returned to the plantation as a field hand at 16. Later he was hired out in Baltimore as a ship caulker. Frederick tried to escape with three others in 1833, but the plot was discovered before they could get away. Five years later, however, he fled to New York City and then to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he worked as a labourer for three years, eluding slave hunters by changing his surname to Douglass.

An overview of the abolitionist movement in the United States, including a discussion of the Underground Railroad.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

See all videos for this article

At a Nantucket, Massachusetts, antislavery convention in 1841, Douglass was invited to describe his feelings and experiences under slavery. These extemporaneous remarks were so poignant and eloquent that he was unexpectedly catapulted into a new career as agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. From then on, despite heckling and mockery, insult, and violent personal attack, Douglass never flagged in his devotion to the abolitionist cause.

The Fugitive's Song

Cover illustration for The Fugitive's Song, a music score by Jesse Hutchinson, Jr., with “words composed and respectfully dedicated, in token of confident esteem, to Frederick Douglass,” 1845.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

To counter skeptics who doubted that such an articulate spokesman could ever have been a slave, Douglass felt impelled to write his autobiography in 1845, revised and completed in 1882 as Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Douglass’s account became a classic in American literature as well as a primary source about slavery from the bondman’s viewpoint. To avoid recapture by his former owner, whose name and location he had given in the narrative, Douglass left on a two-year speaking tour of Great Britain and Ireland. Abroad, Douglass helped to win many new friends for the abolition movement and to cement the bonds of humanitarian reform between the continents.

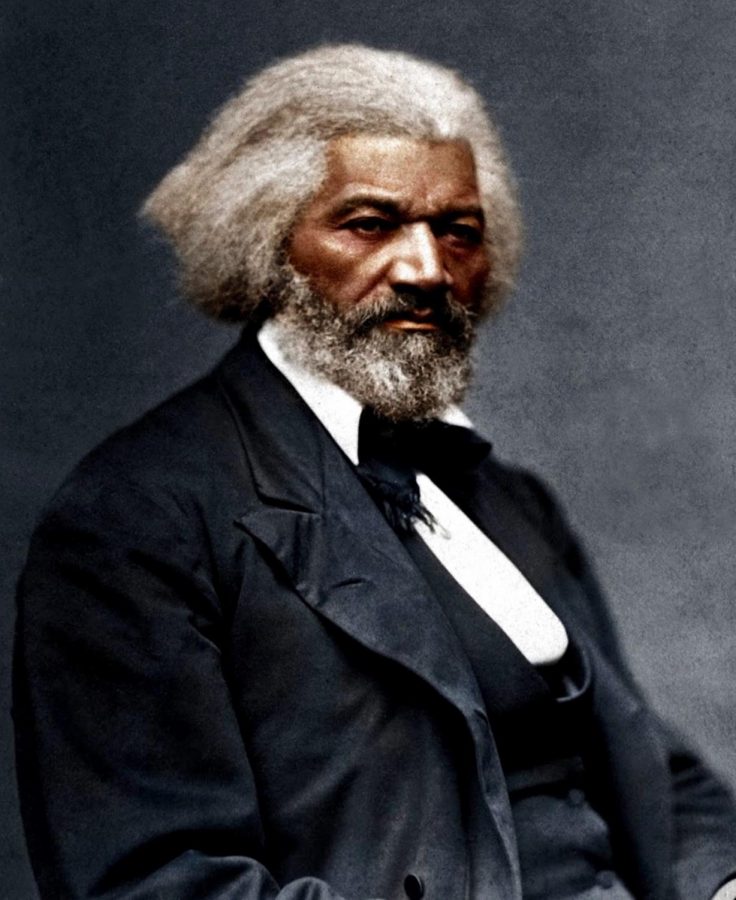

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Douglass returned with funds to purchase his freedom and also to start his own antislavery newspaper, the North Star (later Frederick Douglass’s Paper), which he published from 1847 to 1860 in Rochester, New York. The abolition leader William Lloyd Garrison disagreed with the need for a separate black-oriented press, and the two men broke over this issue as well as over Douglass’s support of political action to supplement moral suasion. Thus, after 1851 Douglass allied himself with the faction of the movement led by James G. Birney. He did not countenance violence, however, and specifically counseled against the raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia (October 1859).

During the Civil War (1861–65) Douglass became a consultant to Pres. Abraham Lincoln, advocating that former slaves be armed for the North and that the war be made a direct confrontation against slavery. Throughout Reconstruction (1865–77), he fought for full civil rights for freedmen and vigorously supported the women’s rights movement.

After Reconstruction, Douglass served as assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (1871), and in the District of Columbia he was marshal (1877–81) and recorder of deeds (1881–86). Finally, he was appointed U.S. minister and consul general to Haiti (1889–91).

No comments:

Post a Comment