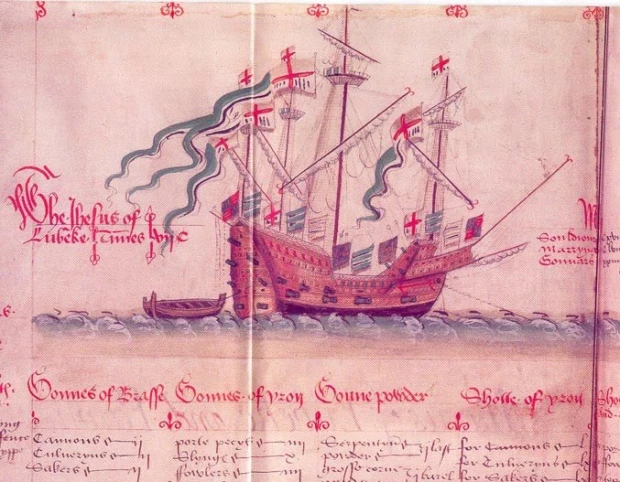

Jesus of Lubeck (Name of first Slave Ship to Grace the America’s.)

What has come to be referred to as “The Good Ship Jesus” was in fact the “Jesus of Lubeck,” a 700-ton ship purchased by King Henry VIII from the Hanseatic League, a merchant alliance between the cities of Hamburg and Lubeck in Germany. Twenty years after its purchase the ship, in disrepair, was lent to Sir John Hawkins by Queen Elizabeth.

Hawkins, a cousin of Sir Francis Drake, was granted permission from Queen Elizabeth for his first voyage in 1562. He was allowed to carry Africans to the Americas “with their own free consent” and he agreed to this condition. Hawkins had a reputation for being a religious man who required his crew to “serve God daily” and to love one another. Sir Francis Drake accompanied Hawkins on this voyage and subsequent others. Drake, was himself, devoutly religious. Services were held on board twice a day.

Off the coast of Africa, near Sierra Leone, Hawkins captured 300-500 slaves, mostly by plundering Portuguese ships, but also through violence and subterfuge promising Africans free land and riches in the new world. He sold most of the slaves in what is now known as the Dominican Republic. He returned home with a profit and ships laden with ivory, hides, and sugar. Thus began the slave trade.

Admiral John Hawkins is often remembered as one of the greatest men in the early English navy. Along with his cousin and companion Sir Francis Drake, he helped defeat the Spanish Armada and cement England’s role as ruler of the seas. But like most men who fell under the category of “Sea Dogs”, his career was filled with a blood-thirsty ruthlessness far removed from the modern ideas of heroes.

The Atlantic slave trade resulted in the enforced scattering of millions of Africans to the Caribbean, the Americas and elsewhere - including Britain. A significant early English figure was John Hawkins. His father, William Hawkins, made the first English expeditions to West Africa in the1530s. William Hawkins was an adventurous trader who set out to explore the Guinea coast. His voyages were made in search of commercial materials such as dyewoods.

Exploration and trade were the most significant reasons for people to move around the world during the 15th and early 16th centuries. The French, Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch sent their merchant seamen to Asia, Africa and the Americas, where trade developed rapidly. The English, anxious not to miss out on this bounty, became experts in shipping, finance and insurance and thus major players in overseas commerce.

From 1553, a group of London merchants began a series of ventures to develop English overseas trade. Two years later these adventurers returned carrying ivory, gold, Malaguetta pepper and, significantly, five Africans from Shama, in modern Ghana. These Africans were brought to England to learn English, and returned to Africa as interpreters for visiting English traders.

Queen Elizabeth I assisted the early merchant adventurers in 1561 by supplying ships and provisions. When they returned to English ports they brought not only valuable cargoes of commodities, but also more Africans, some of whom had probably become sailors on these merchant ships. Queen Elizabeth soon realised the economic value of this overseas trade. She granted a patent to eight merchants from London and Exeter to trade exclusively with Senegambia, between the Senegal and Gambia rivers, for a 10-year period.

European traders thus initially met Africans at a time long before colonial rule, when African societies possessed freedom of action and political power. As commercial trade and enslavement developed over the next 250 years, millions of Africans were transported from one continent to another. Some of those uprooted by the slave trade were also to end up in Britain - many as servants and labourers.

In 1562, John Hawkins set out on a voyage that would mark the beginning of the English slave trade. Documents reveal that he left Plymouth with the purpose of capturing Africans along the Guinea Coast. The travel writer Richard Hakluyt (c.1552-1616) says that Hawkins 'got into his possession partly by the sworde and partly by other meanes to the number of 300 negroes'. In Sierra Leone, he took a ship laden with ivory, wax and 500 Africans.

Hawkins, commanding the ship Salomon, then made the voyage from the Guinea coast to the West Indies. He arrived at the port of Monte Christi, in what is now the Dominican Republic, where they 'did deposit 125 slaves at 100 ducats each' (about £25-30 in present-day terms). The Africans were offered for sale to estate owners in the Americas, who required a constant supply of cheap labour for their sugar and tobacco plantations.

News of the slave merchants' success spread and they soon attracted wealthy, powerful backers, and additional support from Queen Elizabeth. In 1564 the queen sponsored Hawkins by lending him her very own 700-ton vessel, Jesus of Lubeck. Now John Hawkins, freeman of the city of Plymouth, left Plymouth specifically for the purpose of capturing Africans on the West African coast.

Hawkins, in his own words, as noted by Hakluyt, 'profited by the sale of slaves' - so much so that he included a bound slave wearing a necklace and earrings on the crest of his coat of arms. His final voyage turned out to be a disaster for Hawkins, as he lost his ships and men to the Spanish. This event precipitated hostilities between England and Spain.

References and Further Reading

Churchill, W., History of the English Speaking Peoples, vol. 4, London, 1956-8

File, N. and Power, C., Black Settlers in Britain 1555-1958, London, 1981

Fryer, P., Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain, London, 1984

Williamson, J. A., Sir John Hawkins: The Time and the Man, Oxford, 1927

This is a sketch for the arms and crest granted to John Hawkins, 'Canton geven by Rob[er]t Cooke Clar[enceux] King of Arms 1568'. The bound African slave on the crest reflects the trade that Hawkins pioneered.

from of The College of Arms, London (1568)

No comments:

Post a Comment