Holocaust Encyclopedia

The Nazi Party

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party—also known as the Nazi Party—was the far-right racist and antisemitic political party led by Adolf Hitler. The Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933. It controlled all aspects of German life and persecuted German Jews. Its power only ended when Germany lost World War II.

Key Facts

Introduction

The Nazi Party was the radical far-right movement and political party led by Adolf Hitler. Its formal name was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP). Nazi ideology was racist, nationalist, and anti-democratic. It was violently antisemitic and anti-Marxist.

The Nazi Party was founded in 1920, but won little popular support until the crisis of the Great Depression. In 1933, the German president appointed Hitler Chancellor. At the time, non-Nazis dominated Germany’s government. However, the Nazis used emergency decrees, violence, and intimidation to quickly seize control. The Nazis abolished all other political parties. They declared Germany a one-party state with Hitler as its supreme leader.

Origin of the Nazi Party

After World War I ended, Germany experienced great political turmoil. The Treaty of Versailles (1919) imposed harsh terms on Germany, which had lost the war. In addition, the country saw the overthrow of its monarchy. In its place was the new Weimar Republic, a democratic government. Racist and antisemitic groups sprang up on the radical right. They blamed Jews for Germany’s defeat in the war. These groups opposed the Weimar Republic and the Treaty of Versailles. They were against democracy, human rights, capitalism, socialism, and communism. They advocated to exclude from German life anyone who did not belong to the German Volk or race.

In September 1919, Hitler attended a meeting of one of these groups in Munich, the German Workers’ Party. This small political organization sought to convert German workers away from Marxist Socialism. At the meeting, Hitler’s public speaking skills attracted notice. He was recruited to a leading role.

In 1920, Hitler changed the Party’s name to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. “National Socialism” was a racist and antisemitic political theory. It had been developed in Hitler’s native Austria as the antithesis of Marxist Socialism and Communism. Marxists, for example, advocated for the global solidarity of the world’s workers. They called for the abolition of nation states. National Socialists, however, sought to unify members of the German Volk in complete obedience to the state. They called for a strong state to lead the “master race” in the “racial struggle” against “inferior races,” especially the Jews.

Hitler formulated a 25-point program in 1920. The program would remain the Party’s only platform. Among its points, it rejected the Versailles settlement. It also demanded to unify all people of German “blood.” The program called for a Greater Germany ruled by a strong central state. The country was to acquire new lands and colonies. The program would deny citizenship and rights to all non-Germans, particularly Jews.

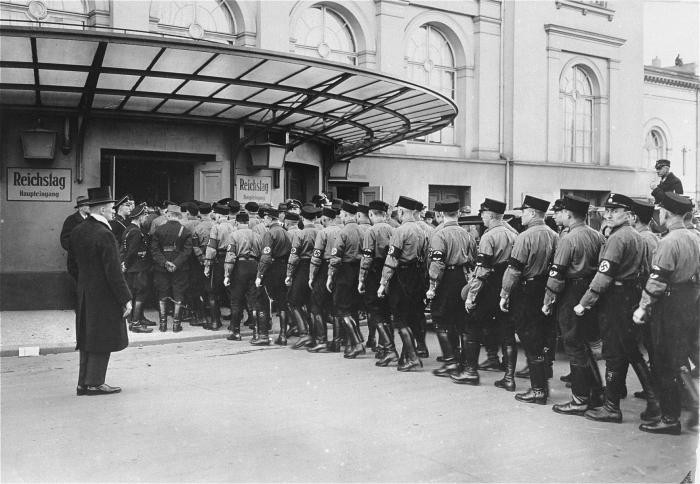

The Nazi Party grew steadily under Hitler’s leadership. It attracted support from influential people in the military, big business, and society. The Party also absorbed other radical right-wing groups. In 1921, Hitler organized a paramilitary force called the Storm Troops (Sturmabteilung, SA). SA members were war veterans and members of the Free Corps (Freikorps), paramilitary units that battled left-wing movements in postwar Germany.

The Beer Hall Putsch

On November 8–9, 1923, Hitler and his followers staged a failed attempt to seize control of the Bavarian state. They believed this would trigger a nationwide uprising against the Weimar Republic.

The uprising began in the Bürgerbräu Keller, a Munich beer hall. World War I hero General Erich Ludendorff, Hitler, and other Nazi leaders led the march. About 2,000 Nazis and sympathizers followed. City police clashed with the marchers, leading to an exchange of gunfire. Four police officers and 14 Nazis were killed. After the putsch, German authorities banned the Nazi Party. Several of its leaders were arrested and charged with high treason. Hitler was convicted in April 1924 and sentenced to five years in prison. He was released in December that same year.

While in prison, Hitler began dictating his book, Mein Kampf. The book set out his worldview and personal mission. Hitler believed he was destined to lead the German “master race” in the battle between races to control land and resources. He would achieve this by creating a racially pure state and conquering Lebensraum (living space) in the Soviet Union. Further, he would destroy the Germans' ultimate enemy, the Jews, and their most dangerous weapon: Judeo-Bolshevism. Mein Kampf was published after Hitler’s release. It did not become a bestseller in Germany until after he became Chancellor.

The Rise of the Nazi Party

After the putsch failed, Hitler concluded that the way to destroy the Weimar Republic was through democratic means. In 1925, he persuaded Bavaria’s leaders to lift the ban on the Nazi Party. Hitler promised that he would seek power only through elections. He then reestablished the Nazi Party under his complete control. What came to define the Party was not its 25-point program, but rather complete loyalty to its Führer or Leader, Hitler.

The Nazi Party prepared to stand in the elections. It organized branches in each German state. These branches worked to establish cadres in regions, cities, towns, and villages. The Nazi Party had a rigid top-down command structure. Officials were appointed from above rather than elected by members. In each region, a Gauleiter or District Leader served as head. This position was appointed by Hitler and answered directly to him.

The 1928 Reichstag Elections

The Nazi Party's membership had quadrupled by the 1928 elections for the Reichstag, Germany's parliament. However, it won only 2.6% of the votes and 12 seats.

Despite its name, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party won little support from industrial workers. This did not concern Hitler, who was seeking to create a mass movement. He aimed to appeal to the many groups that disliked the Weimar Republic and feared socialism and communism.

Hitler emphasized propaganda to attract attention and interest. He used press and posters to create stirring slogans. He displayed eye-catching emblems and uniforms. The Party staged many meetings, parades, and rallies. In addition, it created auxiliary organizations to appeal to specific groups. For example, there were groups for youth, women, teachers, and doctors. The Party became particularly popular with German youth and university students.

The 1930 Reichstag Elections

What most contributed to the Nazi Party’s success was Germany’s economic collapse during the Great Depression, beginning in 1929. The crisis resulted in widespread unemployment and poverty. It also led to an increase in crime. Germans’ resulting anger and fear left them vulnerable to arguments from the extreme right and left.

The 1930 elections saw a sharp rise in support for both the Nazis and the Communists. The Nazis had more support, though, winning 18.3% of the vote and 107 seats. With this outcome, they became the second largest party in the Reichstag. President Hindenburg and his conservative advisers did not want the largest party, the Socialists, to form a government and so tried to rule by presidential decree. They hoped in time to amend the constitution and establish authoritarian rule.

The 1932 Reichstag Elections

Increased political divide led to increased violence. The SA was especially violent. By 1932, it had amassed 400,000 members. That summer, there were deadly street battles and daily assassinations. More and more Germans came to agree with Hitler’s argument that parliamentary democracy was destroying Germany by catering to special interests. Hitler asserted that the nation needed a strong leader to unite Germany and rule in the national interest. The Party did not emphasize antisemitism in its general campaign messaging.

In the July 1932 elections, the Nazis became the largest party in the Reichstag. The Party had won 37.4% of the vote and 230 seats. Hitler, however, refused to join a coalition government unless he was appointed Chancellor. Hindenburg opposed this demand.

The Reichstag elections had to be held again in November 1932. The Nazi Party remained the largest party, but had won two million fewer votes than in July. The Party dropped to 196 seats, with 33.1% of the vote. By this time, Germany’s economy was on the mend and the Party’s popularity was receding. The odds for the Weimar Republic’s survival appeared to be improving.

Then, on January 30, 1933, Hindenburg appointed Hitler Chancellor in a coalition government. It was not dominated by Nazis, but rather by members of the conservative German National People’s Party and non-partisan professionals from the bureaucracy. Hindenburg took this step after his advisers assured him that the conservative members could control Hitler. They believed they could use Hitler’s mass following to amend the constitution and create an authoritarian state.

Germany becomes a one-party dictatorship under Hitler

Once he became Chancellor, Hitler moved quickly to bring the government under Party control. He persuaded Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag and announce new elections. The Nazis’ campaign platform called to unify all good Germans in the fight to eradicate “Marxism,” meaning both communism and socialism. The Nazi Party saturated Germany with its propaganda. Meanwhile, the government restricted the opposition press. In much of Germany, SA and SS (Schutzstaffel) members were deputized as auxiliary police. They used their powers to attack, arrest, and kill communists.

On February 27, 1933, there was a fire in the Reichstag building. The fire provided the excuse to declare a state of emergency. This allowed the government to abolish civil liberties and take over state governments. In the March 5 Reichstag elections, the Nazi Party won 44% of the vote. Together with its coalition partner, the Party barely won a majority of seats. Hitler used arrests, intimidation, and false promises to get the necessary votes to pass the Enabling Act on March 23. This “enabled” Hitler and his cabinet to dictate laws without approval from the Reichstag or President.

The Nazi Party did not only seize control of all levels of government. It also worked to control all aspects of German economic, social, and cultural life. This process was called Gleichschaltung, or "coordination." All other political parties were abolished by July 14, 1933. Germany was declared a one-party state under the Nazi Party. Government, legal, and educational institutions were purged of Jews and suspected political opponents. Workers, employers, writers, and artists came under control of Nazi organizations. Sports and leisure activities, too, fell under Nazi control. Only the military and the churches escaped “coordination.”

Threat from Within

By 1934, the main threat to Hitler’s continued control of the government came from within the Nazi Party, specifically the SA. SA men were eager to punish enemies and cash in on the Nazi takeover. Their violence and intimidation was met with increasing public disapproval. To reassure the nation, Hitler announced that the revolutionary phase of the “national uprising” had ended. Among the SA, however, there was talk of a second revolution. This was to be led by SA commander Ernst Röhm. By this time, the SA had 4.5 million members. It far outnumbered the Reichswehr, Germany’s armed forces. Röhm made no secret of his desire to subordinate the military to the SA. In June 1934, Germany's generals made clear to Hitler that he had to tame the SA or face a military coup.

On June 30, 1934, Hitler executed a bloody purge of the SA. The purge became known as the “Night of the Long Knives.” The estimated 150 to 200 victims included Röhm and other SA leaders, as well as conservative figures who had earned Nazi displeasure. Though subordinate to the SA, the SS carried out most of the murders. As reward, Hitler made the SS an independent Nazi organization. Its leader Heinrich Himmler answered directly to Hitler.

On August 2, 1934, President Hindenburg died. Every member of the German armed forces was then ordered to swear an oath of personal loyalty to Hitler. German military leaders had welcomed the slaughter of SA leadership. Without opposition, Hitler abolished the separate position of Reich President. He declared himself Führer and Reich Chancellor, the absolute ruler of the German people.

The Nazi Party in Power

All “Aryan” Germans were expected to participate in organizations run by the Nazi Party. However, the Party itself remained elite by limiting its membership. According to the “leadership principle,” it retained its top-down command structure. There were leaders at every level: regional, county, municipal, precinct, and neighborhood. Leaders were appointed from above and oversaw popular conformity to Nazi standards. Before it came to power, the Party had also created a government-like apparatus. Departments were responsible for the same areas as government ministries. For instance, there were departments for foreign policy, justice, labor, and economics. This structure never replaced the German bureaucracy. However, it acted alongside it and in continual competition with it.

Hitler transformed one party office into a government agency when he made propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels, head of the new Propaganda Ministry. Goebbels created a cult of personality that glorified Hitler as Germany’s infallible savior. Nazi propaganda became inescapable in Germany. It dominated the press, film, radio, and public spaces. Portraits or statues of Hitler appeared everywhere. Every city and town renamed a street or public space to honor him. In public, ordinary Germans were expected to praise Hitler and give the so-called German greeting ("Heil Hitler!"). Propaganda permeated school curricula as well. Children, for example, learned odes praising Hitler’s leadership in public schools. Leni Riefenstahl’s film “Triumph of the Will” vividly portrays the image of Hitler as an almost divine leader. The film is based on one of the Party’s massive rallies at Nuremberg.

The Nazi Party’s control of every level of government allowed it to pursue its antisemitic agenda. The central government enacted sweeping antisemitic decrees. Even before that, though, Nazi officials persecuted Jews at the local level. Jews were excluded from professions, businesses, and public spaces. Propaganda portrayed Jews as poisonous vermin plotting to destroy the German Volk through capitalism and bolshevism. Nazi leaders claimed that “the Jews” started World War II. The war was portrayed as a struggle for German survival. The Nazi claim that the Jews intended to destroy the Germans became the excuse for the Germans to destroy the Jews.

Defeat of Nazi Germany

By the late 1930s, the vast majority of Germans supported Hitler and the Nazi state. The only organized attempt to oust Hitler and the Nazi Party occurred on July 20, 1944. By this time, Germany’s defeat in World War II appeared inevitable. Following Hitler’s suicide on April 30, 1945, Germany surrendered and was occupied by Allied forces.

The Allies banned the Nazi Party and declared it a criminal organization. They tried top Nazi leaders for crimes against humanity, among other crimes. To this day, the Nazi Party is banned in Germany.